Trading Gurus: Skill, Luck, or Neither?

Are trading gurus skilled, lucky, or playing a different game altogether (sales)?

We’ll present the different angles, common narratives, and see what the real story is.

Key Takeaways – Trading Gurus: Skill, Luck, or Neither?

- Trading can be skill-based depending on edge and execution. Casino gambling is always a negative-expectancy game where the house wins over time given enough trials.

- In markets (and games like poker), you can tilt the odds by choosing when to bet, how much to risk, and cutting losses while letting +EV (expected value) scenarios run.

- Short-term big wins don’t necessarily prove skill. They often just reflect luck and variance.

- “Trading gurus” often showcase a few lucky outliers and hide the many quiet losers (survivorship bias).

- A real edge comes from a tested strategy, risk control, and enough capital to a) survive long losing streaks or drawdowns and b) make trading worthwhile to begin with.

- Institutions rely on data, backtests, and risk-adjusted metrics.

- Trading isn’t automatically gambling, but most retail traders are effectively gambling because they trade without a proven edge or solid risk plan.

Distinguishing Trading from Gambling

The line between trading the financial markets and gambling in a casino is often blurred in the public eye.

Both involve risking capital with an uncertain outcome to varying degrees, and both will psychologically elicit similar neurochemical responses involving risk and reward.

What makes them different are the underlying mechanics, mathematical probabilities, and the role of human agency.

Understanding this distinction is the first step in transitioning from a speculator who’s basically just taking a guess to being a professional trader.

The Mechanics of Gambling: A Game of Negative Expected Value

Gambling, specifically in the context of “house” games like roulette, slots, or lottery tickets, is defined by rigid, unchangeable probabilities.

These games are mathematically engineered to have a negative expected value (-EV) for the player.

In a game of negative EV, the odds are fixed against you.

For example, in American Roulette, betting on “Red” pays 1:1, but the presence of the green “0” and “00” means you have less than a 50% chance of winning.

As long as the house is capping the maximum bet size for prudent risk management purposes, they’re going to win with enough volume.

Accordingly, for the player, no amount of “strategy,” positive thinking, or bankroll management can alter the static probability of where the ball lands.

The Law of Large Numbers dictates that while you may experience short-term variance (winning streaks), if you play long enough, you are statistically essentially guaranteed to lose.

In gambling, time and the number of trials is the enemy; the longer you play, the closer your results will converge to the mathematical expectancy of the game: the edge favors the casino.

Trading and Poker: Games of Incomplete Information

In contrast, trading and poker are classified as “games of incomplete information.”

Unlike a slot machine, where the internal algorithm is fixed, financial markets and poker hands are dynamic environments.

Here, outcomes aren’t predetermined by a rigid house edge, but are influenced by a convergence of variables, probabilities, and, most importantly, player decisions.

The defining characteristic of trading is that the participant can influence the expected value of their actions.

An educated trader doesn’t accept fixed odds; they hunt for skewed risk-reward scenarios.

The formula for Expected Value in this context is:

EV = (Probability of Win * $ if Win) – (Probability of Loss * $ If Loss)

In trading, unlike roulette, you have agency over these variables.

You can choose not to trade (fold) when the setup is poor.

You can cut a loss early to minimize the amount lost, or let a winner run to maximize the amount won.

So by exercising skill and discipline, a trader can flip the odds to create a Positive Expected Value (+EV) system.

How do you do this?

That’s beyond the scope of this article, but we have various articles on strategies and different approaches to doing that, including more passive ways.

Related: Examples of Trading Edge

How Negative Expectancy in Trading Can Fool People

A trader can buy a bunch of stocks and make a profit.

But most of the time, they aren’t beating an index, especially long-term.

Transaction costs defray profits. So do taxes. Behavioral errors also compound the issues – e.g., buying stocks when they’re hot and getting scared out of them when they’re not.

