How to Invest 1 Million Dollars

So, you’ve made one million dollars – or an amount that, when you put it to work in a prudent way, can generate you a solid passive to semi-passive income stream in perpetuity.

How to invest 1 million dollars

In a previous article, we went through the importance of having a balanced portfolio.

Namely, how do we have a strategic asset allocation mix that avoids environmental bias, avoids large swings and drawdowns, and can preserve and grow wealth in any economic environment?

We went through the logic behind the idea why the average investor is going to run into issues in learning how to trade or invest. It’s very hard to predict which stocks or which asset class is going to do best over the short- and intermediate-term.

At any given point, are stocks a good thing to invest in? Are bonds? Is gold? Commodities?

The consensus is already built into the price.

We can’t pick what asset class is going to do best over the next day, week, month, year, or even decade.

But what we do know is that each asset class will perform differently. If you can mix and diversify them well you can keep the big upside in your portfolio without having unacceptable downside.

If you have one million dollars to invest, you will probably want to use a mix of cash equities and bonds as the “growth” or “yield” portion of your portfolio.

You can invest all of it into cash equities – say 80 percent developed market stocks and 20 percent emerging market stocks – and expect to achieve some 5.5-6.0 percent annualized.

That alone will give you $55k to $60k per year in income.

With that said, stocks are a volatile asset class and can and will draw down 50-80 percent over the course of one’s lifetime.

The Great Depression saw stocks decline 89 percent peak to trough.

The NASDAQ declined by 80 between 2000 and 2002 when the expectations of the future fundamentals of internet and technology companies were too high.

The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 saw stocks decline 51 percent.

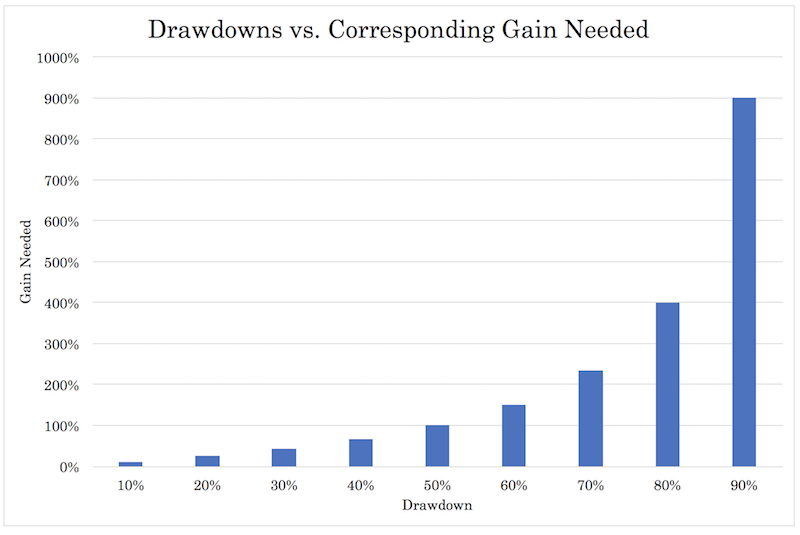

You never want to put too much of your portfolio at risk. Every asset class has a period in which it does well and a period in which it does poorly. Having 50-80 percent drawdowns is not necessary. The larger the drawdown the larger the gain needed to dig yourself out of it.

At a certain drawdown level, you’re basically back at square one because it’ll be impossible to recover from.

Limiting losses is your most important consideration and carries with material compounding effects over the long-run.

How to design the portfolio

Having broad diversified exposure is key. Most individual investors should probably not pick individual stocks.

Most traders and investors are biased toward their own domestic stock markets and particularly companies that are popular in the media. Companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook might be big and successful, but they usually have ample amounts of growth already discounted into their prices. The market is just as likely to discount high growth as too high or low relative to low growth.

Consequently, your starting point should be that almost everything is an equally good or bad bet.

Investors trying to preserve and growth their wealth over time can benefit from wide strategic exposure. Instead of individual names, this can include liquid ETFs like VOO (a cheaper version of SPY), VWO (a cheaper version of EEM), and VT (a type of all-world ETF). Example bond ETFs include VCT, VTEB, VCIT, and VCSH.

