Capital Controls

Capital controls – restrictions placed by governments on the flow of capital across borders – have a long and revealing history.

They typically emerge not as first-best policy choices but as desperate measures during late-cycle phases of economic and geopolitical stress.

Understanding capital controls in a historical context reveals not just their mechanics, but what their implementation signals about the underlying fragility of a financial and political system.

Key Takeaways – Capital Controls

- Capital controls are government restrictions on cross-border capital flow.

- They often emerge during economic or geopolitical stress.

- The implementation of capital controls signals systemic fragility and potential paradigm shifts in financial markets.

- Traders and investors should anticipate reduced global capital mobility and potential jurisdictional segmentation of assets.

- This environment elevates the importance of real assets like gold, commodities, and the value of geopolitical diversification.

- Increased sovereign credit risk and financial repression may make nominal bonds less safe, requiring strategies to protect purchasing power.

Historical Context of Capital Controls

Historically, capital controls have been implemented during:

Balance of Payments Crises

When a country faces a sudden stop in capital inflows or a collapse in foreign exchange reserves (e.g., Latin America in the 1980s, Asia in the 1997 crisis), governments often impose controls to stem capital flight and stabilize the currency.

Sovereign Debt Crises

Countries like Greece (2015) or Argentina (repeatedly) have used capital controls to preserve domestic liquidity and prevent a collapse in their financial systems.

Major Wars and Post-War Periods

During World Wars and in the Bretton Woods era (1945–1971), capital controls were standard to maintain fixed exchange rates and manage domestic priorities.

Even advanced economies used them for sovereign flexibility.

Currency Regime Transitions

For example, in 1971, the US temporarily imposed capital restrictions during the Nixon shock to halt gold convertibility and defend the dollar as it broke from the Bretton Woods system.

Deeper Implications of Capital Controls

Rather than viewing them as isolated policy moves, capital controls often indicate the following macro-signals:

1. Decline of Financial Openness

Controls often presage a broader retrenchment from global financial integration.

This was true in the 1930s and again post-2008 as capital nationalism began to rise.

2. Loss of Policy Autonomy Under Global Capital Markets

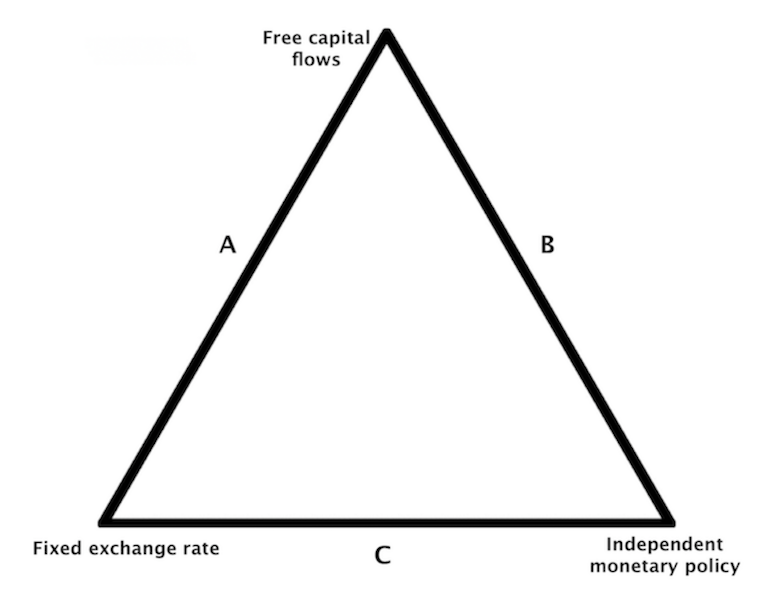

Emerging markets, in particular, find that in moments of crisis, they face a trilemma: they cannot simultaneously have free capital movement, a fixed exchange rate, and independent monetary policy.

This can be visualized below:

For instance, the US is side B of the triangle.

China is side C.

Side A would be countries like:

- Hong Kong

- Eurozone countries in relation to each other

- Denmark under the ERM II, and

- some GCC countries like the UAE, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain (that peg their currencies to the USD but largely have open capital accounts)

3. Late-Stage Cycle of Empires or Reserve Currencies

Capital restrictions frequently arise in the late stages of empire decline – when monetary debasement, high debt, social division, and rising external threats converge.

Controls often reflect a move toward financial repression (keeping interest rates artificially low to borrow cheaply) as governments attempt to trap domestic savings to fund large fiscal needs.

Capital Controls vs. Tariffs

Capital controls and tariffs are similar in that both are elements contributing to a reshaping of capital flows, inflation dynamics, and global political/geopolitical structures.

They’re both symptomatic of a deeper, systemic shift in the global order rather than being mere temporary disruptions.

Just as tariffs act as barriers or interventions in the flow of goods, capital controls act as barriers or interventions in the flow of capital, with both reflecting and contributing to broader geopolitical and economic transformations.

Implications for Today’s World

Given rising fiscal deficits, deglobalization trends, and geopolitical fragmentation, here are key forward-looking implications:

Risks to Global Capital Mobility

- The US and its allies have increasingly weaponized financial systems (e.g., SWIFT sanctions, asset seizures). In turn, this prompts adversaries and even neutral players to reconsider capital exposure.

- China already uses capital controls as a strategic policy tactic, maintaining monetary sovereignty and buffering against external shocks.

Declining Dollar Hegemony

If the US were to move toward capital restrictions in response to a dollar crisis or debt spiral, it would signal an advanced stage of imperial decline.

History shows that when reserve currency nations introduce such restrictions, it’s often the prelude to global realignments.

Asset Allocation and Trader/Investor Response

- Investors should prepare for a world where capital is less mobile, and financial assets may become segmented by jurisdiction.

- Real assets, geopolitical hedges (e.g., gold, commodities), and jurisdictional diversification will become more critical.

- Sovereign credit risk – even in developed markets – may become more material if governments resort to financial repression or enforce inward capital flows. Nominal bonds become less safe when real yields are low even if they can always be paid in nominal terms.

Questions to Consider

- Are we approaching a global regime where “free movement of capital” is no longer assumed?

- If financial repression becomes widespread, how should capital allocators protect purchasing power and optionality?

- How might future capital controls be digital (e.g., programmable CBDCs) rather than bureaucratic?

So, capital controls aren’t merely economic, but political signals.

When they appear, they usually reflect the erosion of trust in systems, currencies, or leadership.

For the strategist or trader, they’re loud warnings that a paradigm shift is underway.