At the same time, they’re still likely to come out ahead

“Optimal Policy”

The strongest evidence that trading and poker are skill-based pursuits (rather than pure gambling) has to do with the existence of “winning policies.”

Researchers have developed poker bots (like Pluribus or Libratus) that consistently beat top human professionals, if they get enough of a sample size.

If poker were pure gambling, a bot couldn’t statistically dominate over a large sample size; it would essentially be flipping coins.

The fact that these bots win shows that there is an “Optimal Policy” – i.e., a mathematically superior way to make decisions based on available information.

In trading, this concept of policy is identical to a trading plan. A trader operating with a gambling mindset chases the dopamine hit of the “win.”

A trader operating with a professional mindset focuses on the execution of their policy (strategy or strategies).

They understand that individual trade outcomes are close to random (variance) – or for long-term assetholders, short time horizons are very close to random – but if their strategy is +EV, their long-term equity curve will rise.

A basic example is simple index funds. Companies produce profits, which in turn get capitalized into the share price or returned back to you through dividends and distributions.

Debunking the Guru Narrative: The Survivorship Bias Trap

Aspiring traders often fall for “trading gurus” – instructors or influencers who flash screenshots of massive gains and claim to possess a secret formula for wealth.

But mathematical simulations reveal that these success stories are often not the result of skill, but of statistical anomalies weaponized to sell courses.

The Simulation: Success Without Skill

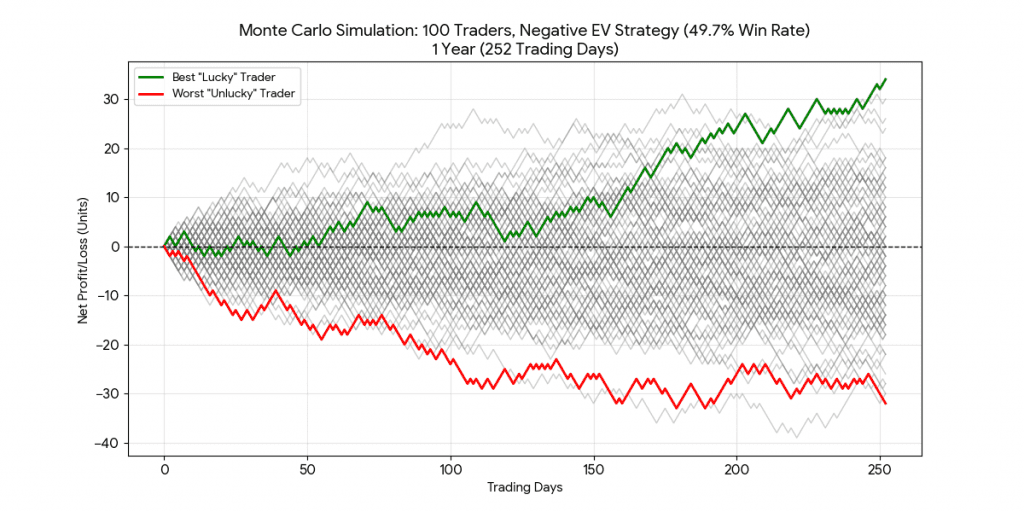

To understand how a worthless strategy can produce “profitable” traders, we look to a specific simulation involving Net Zero Expected Value (EV).

Let’s do an experiment where we simulate 100 traders utilizing a strategy that has absolutely no statistical edge.

This is a “coin flip” strategy: over an infinite timeframe, the expected return is exactly zero (ignoring commissions). Logically, one might assume that all 100 traders would simply break even.

When factoring in round-trip commissions, let’s say the odds are 49.7%/50.3%.

Probability moves in a “random walk.”

In the simulation, despite the strategy being mathematically worthless before commissions (EV = $0), the results are quite varied due to short-term variance.

- The majority of traders hover around breakeven or are with +/- 20 profit units.

- In the real world, due to behavioral errors, a large portion would blow up their accounts due to a run of bad luck.

