Trading By Feel – Does It Work?

Over the years, markets have become increasingly made up of quantitative oriented traders, both in market making and actively setting prices.

Math, algorithms, and specific rules are used in these strategies to strip away emotion, gut feel, and behavioral errors that are common with humans.

At the same time, intuition-based trading is still part of markets, where they’re going by their own reading of markets, even more or less separate from their own discretionary analysis.

Does it still work?

We’ll take a look.

Key Takeaways – Trading By Feel

- Trading by feel for an experienced trader isn’t wild guessing, like it generally is for a new trader. Instead, it’s a discretionary input based on subconscious pattern recognition.

- While purely emotional trading is terrible, developed intuition is a valid edge, provided it’s backed by successful experience and risk management.

- Mechanism – “Gut feel” is your brain processing micro-behaviors (like sluggish price action despite high volume) faster than logic can.

- Example – A trader might use their gut feeling to spot exhaustion in markets. If a high-flyer stalls on good news (“churning”), it might not mean selling or any kind of rash decision, but instead selling premium at a level you’d be comfortable selling the stock (covered calls). You profit from time decay while the stock chops sideways.

- Genuine intuition is cold and observational. Impulse is hot, fearful, or hopeful. If it’s emotional, it’s anxiety, not insight.

- Use intuition as a filter or as a basis to look deeper. If your process says one thing but the trade just seems wrong, let it trigger a deeper review.

“Gut Feeling” at Different Levels of Expertise

Novice traders often mistake a gut feeling for something more accurate than it actually is.

They buy because they “feel” a stock is due for a pop, or sell because they’re scared.

But for an experienced professional, what feels like a hunch is another layer of sanity checking running in the background. It’s internalized experience.

And whether it’s top-down or more of a final check is up to the trader.

For example, some pursue trades based on their current intuition of what’s correct.

Some have their entire process set up and then only sign off on trades if they “feel” right.

The Science of Intuition

Neuroscience suggests that intuition is high-speed pattern recognition.

The conscious mind (the prefrontal cortex) is slow and can only process a limited number of variables and information at once.

However, the subconscious mind can process information quickly.

When a veteran trader gets a “bad feeling” about a trade, it’s often their brain recognizing a specific mixture of variables.

For example, if:

- stock prices are high relative to traditional measures

- interest rates are rising

- inflation is too high

- oil prices have gone up

- the dollar is rising

- unemployment is low, and

- credit spreads are tight…

…their gut might tell them that it’s not a great environment for further gains in the stock market.

Accordingly, they might be more cautious when it comes to long stock trades.

At the same time, it’s not very deep analysis. It’s simply a superficial recognition of a smattering of macro factors, that in turn leads to a binary-ish type of hunch.

The brain flags the danger before the conscious mind can articulate a fully fleshed out reason for the logical reason for it.

The “gut” is simply the immediate output of experience you’ve been building for years.

The Edge

A quantitative algorithm is often rigid with if/then type of logic.

An algorithm sees that a price has crossed a moving average as a bullish signal. A human with hours of observation and success in markets sees how it crossed.

Did the price smash through on high volume, or did it drift upward on low volume where there’s just not a lot of selling?

Experienced traders can notice micro-behaviors and relevant nuances that can be difficult to program into an algorithm, such as the way a bid/ask spread might widen before a drop, or how a stock ignores a sector-wide rally.

The human trader can synthesize this noise into a narrative that the math hasn’t caught up to yet.

It needs to be some type of structural and repeatable edge based on the cause-effect mechanics of markets.

The “Finger-tip Feel”

A trader might describe a market as “wobbly” even when it’s strictly trading flat.

They notice that despite good news, the stock isn’t rallying. Or it rallies on the news, but it can’t hold.

They see that every time the price ticks up, it’s immediately met with a large sell order.

Sometimes you can tell that a large order is being pushed through the markets in proportion to the volume in a market or at certain increments of time. (There are VWAP and TWAP algorithms that do this.)

For example, a stock materially beats earnings, which leads to a nice bump in its price, only for selling to push it back down below the price it was even before the good news.

Conversely, a market feels “buoyant” when earnings are flat and there’s little volume. The intuitive trader senses the underlying fragility to the rally.

This allows them to adjust their risk before the move actually happens.

