List of Contra-Currencies

Below we have a list of “contra-currencies.”

We pay a lot of attention to looking at whether our assets went up and down but much less attention to our currency risks.

Contra-currencies are assets or currencies that historically benefit relative to debasing fiat regimes.

They’re fundamentally contra-currencies because they’re scarce, externally anchored, or institutionally constrained.

This isn’t a list of “strong currencies” but a list of alternatives to policy-elastic money.

We also provide some commentary on portfolio strategy and how you might think of designing a portfolio allocation with this contra-currency list in mind.

Key Takeaways – List of Contra-Currencies

- Contra-currencies don’t need to rise in nominal terms. They need to lose less credibility than the unit being debased.

- In debasement cycles, attention turns away from strictly what our stocks, bonds, and other assets are doing. Money competition re-emerges. These are the competitors.

- A. Hard / Non-Elastic Monetary Assets

- Assets outside the fiat system by design. Limited or no supply elasticity.

- Gold – The archetypal contra-currency. No issuer, no liability, no policy committee. Performs when real rates fall, debt sustainability is questioned, and institutional trust erodes. Weak in Goldilocks growth periods with high real yields.

- Silver – A hybrid monetary-industrial metal. Tends to outperform gold in good economic environments when industrial demand is strong. Trades like a levered mix of gold and global PMI. Volatile and vulnerable in growth slowdowns. Generally ~75% correlated to gold. Doesn’t have gold’s diversification properties with its correlation to global credit cycles.

- Bitcoin – Algorithmically scarce (though not scarce in terms of other crypto available), portable, censorship-resistant. Functions as a hedge against capital controls rather than CPI inflation. Highly sensitive to global liquidity and leverage. Can correlate with high-beta risk assets.

- A1. Industrial-Heavy “Precious” & Strategic Metals

- Often mistaken for monetary hedges but dominated by credit and growth cycles.

- Platinum – Mostly industrial (autos, catalysts). Behaves like a credit-cycle metal. Underperforms in slowdowns unless supply shocks dominate.

- Palladium – Highly idiosyncratic industrial metal tied to auto cycles and substitution dynamics. Can spike on shortages but unreliable as a debasement hedge.

- Rhodium – Rhodium is an ultra-scarce, industrial metal. Demand is driven by auto and emissions demand (automotive catalytic converters are 80-85% of demand). Unlike gold’s monetary hedge or silver’s hybrid role, it’s volatile, illiquid, and tied to credit cycles.

- Copper – “Dr. Copper” reflation metal tied to electrification, construction, industrialization, and capex. Strong in reflation. Sells off early in credit contractions before debasement becomes visible. Good bellwether to economy.

- Nickel – Energy-transition metal with heavy China and policy sensitivity. Correlates strongly with global growth scares and supply-policy shifts.

- Aluminum – Broad industrial input linked to power prices and manufacturing. Performs in growth upswings. Trades like PMI beta in downturns.

- Zinc / Lead – Inventory- and construction-driven metals. Perform in expansions. Fragile in slowdowns. Poor money substitutes.

- A2. Energy & Strategic Scarcity Assets (Quasi-Monetary)

- Scarcity narratives dominate, but monetary linkage is indirect.

- Uranium – Often framed as a scarcity hedge, but driven by policy, regulation, and utility contracting cycles rather than debasement. Some geopolitical value too.

- Rare Earths (Basket) – Strategic and geopolitical assets. Opaque pricing, China policy risk, and subsidy-driven boom/bust dynamics. More geopolitics than monetary hedge.

- A3. Mixed “Monetary” Metal Baskets

- Blended real-asset exposures with declining purity as money substitutes.

- Gold + Silver + Select Metals Basket – Diversified real-asset sleeve. As industrial metals increase, exposure shifts from debasement hedge toward global growth and reflation beta.

- Commodity-Backed / Resource-Anchored FX

- Currencies whose value is implicitly tied to real production.

- Norwegian Krone (NOK) – Backed by energy exports and a sovereign wealth buffer. Fiscal discipline matters here.

- Canadian Dollar (CAD) – Energy, metals, and food exposure. Works best when global growth remains intact.

- Australian Dollar (AUD) – Industrial metals and Asia demand proxy. Cyclically volatile but resource-anchored.