- Most lose money.

The traders that were profitable are not “better” than the others. They followed the exact same rules.

They simply walked a “lucky sample path” where the distribution of heads and tails favored them in the short term.

The Survivorship Bias Trap

This statistical reality creates the foundation for the “guru trap.”

Results are rarely audited over long time horizons. Instead, the industry relies on survivorship bias.

Survivorship bias is the logical error of concentrating on the people or things that “survived” some process and overlooking those that didn’t because of their lack of visibility.

- The Parade of Outliers – The Guru will take traders from the simulation (the lucky outliers) and present them as proof that the system works. They are interviewed, given testimonials, and paraded as “consistently profitable.”

- The Silent Majority – The majority of the traders who lost money or broke even are ignored.

- The “Dedication” Gaslight – When new students fail using the same Net Zero EV strategy, the Guru doesn’t blame the system. Instead, they point to the successful students and say, “They made it work because they were dedicated. You failed because you didn’t have the right mindset.”

This narrative effectively shifts the blame from a mathematically flawed strategy to the individual’s psychology or shortcomings.

It convinces the student that the variable for success is effort, rather than mathematical edge.

When you understand this trap, a trader realizes that a few screenshots of high returns are meaningless without a large sample size and a verified, backtested edge.

What Actually Goes into Profitable Trading

Mathematical “edge” is highly important but it still doesn’t guarantee a profit.

You can still blow up or dig yourself into a non-recoverable hole even with edge.

The gap between theoretical probability and realized performance is a function of variance, psychological endurance, and it helps a lot if you have plenty of capital available.

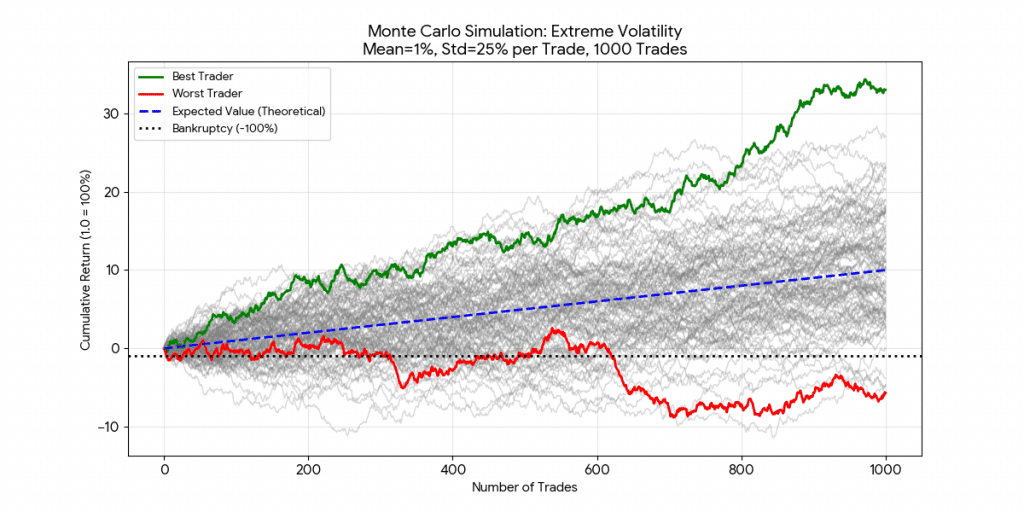

High Risk, Even with an Edge

It is a common misconception that a Positive Expected Value (+EV) strategy acts like a relentless money printer.

In reality, probability means you’re going to get large deviations that work for and against you.

There’s Sequence Risk.

Most traders in our previous example faced a drawdown greater than their initial principal.

This implies that to survive a “winning” strategy, one often requires quality capital reserves. If you start with $10,000 and your strategy has a standard deviation that swings your equity down by $12,000 before swinging it up to $50,000, you would have gone bust (“gambler’s ruin”) long before realizing that profit.

