Trading the Coronavirus

When it comes to trading the coronavirus, I don’t trade it tactically, guessing which way stocks, bonds, and other assets and asset classes will move. I am not an epidemiologist, virologist, immunologist, or any type of medical professional, and therefore don’t have insight or an informed opinion into how it’s likely to play out.

I only like to make tactical bets on things that I believe I have an information and/or analytical edge on and keep the size of each individual bet small to keep sensible risk controls in place.

When I don’t have anything that’s worth pursuing (i.e., potential “alpha” opportunities), then I sit in beta and wait patiently. This approach we covered in ‘How to Build a Balanced Portfolio’.

The dynamic

Before the coronavirus, contagious disease wasn’t high up on traders’ list of concerns. No disease since arguably the 1918 Spanish flu has threatened the global economy in the way Covid-19 has.

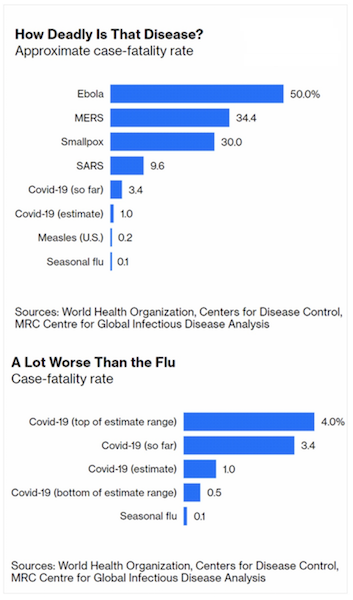

Ebola had a very high fatality high, but for the same reason, affected a relatively small portion of the global population and didn’t spread globally.

Standard seasonal influenza infects millions of people each year and kills tens of thousands annually. But these seasonal illnesses are predictable enough and have low enough mortality rates such they are considered a part of the normal course of events.

The coronavirus is of a character where it’s contagiousness, incubation period, and virulence makes it more lethal than standard seasonal flu. This makes it particularly challenging for governments and health officials, and has made determining its effects on capital flows more challenging for economists and investors.

Gauging its impact on the economy and markets is hard to do. The best we can do is look at past analogues. But when past events aren’t very good models for the present or future, then it’s a very flawed approach.

Investors tend to use the events of the recent past to inform the future. Naturally, to inform their approach on the coronavirus, investors used the SARS epidemic. But SARS was a different kind of virus and China was also a much smaller part of the world economy when it broke out nearly 20 years ago. Because it was an obvious heuristic, this led to complacency, as stocks drew down about 10 percent during the onset of SARS before quickly recovering as the virus burned out. But the SARS analogy was more misleading than it was informative.

At the same time, the Spanish flu from over 100 years ago occurred so long ago that it’s hard to draw parallels.

When the virus hit the airwaves in mid-January, markets reacted, but nothing like the 15 percent plunge we’d later see in late-February. Through the 2-3 week period past mid-January, a narrative emerged that China had taken aggressive enough measures.

Market participants interpreted this as believing the spread would be contained and that the economic impact would mostly be limited to lost demand from Chinese consumers. Countries that export to China, like Australia and Brazil, saw their currencies retreat while countries that import more from China than they export (e.g., US and Mexico), saw their currencies appreciate relative to the renminbi.

Some even suggested that lower Chinese domestic demand could allow importers of Chinese goods to get these products cheaper, leading to lower inflation, lower bond yields, a greater chance of more monetary easing, and therefore higher stock prices. Stocks did decline in the second half of January but rebounded to make new highs.

But past February 19, that narrative changed quickly. Cases began emerging around the world. No longer was it considered a regional issue. The response from global health organizations have been uncoordinated. Different countries have different approaches. Some have been concerned about limiting the spread. Others have been more focused on containing mortality.

Japan, for example, was more concerned about limiting mortality at first. This decision was made to prevent their medical system from becoming overburdened. Since, it has taken more action to close schools and limit spectators attending public events in a greater effort on containment, similar to China and Italy. China has eased its restrictions and people are returning to work. We can see some of this in alternative data, like Beijing traffic.

There’s a trade-off involved. Strict quarantines cut down on economic activity and would see recessions produced globally, and a deeper drop in risk asset markets. But if the virus is contained, then the rebound in growth would be quicker.