- Chilean Peso (CLP) – Copper leverage. A niche contra-currency in commodity upcycles.

- External Surplus / Credibility FX

- Currencies supported by current account surpluses and domestic savings.

- Swiss Franc (CHF) – The classic “anti-political” currency. Benefits from capital flight and institutional trust.

- Singapore Dollar (SGD) – Managed but credibility-driven.

- Japanese Yen (JPY) – Paradoxical: heavily indebted, but domestically funded and tends to be reflexively safe in crises.

- Gold-Adjacency / Monetary Discipline Proxies

- Currencies with historical or behavioral linkage to sound money norms.

- Mexican Peso (MXN) – High carry + improving fiscal credibility. Functions as a relative contra-currency to worse offenders.

- Brazilian Real (BRL) – Volatile, but benefits when real rates are structurally positive versus debasing peers.

- Synthetic / Portfolio Contra-Currencies

- Not currencies per se, but functional money substitutes.

- Inflation-Linked Units (TIPS breakevens, CPI swaps) – Mechanical purchasing-power hedges.

- Commodity Baskets – Energy, metals, agriculture as a de facto currency when fiat loses signal value.

- Combining these in a portfolio? We cover portfolio strategy and an example portfolio at the end.

A. Hard / Non-Elastic Monetary Assets

These are outside the fiat system by design.

Gold

The archetypal contra-currency. No issuer, no liability, no policy committee. Performs when trust becomes a constraint.

Gold isn’t an inflation hedge in the narrow CPI sense; it’s a credibility hedge.

It responds less to current inflation prints and more to the trajectory of real rates, debt sustainability, and institutional trust.

Gold performs best when policymakers are trapped, unable to raise real rates without destabilizing the system.

Its strength is that it sits outside the credit system entirely, which is precisely why it underperforms during periods of growth optimism and policy confidence, and outperforms when those narratives break.

Gold can be inert in “Goldilocks” periods (strong growth, high real yields) and can lag risk assets early in reflations because it’s not a growth claim.

Silver

Gold with higher volatility and partial industrial linkage. It has historically tended to outperform late in inflationary cycles.

Silver behaves like a hybrid asset: part monetary metal, part industrial input.

This duality makes it inferior to gold early in debasement cycles but more explosive later, when inflation becomes broad-based and supply constraints matter.

Historically, silver outperforms gold in the later innings of monetary disorder, when speculative demand rises and confidence in paper assets weakens further. The trade-off is volatility. Silver is a levered expression of the same underlying forces.

Silver trades like a levered mix of gold + global PMI. In liquidity crunches or industrial slowdowns, it can sell off hard even if debasement risk is rising.

It’s a great late-cycle accelerant, but generally a poor early-cycle anchor.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin is algorithmically scarce, portable, censorship-resistant. Functions as a contra-currency when institutional trust erodes rather than when inflation rises.

It isn’t “digital gold” in behavior, but functions like a parallel monetary network.

Its value proposition activates when capital mobility, seizure risk, or monetary discretion become central concerns.

Bitcoin underperforms when liquidity is tightening, most notably.

It outperforms when debasement becomes overt, politicized, or enforced through controls. Those in emerging markets have viewed it as an alternative against institutional failure.

Bitcoin is highly sensitive to global liquidity and leverage in the financial system. In sharp tightening/risk-off phases it can correlate with high-beta tech, even if the long-run debasement thesis remains intact.

So, those are the three (gold, silver, and Bitcoin) are generally the most popular, and tend to be relatively accessible.

But there are others, so let’s look at them.

Platinum

Another precious metal that is mostly industrial (autos/catalysts, chemicals, jewelry).

Platinum is still a credit cycle metal.

It tends to weaken in global slowdowns and can underperform in stagflation unless supply shocks dominate.

It’s not a pure monetary hedge. It’s closer to a cyclical commodity with occasional scarcity spikes.

Let’s look at the correlations of the three most popular precious metals and to stocks.