We not only want to have US and developed market exposure, but a smaller amount of emerging market exposure can be an important diversifier and return-enhancer as well. (This was discussed more in the following article.)

It would also be useful to put some of it in cash bonds as a source of capital preservation.

Let’s say we put half of it in cash equities ($500k) and half in cash bonds ($500k).

If you put this in a mix of half low-cost stock ETFs (some 5.5-6.0 percent return) and half into low-cost bond ETFs (some 2.5-3.0 percent return), that would produce a return of $40k to $45k per year.

But having this 50/50 type allocation doesn’t balance out our portfolio. Stocks are more volatile than bonds, so stocks would still dominate the price movement. In that sense, it’s more of an 85/15 portfolio in terms of the risk distribution.

We can add in bond futures to help achieve better balance.

With only stocks and bonds, we are also not well balanced relative to movements in inflation. Both stocks and bonds benefit from lower inflation. Commodities and gold can excel in periods of higher inflation and have a useful role in building a balanced portfolio and reducing your risk.

Limiting drawdowns

To limit your drawdowns, you’d prefer not to have environmental bias. With only stocks, you’re fundamentally betting on a future environment in which interest rates remain favorable and/or growth remains above expectation.

When that isn’t true, stocks can fall swiftly and potentially wipe out years of progress.

This is where asset classes like bond futures, gold, and commodities come into play.

We detailed in the balanced portfolio article that to maximize our reward to risk, we are best keeping equities to around a 20-30 percent allocation in the portfolio. That’s kind of the sweet spot between risk and reward.

Fixed income takes a higher nominal dollar amount in the portfolio because it has lower duration (bonds typically have a fixed end date whereas the cash flows of equities are theoretically perpetual).

We can get this type of exposure through bond futures. The US Treasuries market is the deepest and most liquid fixed income market globally and also has a liquid futures market.

To balance out $1 million worth of equities, we could use the following amounts:

– 2 contracts of ZT (2-yr US Treasury bond futures)

– 2 contracts of ZN (10-yr US Treasury bond futures)

– 1 contract of ZB (30-yr US Treasury bond futures)

This would give us notional exposure to around $2 million worth of fixed income.

For inflation-hedge assets, we can reserve 5-10 percent of the allocation to gold and another 3-5 percent or so to broad commodities exposure.

We could accomplish this with the following:

– 1 GC (Gold futures)

– 8 AIGCI (Bloomberg commodities index)

Our total margin costs of these futures contracts would be about $43k. If you’re in a margin account, you would probably around have hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of margin availability remaining after the $1 million outlay to cash equities and bonds.

Portfolio

So, this would be our total portfolio:

– $1 million in broad cash and bond equities exposure

– 2 ZT (2-yr US Treasury bond futures)

– 2 ZN (10-yr US Treasury bond futures)

– 1 ZB (30-yr US Treasury bond futures)

– 1 GC (Gold futures)

– 8 AIGCI (Bloomberg commodities index)

Breaking it down by allocation:

– 22.5% equities

– 66.5% fixed income

– 8% gold

– 3% commodities

Our notional exposure, adding up the allocation from the cash securities (our $1 million to invest) and futures (another $1.044 million), comes to $2.044 million.

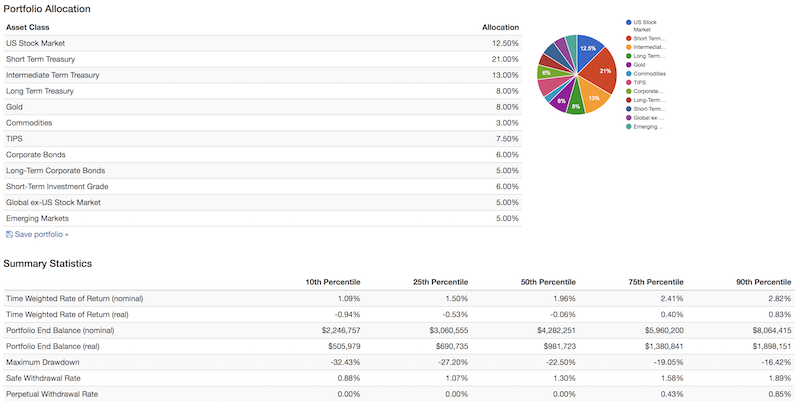

If we simulate the results of this allocation, how does it do? (Please see the Monte Carlo simulation part of this article for an overview of how this is done.)