If countries opt for more of a treatment approach, then you could expected a longer, but more moderate drop in growth.

Because each region has its own approach, it will likely be some combination of both. Growth will decline and probably lead to a more extended downturn in growth (at the very least, a noticeable impact in Q1 and into Q2).

When it passes, usually demand recovers first, while supply lags behind. It is usually easier to stimulate demand than it is to add capacity or new investment.

Right now markets are more focused on the disinflationary elements and it may take a while before the inflationary elements take hold. And this also doesn’t mean that a rise in inflation will necessarily result. Oil crashed down over 25 percent over the weekend, so headline inflation will remain weak.

We’ve had a lot of inflationary elements thrown at the economy during the course of the past business cycle, including low interest rates and asset buying. But inflation has not moved up materially because what they’ve done is simply negated deflation, which has been mostly a product of high debt relative to income.

Breaking the coronavirus effects down into three categories

With the coronavirus, there are different angles that make up the whole:

(i) The influence of the coronavirus itself – i.e., the health outcomes

(ii) The economic outcomes due to the consequent impact on health (and hence economic productivity) and the impact on business and consumer confidence and consequent government response measures

(iii) The reaction in financial markets due to the economic ramifications

Health outcomes

Every now and then, a virus from another species hops into the human species that we’re not well equipped to deal with. This is what has made the coronavirus a problem for humans, and why it’s unlike other influenza strains that are part of the normal course of affairs. We’ve established an immunological way of dealing with them.

There’s an adaptation period that needs to occur between the virus and the host. That’s the period that we’re in right now.

Sometimes, it passes through, humans adapt, and the virus dies off. H1N1 was a virus that a lot of people became worried about (it went from birds to humans), and it was the same type of strain as the 1918 Spanish flu, but it vanished very quickly. Other times, many of them are particularly disruptive, as this one seems to be.

Based on the data we have seen, the fatality rates associated with the virus are correlated with age (particularly 65+) and those with pre-existing respiratory issues. That’s good for the world in that its lethality isn’t extreme, but it’s not trivial either.

The statistics below compare Covid-19 to Ebola, MERS, smallpox, SARS, and seasonal flu.

While I don’t know what the ultimate health impacts will be, what is likely to happen is that virus will be a temporary nuisance even if the human cost turns out to be large.

The ability to contain the virus is also likely to vary materially based on location.

Countries that are best equipped to handle any outbreak will have effective centralized leadership to execute decisions quickly, a bureaucracy that is effective in carrying out such decisions, a population that is receptive to government directive, and has the medical infrastructure in place to combat the virus.

There’s also a certain level of timing involved. If a government quarantines too stringently, this mitigates the spread, but can excessively put the brakes on economic activity. Any outbreak needs to be met with effective quarantining to prevent it from accelerating, while also easing up as the spread declines.

When this isn’t handled well, it can make the problem worse and cause it to linger, resulting in negative effects for their economy and markets.

Because of its spread globally, and because of upcoming extra testing that is likely to boost the reported numbers of infected people, this will probably increase the amount of panic in the markets. This is also true in the US.

There will be more testing of those who have come down with the flu. When you test for it, you will tend to find it. This will increase the reported figures, and this can also challenge the resources available to hospitals.

Nobody really has an information advantage when it comes to trading the coronavirus, and most trading is currently driven off headlines related to the scare. There’s a psychological component and high level of anxiety around the world, which is spilling into asset prices.

While some of is rooted in logic (bad health outcomes or bad potential health outcomes -> worse economy -> more market volatility), a lot of the action is creating wash-outs due to idiosyncratic cash-flow problems for certain market participants.

The whipsaws also create emotional effects that can have a lasting impact. For example, when bad things happen in markets, it often takes a while for investors to regain their confidence after getting burned in the past.

The spontaneous actions taken by certain countries and different health organizations (public and private) in terms of choosing which events to hold, which to cancel, what kind of travel should be done, who can go to work and who can’t, and so on, has created a menagerie of different things that has made the ultimate impact on economies and markets difficult to predict.

Accordingly, we can probably expect this to last for a while, with an upcoming slew of negative data that will keep market volatility high and be a constant drag on equity markets.

Countries in the southern hemisphere are believed to better pull through the epidemic because of the warmer weather at this time of year.