Asset Correlations

| Name | Ticker | GLD | SLV | PPLT | SPY | Annualized Return | Daily Standard Deviation | Monthly Standard Deviation | Annualized Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPDR Gold Shares | GLD | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 8.64% | 1.00% | 4.55% | 15.77% |

| iShares Silver Trust | SLV | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 9.19% | 1.84% | 8.98% | 31.11% |

| abrdn Physical Platinum Shares ETF | PPLT | 0.55 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.41 | 1.36% | 1.53% | 6.60% | 22.86% |

| SPDR S&P 500 ETF | SPY | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 14.37% | 1.08% | 4.13% | 14.32% |

| Asset correlations for time period 02/01/2010 – 12/31/2025 based on monthly returns | |||||||||

Gold is strongly correlated with silver (+0.76) and moderately with platinum (+0.55). This shows their shared precious-metal dynamics.

Silver and platinum are even more closely linked (+0.70) because of their heavier industrial and cyclical exposure.

Correlation to equities (S&P 500) rises as metals become more industrial: gold is nearly uncorrelated with stocks (0.08), silver modestly so (0.28), and platinum more meaningfully correlated (0.41).

The takeaway: gold behaves as a monetary hedge, while silver and especially platinum increasingly track global growth and risk assets.

Palladium

Even more concentrated industrial demand (catalysts).

Palladium is extremely idiosyncratic, driven by auto cycles, substitution to platinum, and supply constraints.

It can rip higher on shortages, but it’s not reliably tied to debasement, more to micro supply/demand and global manufacturing.

Rhodium

Rhodium is a poor store of value despite extreme scarcity.

Its price is dominated by automotive emissions demand, regulatory shifts, and supply shocks, not monetary conditions.

Roughly 80-85% of rhodium demand comes from automotive catalytic converters (emissions control), with most of the remainder from chemicals, glass, and electronics.

It lacks liquidity, financialization, and investment infrastructure, which makes it highly volatile and cyclical.

Unlike gold or even silver, rhodium isn’t a great candidate for preserving purchasing power across cycles.

It functions as a speculative industrial metal, not a monetary hedge.

As such, it has very little investment demand compared with gold or silver.

Copper

The “Dr. Copper” macro metal: electrification + construction + global capex.

Copper is an excellent hedge against reflation and infrastructure spending, but it’s pro-cyclical.

In credit contractions it can fall sharply, often before debasement becomes obvious, because demand destruction hits first.

Nickel

Nickel is an energy transition metal (batteries, stainless steel).

Highly cyclical and policy-sensitive (Indonesia supply dynamics, battery tech shifts). It can correlate strongly with China credit impulses and global growth scares.

Aluminum

Broad industrial input with strong linkage to power prices.

Performs in reflation.

In downturns it trades like global manufacturing beta.

Also vulnerable to demand shocks and inventory cycles.

Zinc / Lead

Construction/galvanizing (zinc) and batteries (lead).

Classic inventory/PMI metals: good in growth upswings, fragile in slowdowns.

Not reliable as “money substitutes.”

Uranium

Uranium is often marketed as scarcity hedge tied to energy security.

It’s dominated by policy/regulatory cycles and contracting dynamics (utilities), not monetary debasement.

It can boom in supply squeezes and still be orthogonal to inflation hedging.

Rare Earths (basket)

Rare earths are strategic materials with geopolitical optionality.

Hard to own cleanly, opaque pricing, heavy China policy risk, and prone to boom/bust driven by subsidies and stockpiling, so more geopolitics than debasement.

“Monetary” baskets (gold + silver + select metals)

Useful as a diversified real-asset sleeve.

The more you add industrial metals, the more your “contra-currency” becomes a global growth trade – great in reflation, weaker in crises.

Other high niche metals

There are other metals with economic value that are rarely talked about for market/investment/trading purposes.

We’ll leave these here as a type of “other” category:

- Iridium – Ultra-scarce platinum group metal (PGM). Electronics/chemicals demand. Illiquid and supply-shock driven. Not a debasement hedge.

- Ruthenium – Niche industrial PGM (electronics/chemicals). Opaque pricing and low investability.

- Osmium – Extremely rare with a tiny market. Collectible-like, poor liquidity.

- Cobalt – Battery/geopolitics metal. Volatile, policy-sensitive. China/DRC supply risk.

Especially with metals like ruthenium and osmium, they are so niche that they lack standardized daily spot quotes like precious metals.

Price estimates will need to come from industry assessments and any limited market references.

Practical macro rules

- Gold is the closest thing to a true contra-currency.