We simulate out 75 years.

Our expected drawdown over this time is 23-33 percent, going from the 50th to 90th percentile expectations.

Multiplying this by our notional exposure, this comes to $470k to $674k in terms of gross drawdown.

Our expected return is 1.96 percent multiplied by our notional, or about $40k per year.

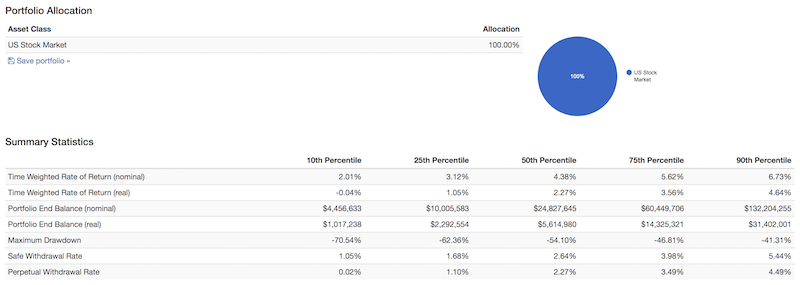

If we were to not do any diversification, what would our expected drawdowns be?

In other words, if we just put this $1 million in an “all stocks” portfolio, what would our expected drawdown over the next 75 years be, covering this same confidence interval?

Stocks only Monte Carlo simulation

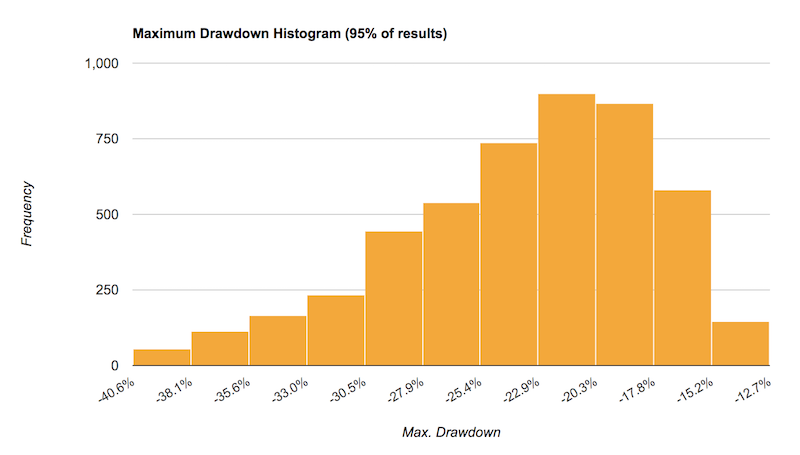

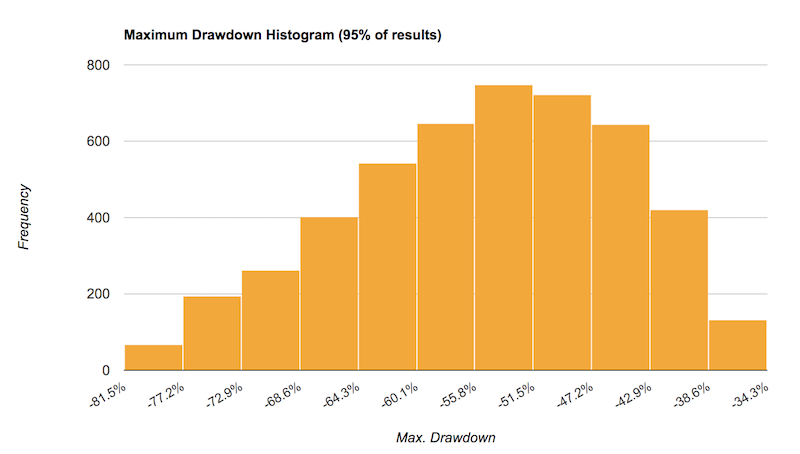

In this case, our drawdown ranges from 54 percent to 71 percent. An “all stocks” portfolio has a particular environmental bias, so even though we are only using cash equities in this case – i.e., no leverage – our distribution of expectations is wider in the drawdown figure.