Economic outcomes

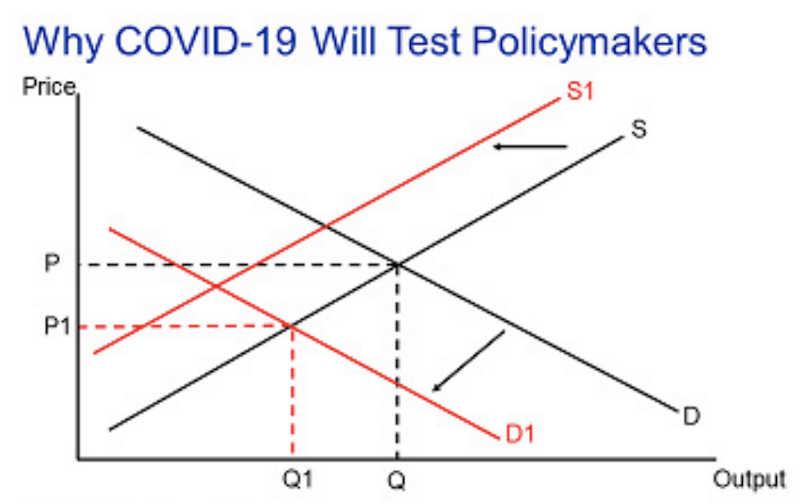

The coronavirus is unique economically because it is an adverse shock to both supply and demand.

The short-run supply shock is largely a consequence of the virus’s influence on global supply chains.

Because the prices of goods, services, and labor vary all over the world, this causes many companies to offshore aspects of product and service creation to different countries where they can get the most bang for their buck.

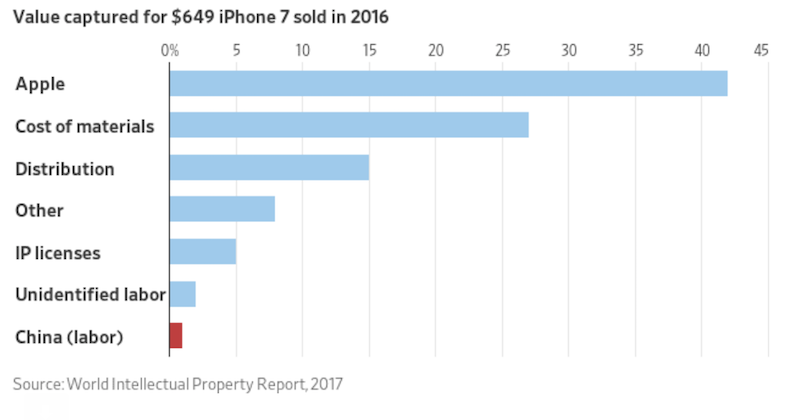

For example, to make the iPhone, Apple will have to pay numerous companies to buy the parts to complete the product and ultimately have it assembled and shipped globally to the various parts of the world in which it’s sold.

A rundown of where the chips and various components are produced:

– Samsung (South Korea) makes the memory and applications processor.

– Texas Instruments and Micron (both based on the US) make the touchscreen controller and flash memory, respectively. Cirrus Logic makes the audio controller.

– Dialog Semiconductor (UK headquartered) makes the power management components.

– Infineon (Germany) makes the phone network components.

– ST Microelectronics (Taiwan) makes the accelerometers and gyroscope.

– Murata (Japan) makes the Bluetooth and WiFi components.

Assembly occurs in in Shenzen, China by Taiwanese manufacturer Foxconn.

China’s improving economic development and increasing prices with respect to labor, property, and energy could also pressure Apple’s margins and incentivize the company to offshore production elsewhere in the future.

Below is a chart of the value captured by Apple on the iPhone 7 in 2016:

Efficient supply chains are like a well-designed machine. But it brings the risk that if one or more of these links becomes unproductive, it can have risks for the business at large. Having supply chain redundancy and excess capacity can help reduce risk in the event of a natural disaster (which is what the virus really amounts to) or a facility accident. But in a competitive world, this adds cost. Backup supply chains aren’t always guaranteed to work either. Any surplus inventory might only last so long.

Falling manufacturing PMIs in China and a fall in South Korean imports from China signal supply chain problems. Survey-based data in the US, such as the Fed’s Beige Book and ISM surveys, suggest supply chain issues are already noticeable.