- The moment you move toward silver/platinum/copper, you gain upside in reflation but inherit credit-cycle correlation.

- So build it as a barbell: gold (credibility hedge) + selective cyclicals (reflation beta), rather than pretending everything “metal” is money.

B. Commodity-Backed / Resource-Anchored FX

Commodity FX work when debasement raises real goods prices and fail when demand collapses or politics intrude.

So they’re currencies whose value is implicitly tied to real production.

Commodity-backed currencies function as contra-currencies not because they are immune to debasement, but because their terms of trade impose real-world constraints.

You can’t print oil, copper, iron ore, or wheat.

When global money supply expands faster than real goods, producers of those goods gain relative pricing power.

These currencies tend to outperform in early-to-mid debasement, when inflation is transmitted through commodity prices rather than financial repression.

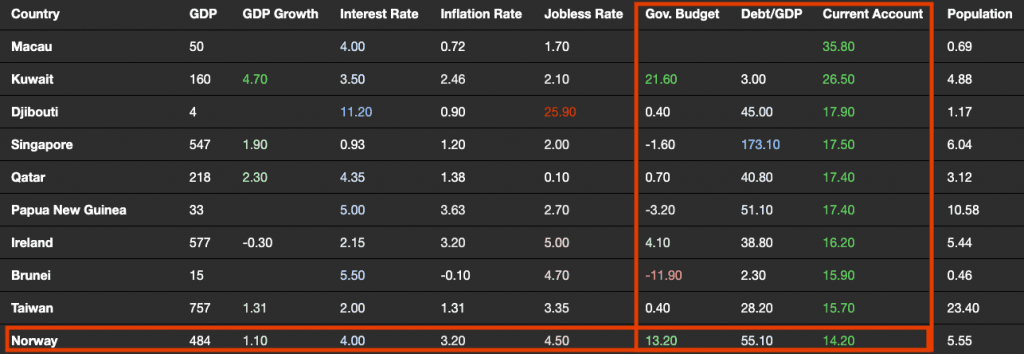

Norwegian Krone (NOK) – Backed by energy exports and a sovereign wealth buffer

The krone is a textbook example of a resource currency reinforced by institutional design.

Energy exports anchor external balances, while the sovereign wealth fund sterilizes windfalls and dampens procyclicality.

This matters: debasement elsewhere shows up as higher real purchasing power here only if fiscal discipline is maintained.

NOK underperforms when energy prices fall or when global growth weakens.

At the same time, it remains structurally advantaged relative to heavily indebted importers during inflationary regimes.

We can see Norway’s government budget and current account as both in surplus.

Canadian Dollar (CAD) – Energy, metals, and food exposure; works best when global growth remains intact

CAD is a diversified commodity currency rather than a single-commodity play.

Energy dominates at the margin, but agriculture and metals broaden the base to some extent.

This makes CAD strong during reflation and early debasement phases, especially when North American growth is stable.

Its weakness is sensitivity to global slowdowns.

When demand falls, commodity currencies lose their anchor.

Australian Dollar (AUD) – Industrial metals and Asia demand proxy; cyclically volatile but resource-anchored

AUD is best understood as a levered expression of global industrial cycles.

Iron ore and coal tie it directly to infrastructure spending and Asian demand, particularly China.

In debasement regimes driven by stimulus and fixed-asset investment, AUD can outperform sharply.

Its volatility is structural: AUD sells off quickly when global liquidity tightens or when commodity demand slows.

Chilean Peso (CLP) – A niche contra-currency in commodity upcycles (especially copper)

CLP is heavily a single-factor currency: copper.

CLP benefits disproportionately from copper shortages, but suffers from political risk and limited monetary credibility.

It’s a niche instrument for specific macro views, not a core reserve alternative.

C. External Surplus / Credibility FX

External surplus currencies hedge policy excess.

These are currencies supported by strong current account surpluses and domestic savings.

These currencies act as contra-currencies not because they’re tied to physical assets, but because they are anchored in behavioral restraint.

Savings surpluses, conservative institutions, and political aversion to inflation create currencies that debase more slowly – and more predictably.

In debasement regimes, predictability itself becomes valuable.

Swiss Franc (CHF) – The classic “anti-political” currency; benefits from capital flight and institutional trust

The Swiss franc is less a growth currency than a trust repository.