Let’s run this kind of exercise:

- Edge = Positive (Mean return = 1% per trade)

- Win Rate = ~51.6% (Implied by the Mean/Std distribution)

- Volatility = High (Standard Deviation = 25% per trade)

We can see that with this edge we get an expected profit of around 10% after 1,000 trades.

We can also see that despite this edge there were many losing traders.

If any of them were applying leverage – e.g., via futures or other higher-leverage techniques – this would have gone poorly.

Losing money after 1,000 trades with a winning strategy demonstrates that the “long run” is longer than many humans can endure.

This is due to the Law of Large Numbers. Convergence to the expected mean takes time; 1,000 trades may simply be too small a sample size to smooth out the variance of a volatile strategy.

This is why in some strategies volatility control and tail risk protection is so important.

Related: Skill in Markets: How Long Does It Take to Show?

The Institutional Approach (Skill)

Retail traders are often sold the dream of “reading the tape” or finding “magic patterns,” but institutional trading operates in a different way.

Quantitative vs. Discretionary

Institutions don’t rely on “feel.”

They rely on quantitative research and understanding the cause-effect mechanics of why markets do what they do.

They hunt for statistical mispricings; tiny inefficiencies in the market (e.g., the price of gold futures vs. gold ETFs drifting apart by 0.05%) that can be exploited.

Backtesting

A Guru might show you a chart where a strategy worked five times in a row.

An institution will run that strategy through 20+ years of tick-data, accounting for slippage, commissions, and market impact, and then stress-test it with Monte Carlo simulations and potentially other synthetic data to see how it performs during a market crash.

Clean Data Acquisition

Institutions pay millions for “clean” data feeds because they know that a strategy based on bad data is a hallucination.

Guru Metrics are Misleading

The “guru industry” thrives on metrics that trigger dopamine but hide risk.

Win Rate

A 90% win rate sounds incredible, but it’s meaningless without the risk-to-reward ratio.

If you win $1 nine times and lose $10+ once, you have a 90% win rate and a negative expectancy.

For example, shorting OTM options works great most of the time until you have a large loss.

Dollars Per Month

“I made $10,000 this month!” is a useless statement without knowing the account size.

Making $10,000 on a $100,000 account is impressive (10%), but not necessarily sustainable (100%+ per year).

Making $10,000 on a $10,000,000 account is a rounding error (0.1%).

The Real Metrics

Professionals care about risk-adjusted metrics like the Sharpe ratio (return per unit of risk), maximum drawdown, and profit factor.

These measure the quality of the returns, not just the quantity.

Conclusion

The distinction between trading and gambling is mathematically real and has to do with the quantification of an edge.

But in practice, it’s often illusory and there’s not enough of a sample size to tell.

Casino games like slots, roulette, etc., offer a fixed negative outcome; the financial markets, on the other hand, offer the theoretical possibility of a positive expected value (+EV).

A trader can technically tilt the odds in their favor, moving from a gambler to a professional operator.

Then it’s a matter of risk management, scalability, and repeatability.

The “success stories” (or ostensible success stories) that dominate retail trading are rarely the result of a rigorous process.

They’re primarily products of survivorship bias. As simulations demonstrate, a completely worthless strategy will still produce a percentage of big winners of a seemingly long enough time horizon purely due to random variance.

These lucky outliers can then be packaged and sold as proof of a “system,” while the silent majority of losers are ignored or they “weren’t dedicated,” “made too many errors,” “didn’t follow the system,” etc.

Ultimately, while trading isn’t inherently gambling, most retail traders are effectively gambling without realizing it – at least until they have enough bad results to realize they need to do things differently.

They mistake a “lucky sample path” for skill and confuse short-term variance with long-term edge.

Genuine profitability is possible, but it requires accepting that even a winning edge comes with volatility and drawdowns, and that luck has a far larger role in short-term results than most are willing to admit.

Related