Supply shocks are inflationary, holding all else equal. Lower supply bids up the price of goods and services, holding demand constant.

Nonetheless, there is also a demand shock aspect as well. A reduction in demand is disinflationary. This is showing up in lower 10-year Treasury yields and lower CPI inflation expectations.

Ultra bond futures (mirrors the US 30-year bond price) is up nearly 25 percent since the beginning of the year (or $44k per contract) – a huge move for a fixed income product.

(Source: Interactive Brokers internal charting)

Below is a stylized example of the economic phenomenon in supply and demand terms and the influence on prices.

(Source: Moody’s Analytics)

Monetary policy can’t do much for a supply shock – lowering interest rates won’t do a whole lot to get supply chains going again. It can help address demand, but only to a degree.

When there is a combination of a supply and a demand shock, this requires both monetary and fiscal policy action in some form.

Monetary policy options

On the monetary policy front, the Federal Reserve could try a range of maneuvers:

– Forward guidance (assert that rates will be kept low for an extended period of time)

– More rate cuts (close to running out of room)

– Quantitative easing (also close to running out of room, so much less effective than during the 2009 to 2014 period)

– Easing credit standards on banks

– Temporary relief to borrowers under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)

– Yield curve control (keeping rates low, but maintaining steepness in a portion of the yield curve to keep a positive lending spread to support the health of the banking system)

– Restart investment into mortgage-backed securities to target interest rate reductions in mortgage markets; this would incentivize refinancing to lower monthly housing payments; in turn, this would give a boost to the consumer by increasing their disposable income

Far less likely in the near-term, but possible in the future:

– Fiscal and monetary policy coordination – (i) monetization of fiscal deficits and/or (ii) skirting the constraints of the increasingly yield-less cash and bond markets entirely and putting money directly in the hands of spenders and savers and tying it to spending incentives

Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy can be slow, particularly when the ideological distribution between the two major political parties is increasingly bifurcated. It’s hard to get people to agree on much, and there are short-term motivations that prevent certain things from getting done at certain times more broadly (e.g., major policy legislation in a presidential election year).

Congress did reach an $8.3 billion deal in early March for emergency funding. But this is small in comparison to the type of relief provided for recent natural disasters.

Government aid packages are designed to provide income and other financial support – e.g., medical and health support, unemployment insurance, support to state and local governments, paid sick leave, tax breaks – to residents and businesses impacted. Moreover, some funding is provided to assist with the development of a vaccine.

In broader economic terms

Quarantining and cutting back on travel is likely to cause a material decline in economic activity and produce a V-shaped recovery once the scare is over. The virus is not likely to have a material long-term impact.

China already showed a bottom in economic activity in late February. Will that continue?

Now other economies, like South Korea, which were infected later, are seeing a more direct hit and seeing a similar growth in the disease that China once did. Will they follow a similar path as China in terms of quarantining and getting the disease under control?

How individual countries handle the issue and how these arcs play out are critical.

The 1918 Spanish flu analogue

The 1918 Spanish flu was one of the biggest demographic shocks in history. It claimed up to 50 million lives (the total number is unknown) and infected 500 million (then about 27 percent of the world’s population). The pandemic came in three waves, before vanishing.

It began in January 1918 in the US. It first appeared in Kansas, not on one of the coasts as you might expect, particularly if it were imported.

In this first phase, it was a severe case of the flu, but then it burned out.

In phase two, it appeared in Europe in the early summer of that year as World War I was still ongoing. But then it also went away.

The worst wave was the third. It came back in October and November and this phase is what produced the biggest demographic shock in modern human history.

At the same time, despite that disruption, by 1919 and 1920 it was virtually gone. The most lethal viruses tend to die out the fastest; they kill the host, then it kills itself.

Despite the massive death toll, it did not produce a sustained dip in the world economy. We can’t say this for certain with respect to the 2020 coronavirus outbreak, but classically this is how these outbreaks have played out.

Prognostications

From the Wall Street Journal, on March 2:

S&P Global is forecasting the U.S. economy to slow to a 1% annual growth rate in the first quarter from 2.1% pace in the fourth quarter of 2019, with a half-percentage point attributable to the coronavirus. For the full year, the effect would be modest, shaving one or two tenths of a percentage point off growth. But that forecast assumes the impact is mainly overseas.