Its strength comes from institutional continuity, political neutrality, and a long-standing social preference for price stability over short-term stimulus.

Capital flows into CHF during periods of geopolitical stress, financial instability, or policy overreach elsewhere.

Ironically, its primary weakness is its own success: excessive inflows force intervention.

The SNB (their central bank) has been known to buy foreign equities to prevent its currency from becoming too strong.

Still, CHF functions as a contra-currency because it represents an opt-out from global political risk rather than a bet on economic expansion.

Singapore Dollar (SGD) – Managed but credibility-driven; prioritizes purchasing power over growth optics

SGD is one of the clearest examples of deliberate monetary credibility.

Unlike most fiat regimes, policy is explicitly oriented toward preserving purchasing power rather than maximizing growth or asset prices.

The currency is actively managed against a basket, but that management is rules-based and transparent.

The “rules” refer to the Basket, Band, and Crawl (BBC) framework used by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) – their central bank.

Unlike central banks that set interest rates (like the Fed), Singapore sets a “path” for its currency value to ensure stability.

The MAS manages the Singapore Dollar Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (S$NEER) against a trade-weighted basket of currencies.

They don’t reveal the exact weights of the basket or the exact limits of the band. But they transparently announce how they’re adjusting these three “rules” (levers):

The Slope (The Crawl) is the primary means for managing inflation. The MAS sets a specific rate at which the currency band rises (appreciates) over time.

For example, if relative interest rates are supporting capital inflows, they steepen the slope. This causes the SGD to strengthen faster against trade partners, which makes imports cheaper and cools prices.

The Width (The Band) defines how much the currency is allowed to fluctuate around the target path. This prevents the MAS from micromanaging a specific level.

So if the global economy is more volatile or uncertain, they widen the band to allow the currency to absorb shocks without requiring the immediate intervention.

The Center (The Level) is the midpoint of the band.

Japanese Yen (JPY) – Paradoxical: heavily indebted, but domestically funded and reflexively safe in crises

JPY appears contradictory: massive public debt, persistent monetary easing, and yet repeated safe-haven behavior.

Why?

The general explanation lies in ownership and funding structure.

Debt is domestically held, savings are deep, and foreign liabilities are limited.

In global risk-off events, the narrative is that capital can be repatriated, strengthening the yen regardless of fundamentals.

Nonetheless, JPY’s contra-currency status is cyclical rather than structural.

It protects during crises. But it’s vulnerable during prolonged inflationary regimes where domestic repression intensifies.

We took a look at the yen’s changing safe-haven status here.

What we found is that Japan’s “safe haven” behavior is because global risk-off triggers short-covering and funding stress: leveraged positions funded in JPY get unwound, forcing JPY buying in spot/derivatives.

At the same time, Japan’s domestic-funded balance sheet limits forced foreign-currency funding squeezes, so JPY tends to rise when global balance sheets delever.

For example, when global investors are forced to delever during a crisis, countries with large foreign-currency debts must sell their currency to raise dollars, while Japan doesn’t. So instead, JPY funding positions are unwound and the yen is bought, which in turn will push it higher.

Gold-Adjacency / Monetary Discipline Proxies

Gold-adjacency currencies hedge relative discipline, not absolute debasement.

They work when the global problem is “too much money everywhere,” but some policymakers still choose restraint.

In debasement regimes, the winners often aren’t the purest systems, but the least compromised ones.

You’ll often hear the phrase “cleanest dirty shirt” because many have analogous problems.

So what we’re talking about here are currencies with historical or behavioral linkage to sound money norms.

These currencies aren’t hard money, nor are they anchored to commodities or largepersistent surpluses.

Their contra-currency status is relative and behavioral.

They benefit when policymakers choose discipline. This could come in the form of high real rates, orthodox policy frameworks (i.e., not what Turkey does), and credibility – in a world where others won’t/can’t. (Related: FX Valuation Models)

In debasement cycles, relative restraint matters almost as much as absolute soundness.

Mexican Peso (MXN) – High carry + improving fiscal credibility; functions as a relative contra-currency to worse offenders.

Mexico has cultivated a reputation for conservative fiscal management, central bank independence, and inflation aversion (by EM standards).