Can You Develop Intuition Without Previous Trading Success?

I think there are cases where this actually could be true.

For example, let’s say before you start trading – or at least trading in a material way – you extensively backtest various allocations.

Eventually you settle on a mix of assets that give you an acceptable return and acceptable risk (volatility, drawdowns, underwater periods, etc.) at an acceptable return-to-risk ratio.

When you put it on and markets move and start to deviate from your optimal allocation bands, the gut feeling you developed from your backtests – i.e., having allocations too high or too low relative to another – can help you spot that it’s not optimal and push you to rebalance.

For example, if stocks are too high relative to bonds, stocks will simply dominate the portfolio because stocks have longer duration.

Also, if your gold allocation is close to your stocks allocation, this might also trigger a feeling that this isn’t optimal because you’ve seen suboptimal effects during your simulations.

If you watch markets daily you can also feel when something is out of balance in your portfolio because it’s simply impacting your P/L by too much.

A Baseline Allocation to Compare to a More Intuitive Approach

One of the benefits of having some type of baseline mix is that it acts as a benchmark against your active management decisions.

If you have a “beta” portfolio (a strategic asset allocation mix) that you don’t touch outside of rebalancing, you can then test your active trading against it to see if you’re adding value.

If you are, great.

If you’re not, that can also be great as beta is essentially free money over the long run and not actively trading can free up your time for other tasks. You’re still in markets, just not so day to day with it all.

Case Study: The Exhausted High-Flyer

To understand how “gut feeling” can function as a legitimate trading edge, let’s look at a specific market scenario where we look at a case of an exhausted momentum stock.

The Setup vs. The Disconnect

Imagine a popular stock, perhaps a semiconductor or AI stock, that has rallied 40% over the last two months. Looking at charts, the candles are green, the moving averages are fanned out in a perfect bullish formation, and the RSI suggests strong momentum.

A strictly technical trend-following or momentum algorithm might look at the factors and signal a “Buy” or “Hold.”

However, an intuitive trader watching the intraday action notices something wrong. The “texture” of the trade has shifted.

Perhaps positive news broke that morning, a raised price target, yet the stock didn’t spike. Instead, it opened flat. Or a new partnership was announced, which led to a price spike, but it later sold off and retraced the entire move (and perhaps then some).

Throughout the session, the volume is high, but the price isn’t moving. This is known as “churning”: heavy participation without progress, indicating that for every buyer, there’s now an equally aggressive seller unloading.

The trader notices that every time the stock tries to push forward, it gets slapped down.

The price action feels heavy, like a runner trying to sprint uphill in mud. The lagging indicators say “Trend,” but the trader’s gut says “Exhaustion.”

The Intuitive Trade: Sensing the Ceiling

The intuitive trader recognizes that the buyer pool is likely tapped out.

Everyone who wanted to buy has already more or less bought; the only people left are the latecomers who might end up holding the bag.

While a trend or momentum algorithm predicts a continuation, the trader senses a transition.

Nonetheless, the intuitive trader also knows that momentum requires respect.

Shorting a high-flyer outright is dangerous. A basic bounce in price could rip through a stop-loss.

The intuition here isn’t necessarily about prices falling, but rather that the upside is now more capped. The easy money has been made.

And factoring in fundamental factors (e.g., earnings high relative to price) and the fact that stocks and asset prices integrate all known information and generally appreciate by a single-digit percentage per year, that the momentum being extrapolated by many isn’t likely to pan out.

The Execution: The Premium Play

Instead of placing a risky short bet or simply getting out of the stock, the trader leverages this intuition to sell premium.

If they already own the stock, they might sell covered calls against their position.