Jamison [UCSF emeritus professor] said such a scenario could still cause U.S. businesses and schools to close, grind transportation networks to a halt, and trim a half percentage point from economic growth for the year. That is enough to slow the economy but not cause a recession, or two straight quarters of economic contraction. He expects any event wouldn’t last longer than several months and be followed by a sharp increase in economic activity.

“You have all the ingredients for an interruption of economic activity here,” said Carl Tannenbaum, chief economist for Northern Trust. “The impact of what’s going on is being underappreciated,” he added. “I don’t think the presumption of a month ago, that this will blow over, is an appropriate posture at this point.”

Market outcomes

When it comes to trading the coronavirus, there may be a level of similarity to other shocks. They tend to be under-discounted at first and over-discounted at the end. It’s always easy to find this when looking back. When you’re in the middle of it, you don’t know where the “end” will be. This makes any idea of trading the coronavirus difficult to do in real-time.

Moreover as the virus spreads globally, we’re seeing less of a sell-off in Chinese markets and more of a sell-off in global markets. Since it spread beyond Chinese borders and as the number of Chinese cases have stabilized (i.e., lower growth rate), we’ve actually seen Chinese markets outperform global markets.

Right now, with the fall in stocks, we know that some part of this is a decline in earnings expectations and a part is an increase in risk premiums (i.e., investors wanting to be compensated more for risk).

Depending on how much we believe is an extra increase in risk premiums, the market is expecting somewhere between a 20-35 percent decline in earnings. The 35 percent is probably too steep, so some aspect is a higher risk premium.

This is a big impact. So when thinking about trading the coronavirus, if you do choose to trade tactically, you need to always think about what’s already been discounted in.

Markets are primarily pricing in the coronavirus as a demand shock. Accordingly, we see both lower growth and lower inflation expectations. This is bad for stocks (which do poorly in such an environment) and good for developed market sovereign debt (which do best in such a scenario). If it were also a supply shock and net inflationary in nature, we’d see things like government inflation-linked bonds and gold do better.

Before the coronavirus broke out, and after it hit the airwaves in mid-January but was largely dismissed by mid-February, market positioning was leveraged heavily in equities. Because of certain technical dynamics, such as volatility shorting (i.e., short OTM puts), this exacerbated the dynamic on the way down.

The 15 percent drop in equity markets was the swiftest in modern history. The S&P 500 fell 13 percent peak to trough from February 20-28:

Hao Hong, BOCOM International, a subsidiary of Bank of Communications:

The market crash in the past two weeks has been truly historic: its probability of occurrence is ~0.1 percent since 1896; the velocity of the plunge and of the VIX surge is the fastest on record; and the 10-year [US Treasury yield] is at an all-time low.

Dean Curnutt, Macro Risk Advisors:

While we are merely days into it, this stress episode is already among the most substantial of the last 25 years, joining an elite group that includes Asian Contagion (1997), LTCM (1998), the WTC attack (2001), the [Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco] Accounting Scandals (2002), the Financial Crisis (2008-2009), the Flash Crash (2010), the Eurozone Crisis (2011-12), the China “re-peg” (2015) and the short vol / VIX event (2018).

All of these events produced big drops in markets that were uncomfortable at the time, but produced large gains following for those who held on and/or bought assets at more attractive prices.

Fixed income

The US 10-year has fallen to less than a 0.5 percent yield, an all-time low.

With the duration of 10-year US Treasuries, all it takes is about an 5-bp upward shift (i.e., +0.05 percent) in interest rates to wipe out the entirety of its annual yield. If inflation averages 2 percent per year, your real inflation-adjusted return is negative.

So, you’ve got duration risk, which means price risk. And even if you were to hold onto that bond for 10 years (which effectively eliminates your price risk, assuming you always keep enough cash on hand to cover any losses), you’re losing money in real terms.

If we want to get even more nitty-gritty about the long-term outlook for US sovereign debt, to fund growing spending deficits, governments will have to sell a lot of bonds. A lot of the current US sovereign debt stock will need to be rolled over in the coming years, up to 25 percent of GDP. Most of the cash to buy the bonds won’t feasibly be available in the private sector. Instead, it will have to come from the central banks to buy the excess supply.