High nominal and real rates attract carry flows, and improving credibility reduces tail risk.

MXN isn’t a great hedge against global inflation shocks, but it performs well as a spread trade against more reckless fiat regimes.

To put it succinctly – yield without having to tolerate a lot of policy nonsense.

Importantly, MXN’s contra-currency role is conditional. It thrives when global liquidity is ample and risk tolerance exists, but discipline still matters.

It weakens during sharp global risk-off episodes. In these cases, carry is unwound rather indiscriminately.

This makes MXN a relative hedge, effective against gradual debasement elsewhere, ineffective against sudden global contraction.

Brazilian Real (BRL) – Volatile, but benefits when real rates are structurally positive versus debasing peers.

BRL is a more extreme expression of the same idea.

Brazil’s history is littered with inflationary trauma, which has produced a cultural and institutional bias toward defending the currency through high real rates.

Brazil’s rates are often some of the world’s highest.

When that discipline is in place, BRL can perform well. Global capital is drawn to positive real yields in a world that’s often starved of them. In such environments, BRL behaves as a high-beta contra-currency, rewarding, but unstable.

The weakness is political cyclicality. Fiscal slippage or interventionist rhetoric can overwhelm attempts at monetary credibility.

As a result, BRL isn’t a store of value, per se, but a policy signal trade. When discipline is real and sustained, BRL outperforms.

E. Synthetic / Portfolio Contra-Currencies

So in our “E” basket, these are not currencies per se, but functional money substitutes.

Synthetic contra-currencies are when fiat money continues to function operationally but fails informationally.

They hedge measurement failure. They work when fiat still functions but no longer informs.

Prices still clear, contracts are still written, and payment systems still work, but money no longer provides a reliable measure of value across time.

In debasement regimes, they’re a type of bridge, used before investors fully abandon the monetary system, but after they stop believing its signals.

In these regimes, investors gravitate toward reference units that better preserve purchasing power or signal real scarcity, even if they are not legal tender.

Inflation-Linked Units (TIPS breakevens, CPI swaps) – Mechanical purchasing-power hedges

Inflation-linked instruments are essentially Treasury bonds that use real returns as the benchmark and not nominal returns. They aren’t inflation swaps and they’re not hard money.

They hedge against measured inflation, not against institutional decay. Their effectiveness depends on the credibility of the inflation index itself.

In early and mid-stage debasement, when statistics are broadly trusted and inflation is politically manageable, these instruments can work well. They allow investors to maintain real value while still looking within the financial system.

For those looking for real returns – inflation-indexed bonds can be an appropriate immunization asset.

But their weakness becomes apparent later in the cycle.

When inflation becomes socially destabilizing, governments face incentives to understate it, redefine it, or regulate around it.

You’d expect this more in emerging markets where checks and balances are less established or secure, but this type of rigging can happen in developed markets as well.

At that point, inflation-linked units hedge yesterday’s problem, not tomorrow’s. They’re therefore valuable, but incomplete.

Commodity Baskets – Energy, metals, agriculture as a de facto currency when fiat loses signal value

Commodity baskets function as a type of shadow currency when fiat money becomes too elastic to anchor prices meaningfully.

Energy, metals, and food represent irreducible inputs to economic activity. They’re what money ultimately competes for.

When monetary policy distorts price signals, commodities begin to act less like assets and more like units of account.

In extreme cases, people stop asking “what is the price?” and start asking “how much energy, food, or materials does this represent?”

Unlike inflation-linked units, commodity baskets hedge real scarcity, not reported inflation.

They perform best when debasement occurs alongside factors like supply constraints, commodity demand, geopolitical fragmentation, or underinvestment in productive capacity.

Their drawback is volatility and cyclicality.

Commodities can fall during demand shocks even as long-term debasement remains intact. They’re useful in a portfolio, but they’re blunt instruments.

How Much of a Portfolio to Have in Contra-Currencies?

There’s no single “optimal” percentage, because contra-currencies are a portfolio property.

The right question is not how much do I own explicitly, but how exposed am I, implicitly, to a single currency regime.

For most, a reasonable explicit allocation to contra-currency instruments (gold, select FX, foreign equity/bond/credit investment in FX, crypto, etc.) is 15-30%.