In this case, it’s telling us that we could drawdown by as much as $540k to $710k.

Our expected return is estimated at about $44k per year.

This illustrates how using moderate amounts of leverage to become better diversified can help improve our risk profile without sacrificing return – or improving our return without having to take on more risk.

In terms of our distribution of drawdown expectations:

Balanced portfolio

Stocks only portfolio

Conclusion

Building well diversified portfolios is a stronger approach to investment management for both retail and institutional investors over the long-run.

Because of the difficulty of adding alpha in the equities market or any asset class – and the large drawdowns associated with having a certain environmental bias in a portfolio – more efficient portfolio construction is likely to take on an increasingly greater focus in the asset management industry going forward.

Most investors are best off engineering their portfolios to efficiently replicate beta returns in a way that assumes that the future is unknowable. How can they get to a “neutral” position to smooth out the bumps without sacrificing returns? Risk and reward don’t have to be a purely linear thing.

This is the process of blending asset classes in a way that achieves a efficient strategic market position, or one where one’s returns are not dependent on a specific type of economic environment playing out.

This can help lower your drawdowns and avoid the same level of volatility seen in the stock market. (Though you can replicate the volatility of the stock market while achieving higher returns if the portfolio is built in an efficient way.)

The way most portfolios are constructed is by linking the alpha to the betas. For example, an equity manager will be inclined to be biased long the market and attempt to pick stocks. That performance will then be benchmarked against an index most closely resembling what they do. So essentially their alpha generation depends on their basket of stocks outperforming an index like the S&P 500.

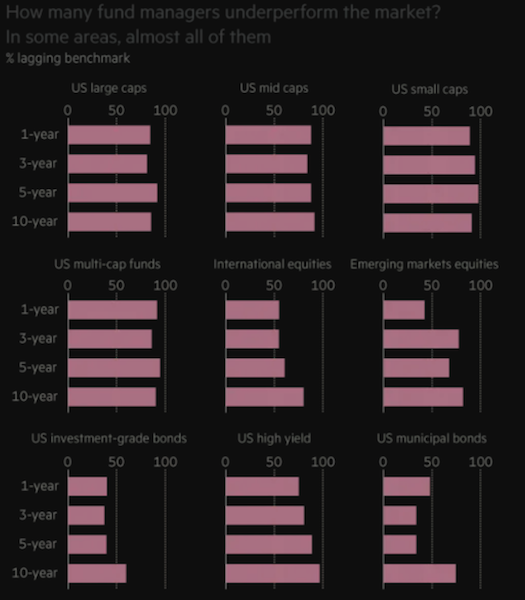

But this is hard to do. Alpha is inherently a zero-sum game. Adding value in excess of a benchmark means somebody else is losing. Very few managers outperform basic benchmarks over time due to transaction costs, like as slippage, commissions, margin interest fees that actually make the process negative-sum in nature.

About 95 percent of managers across all asset classes, regardless of specialty, don’t outperform a representative benchmark over time. For equities, in particular, the challenge managers face in outperforming the market is apparent after just one year.

Those who do try to generate alpha in the best possible way will do so by avoiding having to link them with betas. And they will be sensibly constrained by controls that prevent concentration risks beyond a certain level. This will help minimize the number and size of the drawdowns they experience, such as not having more than a certain percentage of one’s portfolio invested in any given instrument, security, industry, theme, or asset class.

Hedge funds have the greatest leeway when it comes to engineering alphas. Other types of managers are constrained in certain way. They often have limitations in which way they can play the market. A common example is the prohibition of short-selling for many types of managers. Or they may be limited in the ways in which they can use leverage as a tool to help them achieve higher returns or build more efficient portfolios, such as using leverage or leverage-like techniques to get asset classes to exhibit the same risk.

Because of this greater freedom, many look toward hedge funds and hedge fund-style investing as a way to help them more efficiently create portfolios.

For anyone with any amount of money to invest and wants to do so within the context of a self-directed account, they should strive to have an excellent strategic asset allocation mix that can hold up and build wealth through different environments.