Lower spending and higher taxes are an option, but that capacity is limited and politically unpopular. You can’t lower spending much because a lot of people rely on that income, and you can’t raise taxes much otherwise you risk tax arbitrage behavior and capital offshoring. People will only take so much in extra taxes and cuts in spending programs that benefit (or could potentially benefit) them before they vote out those governments. So, there’s a certain limitation to austerity and how much additional income can be collected.

Even though the funds aren’t available to service all government obligations, it’s very unlikely that they’ll be defaulted on. The debts are denominated in domestic currency in the developed world, which means they have the levers available to manage them (e.g., changing the interest rates, changing the maturities, and changing whose balance sheet it’s on).

Central banks will simply “print currency” in order to buy it. That makes buying these bonds highly unattractive for foreigners because they’ll be worried about what that means for the US dollar when an increasing wave of supply will need to be pushed onto the market.

While foreigners are most concerned about the currency when buying foreign bonds, domestic buyers carry most about inflation to gauge their real return. As we mentioned, both of these factors (currency and real return) are on the downslope, which the coronavirus has exacerbated (bad for the dollar and bad for yields), which means the Fed’s balance sheet is going to have to take on a ton of it in order to keep rates under control.

So, while Treasuries have been the ultimate safe haven during the coronavirus outbreak, owning them is becoming increasingly less attractive as time goes on. (Gold is a popular safe haven option as well. It comes with the drawback of being more volatile than short- and intermediate-term Treasuries and is a less liquid market.)

Equities and other risk assets

The market dynamics can be dangerous for buyers of equities and other risk assets because of the amount of assets that have been bought on leverage.

Central banks, to boost asset prices as part of their quantitative easing efforts, have set the return on cash and bonds low to incentivize investors to increasing move out into equities. This should, in theory, create a “wealth effect” which creates more spending power and greater creditworthiness for households and corporations.

And as the price of equities have gone higher, this has dropped their forward returns. In turn, investors requiring a certain return on equity to make themselves and their clients happy have simply increased their leverage to amplify their returns.

This tends to sow the seeds of its own demise because the markets become increasingly leveraged and more prone to swings in the opposite direction.

In some cases, when you see this happening (i.e., the purchase of risk assets on leverage), you almost want to do the opposite of the crowd (or sit it out) even though your timing might be bad in the short- and intermediate-term.

As the market shakes out, most investors will probably focus most heavily on the impact to revenues and earnings and focus less on how it might impact companies with poor balance sheets – particularly those with a lot of debt coming due in the near-term and may not have sufficient cash on hand to weather it.

Sector-wise, the travel and leisure industries are the most adversely impacted due to headlines impacting consumer confidence. Sectors with more stable cash flows tend to outperform others in this environment.

A company with plenty in liquid reserves and little in short-term debt will probably weather the storm well and be hit in a way that’s out of proportion relative to its fundamentals.

This is causing the market action to be more unusual and more volatile than normal. Investors are being washed out of positions in order to raise cash.

Some types of traders have certain other things going against them. In more tranquil periods, many traders sold OTM and deep OTM put options believing they could simply collect the premiums. They are now having to either liquidate these positions or dynamically hedge against them (e.g., short-sell the underlying securities) as an avalanche of selling comes down on them.

It opens opportunities for those with cash to come in and find quality opportunities, particularly of companies with strong earnings and cash yields with no debt issues (particularly short-term).

Can central bank actions help?

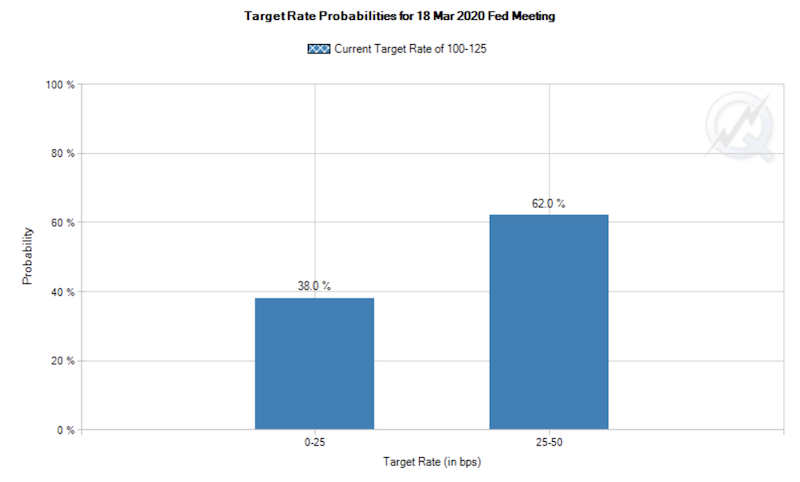

The Federal Reserve, among other central banks, released an emergency rate cut to help boost risk asset prices and help some companies cheapen their liabilities to help counteract declines in demand.