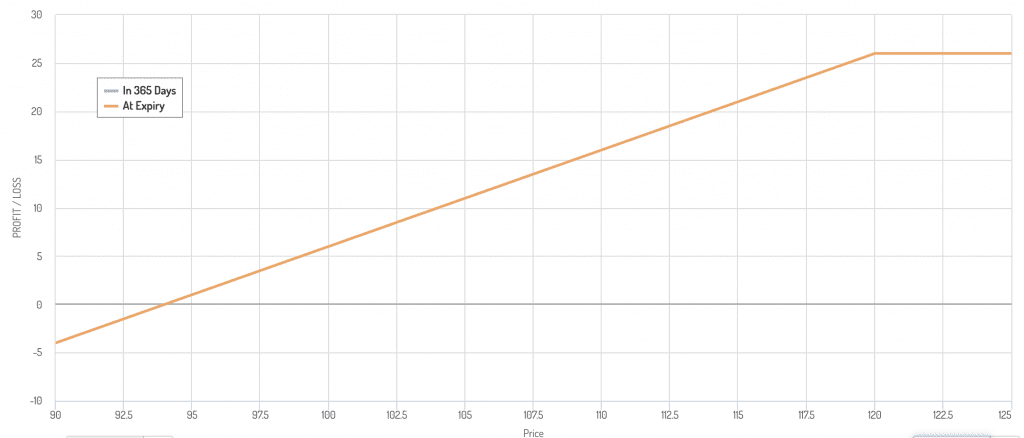

Their payoff diagram looks like this:

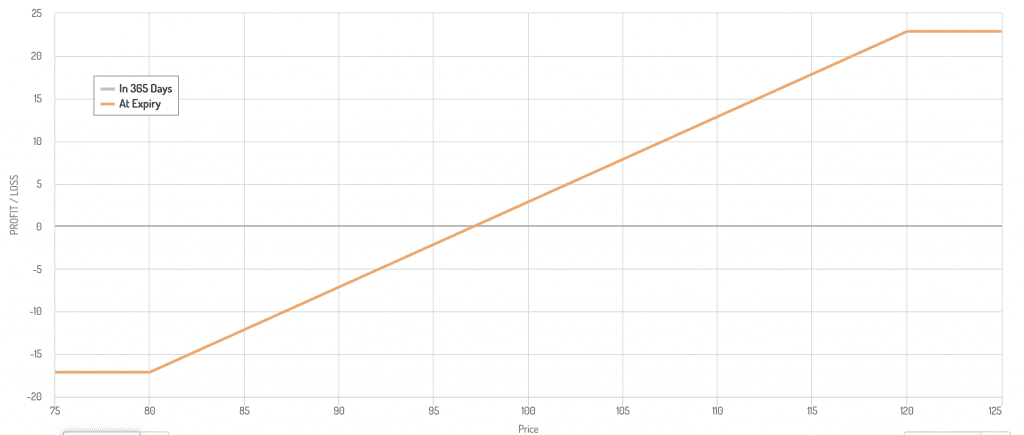

Or even overlay a collar (long stock, short call option, long put option) on their long position to cap upside and downside.

The logic here is that because the stock has been flying high, implied volatility (IV) is likely elevated, making call options expensive. The trader sells these expensive calls to optimistic buyers who look at the 40% rise and mistake that for being normal.

Doing so, the trader can better define their risk and profits and actually maximize their profits not needing the stock to keep reaching new highs.

If the stock falls, they don’t lose as much. And they might believe that a continuation of “right tail” outcomes isn’t likely so they trade off that upside for selling expensive premium to yield a better reward/risk ratio for the trade.

The Logic and Result

In this scenario, the stock enters a period of consolidation, chopping sideways for two weeks as the market consolidates the recent run-up.

The Trend Follower

The trader who bought the dip based on the moving averages gets frustrated.

The Short Seller

The trader who shorted too early sweats every minor lurch upward, facing undefined risk.

Remember that momentum has been shown to be a powerful source of return over decades. Shorting in many cases simply isn’t good risk/reward, even in cases where the stock is clearly overvalued.

Even in such cases, the revenue and earnings from the company won’t be known for years anyway, so valuation is generally not a great standalone short thesis.

The Intuitive Covered Premium Seller

This trader wins in this case.

As the stock struggles and fails to break out, “theta” (time decay) erodes the value of the options they sold.

They extracted cash from the market’s hesitation.

They used their “feel” for buyer exhaustion to monetize the stagnation, turning choppier movement into a profitable income stream.

At the same time, selling covered calls is like a balancing act.

You don’t want the stock to fall too much because then you’re losing money in excess of your premium (and the premiums at your previous strike price are no longer as valuable because they’re further away).

And you don’t want the stock to rise too much because then you’re just leaving money on the table relative to just owning it outright.

Covered calls are essentially short vol positions + a positive delta component.

