Pick Individual Stocks or Index? [What the Data Suggests]

Is it better to pick individual stocks or invest in index funds?

Stock picking vs. indexing has been a classic investment debate over the past few decades.

Mutual funds have been around for decades, providing broad exposure to lots of different stocks at a reasonable cost.

In the 1990s, ETFs became more popular, which are passive holdings of various stocks, bonds, and sometimes other exposures (e.g., commodities, currencies, crypto).

What the data says about picking individual stocks or indexing

Most of the return in the stock market over time comes from a few high-performing stocks rather than getting roughly comparable returns from everything.

Sometimes traders will look at indexes like the S&P 500 versus the equal-weighted S&P 500 to see how broad-based a rally is.

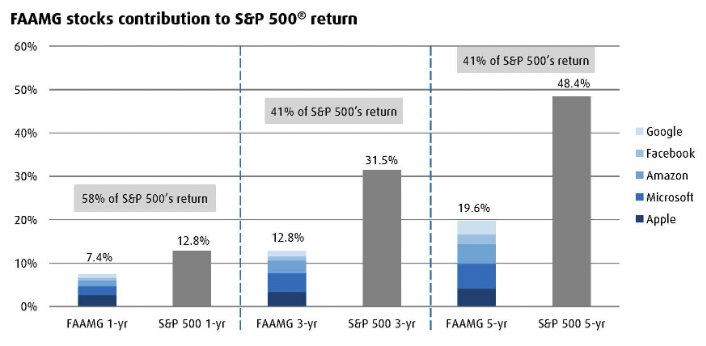

In the 2010s and into the 2020s, the S&P 500’s gains were heavily led by a smaller selection of companies like FAAMG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google).

The chart below shows FAAMG stocks’ contribution to the return of the S&P 500.

(Source: BMO Capital Markets)

It’s not uncommon, even among strong bull markets, to see that if you throw out the top few percent of stock-performers (on a trailing basis), the returns of the overall market are about nothing.

More than 95 percent of all stocks don’t outperform cash

Putting your money into the stock market is likely to make you money over the long run if you hold long enough.

However, more than 95 percent of all stocks, over their entire lifetimes as public companies, fail to outperform cash.

Most of an index’s gains over time is led by a handful of “superstocks” than the actual broad selection to choose from.

More than 50 percent of all stocks deliver negative returns

And more than half of all stocks deliver negative returns.

So while you’re likely to make money in the stock market as a whole, your chances of making money in any single stock aren’t as high as one would think.

What does all this mean?

The value of diversification

Diversification is not widely embraced.

For example, Mark Cuban, who made his first big sum of money selling Broadcast.com to Yahoo! near the peak of the dot-com bubble, said that diversification “is for idiots.”

Warren Buffett said:

If you are a professional and have confidence, then I would advocate lots of concentration. … If [investing is] your game, diversification doesn’t make sense. It’s crazy to put money into your 20th choice rather than your first choice.

After all, the more you put into the things that make you the most money, the better your portfolio will perform.

And you’re going to have a much better track record making a handful of bets you have confidence in rather than spreading yourself too thin.

However, when it comes to markets, that’s much easier said than done.

Even professional traders and investors have a lot of trouble outperforming an index.

Buffett has even said:

For everyone else, if it’s not your game, participate in total diversification. The economy will do fine over time. Make sure you don’t buy at the wrong price or the wrong time. That’s what most people should do – buy a cheap index fund, and slowly dollar-cost average into it.

Everything that’s already known is priced in

It’s important to note that everything that’s known is already discounted in the price.

Most everyone thinks that Google and Amazon are great companies. But they still trade at very high multiples relative to their earnings.

The Nifty Fifty of the late-1960s and 1970s were considered “can’t miss” stocks.

Yet they were very expensive and people who invested in them while they were hot ended up losing a lot of money.

Picking stocks is hard, and most people are better off indexing.

If you do pick stocks, it’s important to have an edge over everyone else. And that “everyone else” is sophisticated and there are a lot of smart people doing whatever they can to have an edge.

Because everything that’s known is already in the price this is how bad companies can compete with good companies.

When a bad company releases a really bad earnings report, its stock often goes up.

Why?

Because market participants expected an even worse earnings report and the “really bad” data point was better than discounted expectations, so it was bullish for the stock.

Likewise, a good company might release a really good earnings report and its stock might fall.

How can that happen?

Because investors expected an even better earnings report and they missed expectations.

So even if your entire portfolio is in one or a few great companies (e.g., Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft) that’s still a dangerous portfolio.

Those in employee stock ownership plans (ESOP)

Concentration can be especially dangerous for those in employee stock ownership plans, also known as ESOPs.

Companies tend to cut back their labor force when their stock price has fallen, either because of an economy- or market-wide issue or because the company itself has fallen on harder times and management is expected to do something to turn things around.

So employees can lose their job and see a cracked nest egg at the same time.

There are also infamous examples of disingenuous management teams encouraging employees to invest in the company’s stock as another lever to promote it even despite the company struggling behind the scenes.

In the case of Enron Corp, employees lost their jobs and the stock was eventually worth nothing despite the company being promoted by management (and most of the media) as a beacon of innovation with an underpriced stock.

Management themselves portrayed themselves as bigger-than-life characters.

Enron was a can’t miss stock of the dot-com era and did well even when the broader market struggled. It attracted a cult-like following of passionate fans.

Because the stock went up so much – it was at its peak America’s 7th-largest public company by market cap – this made people assume that the underlying narrative was legitimate.

The ultimate reinforcement for most people is price action. The more it goes up, the more they believe it must be okay.

Lots of people bought into the hype only to later find – if they didn’t cash in their gains and get out – that the company was little more than a stock promotion scheme and, in reality, a very mediocre company that lost money despite their financial statements purporting otherwise.

On the other hand, if a bad apple like this is only a small portion of one’s portfolio, these losses can be easier to tolerate.

So should you pick stocks or index?

It depends. If you have the skill, knowledge, and resources to find an edge, then stock picking can be a viable strategy.

Otherwise, it might be better to index.

Some can even do a hybrid of each – indexing for part of their portfolio and putting some amount into individual names.

And even if you do choose to pick stocks, remember that concentration is a double-edged sword.

It might give you the capacity to have higher highs. But it can also be dangerous. It’s important to diversify even if you have found a great company.

Things can always change no matter how much work has been put in. There are always things that will come along and essentially blindside you.

Dealing with what you don’t know is a very important part of trading and investing. And what you don’t know – and what you can’t know – is always going to be more than whatever it is that you can possibly know.

The market will always go against you for periods long than you hope. There’s the old saying that the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

This is especially true when it comes to stock picking. If you don’t have an edge, or if your edge starts to disappear, you can easily find yourself on the wrong side of a trade.

And if you’re not careful, you can end up losing everything.

Indexing and broader diversification can help you lower your risk without reducing your returns.