Is Real Estate a Good Inflation Hedge?

Real estate is often considered a good inflation hedge. Is it?

Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of considering real estate as an inflation hedge.

Arguments for real estate as an inflation hedge

These are the main arguments in favor of real estate as a source of inflation protection.

It’s a real asset

As a real, tangible asset, real estate is not entirely financial in nature.

While it shares qualities of being a financial asset since so much is typically bought on credit, land, houses, and infrastructure are physical, real things.

Real assets tend to do a reliable job of holding their value over time so long as they stay in demand.

Real estate is always going to be in demand because people need a place to live. The needs of commercial real estate change over time. For example, office space is now in less demand relative to data centers.

But when there is a limited supply of something and reliable demand over time, these types of assets tend to at least hold their value in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms.

For example, gold is a type of real asset that has held up well historically. Its supply is limited as only so much of it can be mined. And it functions as a reserve asset that has relatively stable demand.

And because governments around the world always want a positive inflation rate to avoid deflation, some of this money they create ends up going into stores of value like gold.

Gold, commodities, real estate, and stocks tend to benefit when there’s an easing of policy to get more money and credit into the system.

Real estate is an illiquid asset

Liquidity is important when it comes to the expected returns of an asset class. This holds for real estate as well.

It’s not as liquid as cash, bonds, or stocks. So for those looking to hold over longer time horizons, it can be a good inflation beater because this liquidity premium is priced into the market.

This lack of liquidity means that real estate prices aren’t marked to market like stock prices. The value still moves around, but you don’t see them given the private rather than public nature of most real estate investments.

The main effect of inflation is that it reduces the purchasing power of money.

So, if wages are rising in line with inflation, but the price of real estate is not, then real estate becomes relatively more affordable. Then it can become more of a “buyer’s market”, depending on credit conditions.

Likewise, if wages are going up in excess of inflation, then it might favor sellers, also depending on credit conditions.

Investors have it ingrained in their psychology that real estate does well when inflation is rising

Traders and investors tend to buy assets that they believe will go up in value as inflation accelerates.

Real estate is often thought of as one of these things. This is because real estate has a long-term track record of rising in value when adjusted for inflation.

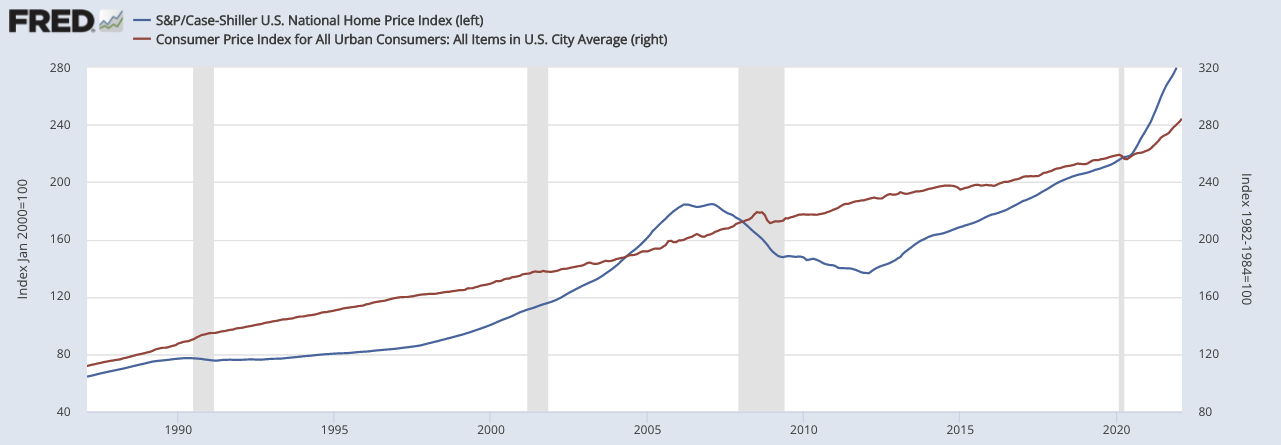

For example, in the US, the National Home Price Index (blue line) is compared to the CPI inflation rate (red line) from February 1987 (when both datasets have a common starting point).

National Home Price Index (blue) vs. CPI inflation rate (red)

(Sources: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

This thinking is not entirely wrong, but it’s important to remember that real estate doesn’t always go up in price. It’s just as likely to go down as any other asset when inflation is high.

For example, real estate prices fell in real terms during the stagflationary period of the 1970s when inflation was high and economic growth was low.

Investors need to be careful about extrapolating past performance into the future. Just because real estate did well in the past when inflation was high, doesn’t mean it will do well in the future.

An important long-run consideration is whether real estate is currently under or overvalued. This is a function of its price relative to its expected cash flow within a period.