But the more important idea is that contra-currency exposure should be layered throughout the portfolio, not isolated.

Contra-Currencies as a Portfolio Theme, Not a Bucket

Currency exposure is embedded everywhere.

Every asset is a currency position first and a return stream second.

- Domestic equities = long domestic currency

- Domestic bonds = long domestic currency and policy credibility

- Real estate = long domestic currency + regulation

- Cash = pure currency risk

If your equities, bonds, and credit are all issued in the same currency, then even a 10% gold allocation may not diversify debasement risk by that much.

What “Thematic” Contra-Currency Exposure Looks Like

Equity Allocation

Owning foreign equities is already a currency decision.

- Japanese, Swiss, Singaporean, or commodity-producer equities embed currency diversification

- Multinational firms with foreign revenue streams act as partial currency hedges

- Pricing-power equities reduce currency sensitivity at the business level

This means contra-currency exposure can live inside the equity allocation, not just alongside it.

Fixed Income & Credit

Bond portfolios are often the largest hidden currency bet.

- Domestic long-duration bonds = faith in domestic money

- Foreign sovereign or high-grade credit diversifies currency and policy risk

- Inflation-linked bonds hedge measurement-based debasement

- Curve trades express debasement via rates rather than spot FX

Here, currency diversification often matters more than yield.

Real Assets & Alternatives

Real assets are implicit contra-currencies.

- Gold is explicit

- Commodities are indirect

- Farmland, timber, infrastructure embed scarcity rather than money

- Crypto provides optionality against institutional failure

These assets hedge not just inflation, but policy response risk.

Putting It Together: A Practical Rule of Thumb

Explicit vs Implicit Exposure

- 15-30% explicit contra-currency assets (gold, commodities, FX, crypto)

- Another 20-40% implicitly diversified via foreign equities, foreign credit, and real assets

In practice, this means 35-60% of the portfolio has some protection against domestic currency debasement.

And without relying on one trade or one narrative.

Final Principle

Contra-currencies are fundamentally about avoiding concentration in a single monetary outcome.

Portfolio Example

Here’s one example of how to structure such a portfolio:

- Gold – 15%

- Bitcoin / Crypto – 1%

- Resource Equities – 5%

- Broad / Targeted Commodities (energy, industrial metals, agriculture, softs) – 5%

- Farmland / Timberland – 6%

- Real Estate (Investment, ex-primary residence) – 5%

- Foreign Equities (Higher-Credibility Regimes) – 12%

- Foreign Bonds and Credit (Higher-Credibility Regimes) – 15%

- Commodity-Linked FX Exposure (via equities/credit) – 5%

- Equities (Domestic Broad Beta) – 20%

- Pricing-Power Equities (e.g., staples/utilities) – 6%

- Inflation-Linked Bonds (TIPS / ILBs) – 5%

So, the basic goal with this portfolio is to spread debasement risk across mechanisms rather than bet on a single outcome.

Gold anchors the portfolio against loss of monetary credibility, geopolitical/political (domestic/international) risk, and falling real rates.

A small crypto allocation provides asymmetric protection against institutional or capital-control risk without having it dominate movement in a portfolio.

Resource equities and commodities add exposure to rising real input prices early in debasement cycles.

Farmland/timber and investment real estate hedge longer-term scarcity and financial repression.

Foreign equities and foreign bonds in higher-credibility regimes help diversify policy and currency risk. This reduces dependence on any single fiscal authority.

Commodity-linked FX exposure – which can be expressed through foreign equity, credit, and bond exposure with FX left unhedged – adds a terms-of-trade hedge that benefits when real goods regain pricing power.

Domestic equities remain meaningful to avoid opportunity cost in gradual debasement. But they’re complemented by pricing-power sectors that can reprice faster than costs.

Inflation-linked bonds provide a hedge in early-to-mid stages in that the base return isn’t nominal but a real rate (CPI inflation).

Altogether, the portfolio emphasizes the need to do well in all economic environments, diversify currency exposure, and be able to adapt across debasement phases rather than having precision timing.

As we explained in our article on the debasement trade, there is no perfect asset to trade when it comes to debasement. Each has pros and cons.

By diversifying, we can better cancel out some of the negatives/weaknesses associated with certain assets while taking advantage of their strengths.