And even if you’re right, a second-order effect of your success often means that implied volatilities are now lower, which means if you want to replicate the trade, you’re getting paid less for doing so or having to rebuy at a higher price.

The Line Between Intuition and Impulse

Gut feeling shares a dangerous border with pure emotion.

The most critical skill for a discretionary trader is distinguishing between a subconscious pattern match (edge) and a psychological reaction that’s not grounded in any type of edge (error).

The Trap: Anxiety vs. Insight

The primary difference between intuition and impulse is the emotional “temperature.”

True intuition is usually cold and detached. It’s an observation: “The market rally looks weak because the bids are thinning out and there’s little selling.”

Impulse, on the other hand, is hot and urgent.

It’s often rooted in fear: “I am scared the market will fall and wipe out my gains.”

Or greed: “This has gone up a lot and my cautiousness is just causing me to miss out.”

If your “gut feeling” is accompanied by anything physiological (most notably your mood changing), it’s likely not the thing you’re aiming for; it’s anxiety.

Confirmation Bias: The Echo Chamber

The “feel” of the market is easily corrupted by what we want to happen.

Even 75% of professional traders and investors admit they fall prey to confirmation bias.

Even simple things like liking or disliking a president/national leader can predispose people to whether they are positive or negative on the country’s stock market.

If you’re long a stock, your brain is commonly wired to filter out bearish data. You might be less willing to accept that a growth story isn’t as likely as management and sell-side research is portraying.

Confirmation bias can masquerade as market sense. To combat this, there are certain mental exercises you can perform.

One is the “Neutral Test”: If you had zero money in the trade right now, would you buy it at this price? If the answer is no, then you might be biased to what you already own.

The “Revenge” Signal

The most destructive false intuition occurs immediately after a loss.

When a trader gets stopped out, for example, they often feel a sudden, overwhelming conviction that “it has to bounce now.” This is the Gambler’s Fallacy.

This “feeling” is not based on market mechanics, but a type of psychological defense mechanism, a desperate desire to get your money back.

Acting on this revenge impulse at the most extreme turns a manageable loss into a disaster that’s impossible to recover from.

How to Train Your Intuition

Intuition is a muscle that have to be exercised and calibrated. You can’t rely on your gut until you’ve proven that your gut knows what it’s talking about.

For beginning traders, that’s hard because they simply don’t know enough to know what they don’t know.

Here is how to turn vague feelings into a concrete edge.

Paper Trading the “Gut” (Or Doing It Small)

Before risking real capital on a hunch, you must determine if what you think actually works.

Allocate a separate, small account (or use a paper trading simulator) dedicated exclusively to these discretionary trades.

In this sandbox, you’re allowed to violate your rules if you have a strong feeling.

For example, in your main account you might own a mix of stocks, bonds, and gold/commodities.

Then your separate account is you actively trading.

Track these trades separately from your main system.

After enough of a sample size (whether that’s time or trades), look at the data.

If your “gut trades” are losing money relative to your baseline, you’re either not operating with any kind of edge or need to raise your skill level to get there.

If they are profitable, you perhaps have empirical proof that your subconscious pattern recognition is valid.

The “Sniff Test”

The safest way to integrate intuition is to use it as a filter rather than a trigger.

Don’t enter a trade solely because you “feel like it.”

Instead, let whatever your base system is to provide the core of what you do, and use your intuition to validate it.

If a systematic trader has an algorithm that flashes a “Buy” signal, but the price action looks sluggish and your gut says “something doesn’t seem right,” stand aside.

There could be some type of criteria that’s not reflected yet.

If the algorithm says “Buy” and your intuition also agrees, that’s the idea.

Used this way, intuition acts as a risk management layer. It can keep you out of setups that might be technically valid but are contextually poor.

Conclusion

Intuition is a luxury earned through previous and ongoing success in trading, not a shortcut for beginners.

You can’t trade by feel on Day 1; you have to pay your tuition to the market to build the necessary subconscious database.

Ultimately, you can do both – namely, relying on a data-driven process to identify the setup, but trust seasoned intuition to gauge the its quality.

The discretionary or systematic process finds what to do, but the human decides when to pull the trigger. Or alternatively, intuition decides where to explore and a data-driven process ultimately identifies the trades.

Master trading as an evidence-based domain first, so your gut knows exactly when to differ.