Arguments against real estate as an inflation hedge

Real estate is a real asset, but it’s not always a good inflation hedge

Investors need to be careful about thinking of real estate as a surefire way to protect their purchasing power from inflation.

While real estate is a real asset, it doesn’t always hold its value in inflation-adjusted terms.

When real estate is undervalued, it can be a great inflation hedge. But when it’s overvalued, it can be a drag if and when the market corrects just like any other asset.

The financial and interest rate component of real estate

Real estate is typically purchased with lots of credit.

This gives the asset a very financial-like character.

When interest rates rise, real estate becomes less affordable because the lending part of it is more costly.

Inflation is a material part of what feeds into interest rates. If inflation rises, lenders will charge more to lend to offset the drop in their real returns.

So inflation, holding all else equal, can potentially make real estate prices fall, or at least take the wind out of a bull market in real estate.

So, it’s the interest rate risk that makes real estate only an okay inflation hedge.

This is a big reason why real estate prices fluctuate more than the prices of goods and services, as the chart above showed.

Lack of portability

Real estate can’t be transferred from place to place like various other types of assets.

So if there’s ever an issue in a particular region that makes the area less desirable, then it can hurt the investment irrespective of the inflation environment.

This is why real estate investors always need to be aware of the location risk they’re taking on. And these risks are not easy to ascertain.

It’s also worth noting that real estate is a very heterogeneous asset. There are all sorts of properties, from single-family homes to office buildings and everything in between in all sorts of different places in the world with different laws, regulations, and environments.

So, it’s important to not just think about real estate as one big asset class, but to consider the individual characteristics of each property before making an investment.

Better inflation hedge when it keeps pace with consumer prices

Real estate has a long history as a decent inflation hedge, but a lot of this is based on the idea that the income generated by buildings will tend to keep pace with consumer prices.

But not all investors appear to see property as defensive today.

US equity fund allocations to real estate, a guide for sentiment among professional money managers, have fallen.

Global allocations have also dipped.

On the other hand, inflows into listed real estate funds, a better proxy for attitudes among retail investors, are increasing.

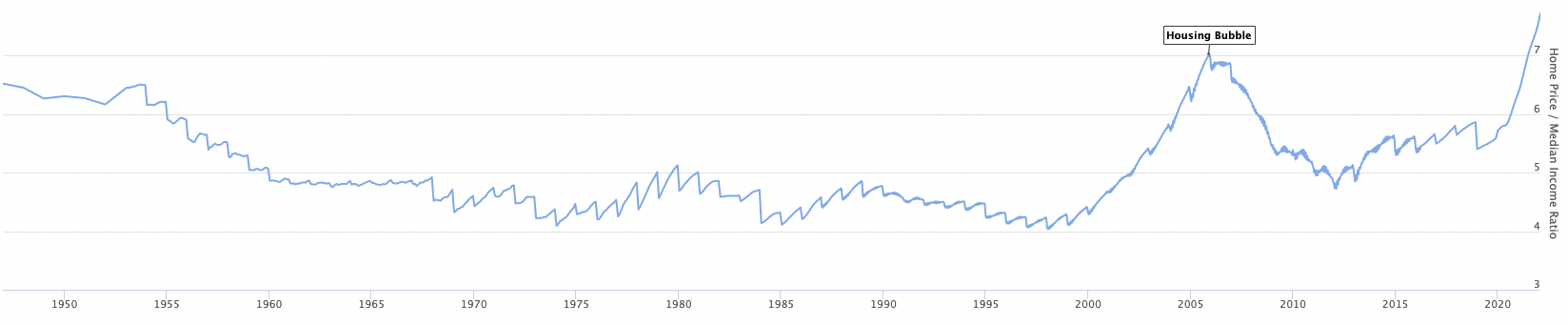

Home price-to-median income ratio

The home price-to-median income ratio in the US rose to 8x in 2022, the highest ever based on data that goes back 75 years.

During the housing bubble it peaked at 7x in 2006.

Home price / median income ratio (US)

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Longtermtrends)

Implications

This means with a 20 percent down payment, a 5.1 percent interest rate on a traditional 30-year mortgage, a person would be spending over 58 percent of their net income on a house.

At 50 percent down, 5.1 percent interest on a 30-year, they’d still be paying about 42 percent of their net on a house. These figures also ignore maintenance costs entirely.

This is getting into stretched territory where lenders won’t support underwriting these loans, so people’s tactics change.

People will then have to pay fees (“points”) to cut their interest rates and need to make higher down payments.

How far people are willing to extend forward their purchases also goes up. For example, people buying homes under construction are locking in today’s interest rates instead of risking that they’ll go up later.

Extended forward purchases is a classic bubble condition in all asset markets, especially in commodities and real estate.

Adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) applications also more than doubled in the first few months of 2022, so people can get lower rates in the earlier years of the loan.

The rate of change in appreciation in residential was already slowing in Q1 2022, which is natural given the lump of cash and credit distribution is over, as mentioned above.

This level of frothiness was true in all markets.

Stock valuations as a whole were high (at its peak, the 2020-2022 run got to about 70 percent of the way to the 1929 and 2000 bubbles).

Stock and bond wealth declined because interest rates rose faster than what had been discounted.

So, at 8x income, for a person to keep their housing costs within 25 percent of their net income, they would literally need to buy a home with 100 percent cash using the “one percent” rule for maintenance, as that would estimate 16 to 17 percent of their income wrapped up in the non-maintenance carry plus 8 percent of it toward routine repairs.

And to underscore the level of froth, 8x is just the median.

From March 2021 to March 2022, there had already been evidence of a slowing market:

- New home sales were down 12.6 percent in March compared with March 2021

- Existing homes sales were down by 4.5 percent year-over-year in March

- Pending sales (signed contracts that have yet to go to settlement) dropped by 8.2 percent in March

Interest rates impact everything

Interest rates impact how much house people can afford.

It also impacts borrowing rates relative to cap rates for property investors. If borrowing rates rise above cap rates, then cash flow is negative, at least in the beginning.

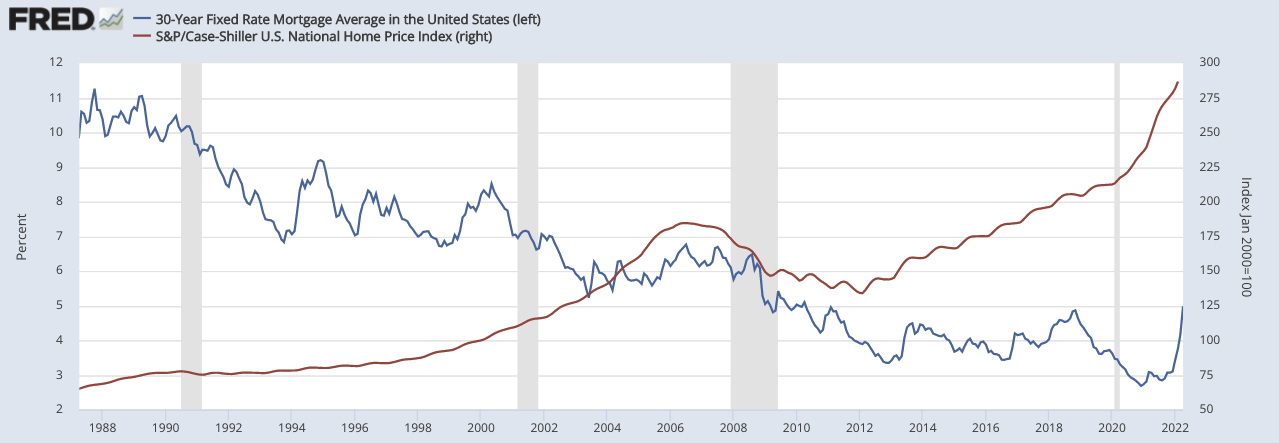

From 1981 to 2021, each cyclical peak and each cyclical trough in interest rates was lower than the one before it.

This provided a big tailwind to the prices of stocks, bonds, and real estate.

But when that changes, that is a material headwind to price increases going forward.

US home prices (red) vs. 30-year mortgage rates (blue)

(Sources: Freddie Mac; S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC)

The social and political impacts of housing inflation

Housing appreciated at a record pace during the early 2020s – even more and faster than the 2003-2007 housing bubble – generating more than $6 trillion in wealth for US homeowners.

This is a positive for Americans who own a home. But it’s also inseparable from the housing affordability crisis for those who don’t own a home.

The cumulative effects are likely to be sweeping and divergent.

This period of rising home equity will enable some families to create a form of intergenerational wealth for the first time.

But on the flip side of that, it will force other individuals and families to delay homeownership for years.

And because these gains were largely generated from the devaluation of money rather than a broad-based productivity boom, with some people benefiting while others finding home ownership even more unreachable, it can become a potential element of social conflict.

This, in turn, can feed into the types of policies voters might want to see in candidates and can potentially lead to bigger swings in the political pendulum.

Conclusion

Real estate can be a good inflation hedge, but it’s not without its risks.

Real estate is often bought with lots of credit, which makes it sensitive to interest rates and makes the asset class cyclical. Higher inflation typically leads to higher interest rates, which can dent demand for real estate, holding all else equal.

Moreover, investors need to be careful about extrapolating past performance into the future and should always be aware of the location and other risks involved with getting into the real estate market, whether through public (e.g., REITs) or private investments such as rental properties.