We now see another 75-100 basis points of cuts priced into the March meeting:

(Source: CME Group)

But rate cuts can only do so much. It won’t stimulate more buying and activity from those who have committed to cut back on their discretionary spending.

In developed Europe and Japan, monetary policy is out of room in terms of lowering interest rates and asset buying. The US is now almost at the same point, having to expend its “ammunition” dealing with the outbreak. Fiscal policy is a political process.

So not much stimulation from central banks can be provided because cash and bond yields are already low and represent the discount rates at which equities and most other financial assets are priced off.

Normally a lowering of interest rates would help risk asset prices accordingly. But the drop in earnings expectations is falling in excess of the drop in interest rates, leading to a continued fall in prices.

Offsetting additional declines will need to be accomplished through a combination of monetary and fiscal policy coordination. In other words, to be most effective, it will need to be targeted at particularly strained entities rather than the standard channels of increasing liquidity in broad terms (i.e., cuts in short-term interest rates and asset buying).

Central bank rate cuts and stimulus are helpful and they may work to a degree. But the ultimate economic impact of the disease is unknowable. Therefore, we can’t have indiscriminate faith in the power of the government’s financial levers to counteract it.

Based on what’s currently priced into the curve, the US will be virtually out of further room to cut interest rates after March. The average recession requires about 500bps of cutting. Europe and Japan will need to move toward alternative policies, and the US is now largely in the same bucket.

This makes the question of how the economy and markets will hold up during the next recession more of an unknown, more so than it already was, which central banks are still largely unprepared for.

On top of that, fiscal policy is unreliable given the political obstacles, and lawmakers have come to habitually defer to monetary policy on these matters.

Conclusion

Whether the coronavirus turns into a longstanding economic issue is likely to depend on whether its effects bleed into the credit system.

The virus is likely to remain a public health issue for some time yet. Some of it has to do with the dynamics of the virus itself, such as its long incubation period. In other words, people become infected before displaying symptoms, which causes them to go about their everyday lives and infect more individuals before they have to hunker down to cope with the effects of the illness.

The virus will have human and economic costs, though we are likely to see a V-shaped (or at least a U-shaped) recovery in output once it ultimately passes (and it’s likely to pass, though we don’t know when).

Markets will continue to be strained and volatility will remain high. As this is written in March 2020, we are now 17 percent off the US stock market’s all-time high. Trading the coronavirus is difficult because nobody really has an information edge and is trading in response to rumors and news flow.

Is the future trajectory of US (and global) business, in terms of its future earnings and cash flow trajectory, 17 percent lower than it was just a couple weeks ago?

This isn’t necessarily an opinion that stocks have become undervalued. We could say the stock market was already overvalued and simply became less overvalued. Or maybe it was overvalued and has become “fairly valued”. If you build a balanced portfolio and rebalance periodically, then maybe it’s a time to distribute some unused cash into equities.

At the same time, we don’t want to go on a buying spree and use all of our cash because it might amount to a great buying opportunity. Things are cheaper but certainly not 2009 cheap. Price-earnings ratios in US stocks are about 17x-18x currently versus about 10x in 2009. At the same time, what earnings ultimately come in as is unknown, which is causing a big down move in their prices. Markets price is increased uncertainty by widening bid-ask spreads and moving lower.

Moreover, it could become worse before it becomes better. Countries are still in the early stages of testing their populations for the coronavirus and Covid-19 (the disease that the coronavirus produces). Accordingly, we are likely to continue to get higher reported figures as testing continues and it’s inevitably found more, exacerbating headline-driven market moves.

When it comes to predicting the future, we have to deal with not knowing and recognize that the unknowns will always be greater than the range of things that can be known and position ourselves accordingly.

While some companies with high cash yields and no credit problems have become very attractively priced, we continue to maintain a balanced portfolio that can do well in different environments to largely be immune from what we don’t know.