The Trade and Economic War Shaping US-China Relations

In our US-China relations overview article, we discussed that the two countries are entering a classic case of one power coming up to challenge an existing power. That’s naturally spilling over into “wars” or conflicts of various sorts. A trade and economic war is among them.

In addition to the trade and economic war, we have other types of conflicts.

There are five main types. We are covering them sequentially:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

These conflicts will have big implications for capital flows and capital markets in the decades to come.

Even shorter-term traders could find it useful to understand where we are and what to expect going forward to develop a broader perspective, see the world in a larger context, and avoid “surprises” that could prove costly.

Most of the big events that may surprise you in your trading career (e.g., asset bubbles, debt busts, big currency devaluations) are things that have happened in other lifetimes and in other societies and occur more or less in a logical progression. Even when they are things that are very different from what we have experienced or may extrapolate from current conditions.

The developmental arc

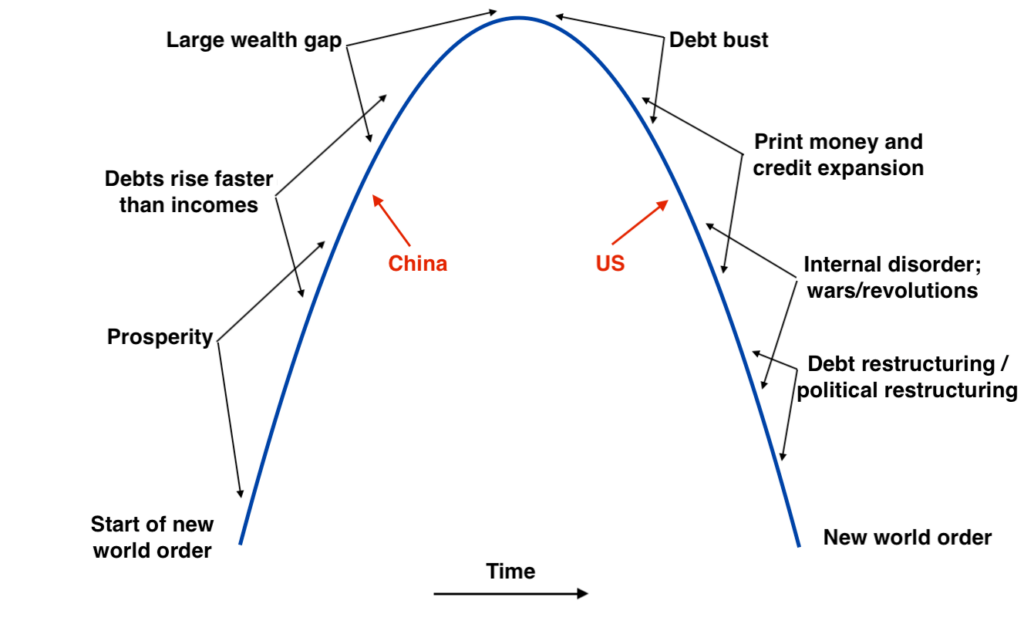

To put things in greater context, empires tend to rise and fall in a cycle.

The success of individual countries revolves around bettering its capabilities in the necessary areas without producing the excesses that make them internally and externally vulnerable to declines.

Most countries and empires that rise to the top globally (e.g., the US now) or in their sphere of the world (e.g. the Roman Empire long ago) tend to maintain this power for only short periods of time. For the most successful, that has meant two or three centuries. No empire has done it forever.

The US has been the top superpower since the end of World War II in 1945. This had big implications for capital markets.

The US dollar was installed as the world’s top reserve currency. That gave it the capacity to borrow a lot cheaply, so it helped the US derive an income effect from it. GDP per capita was about 20 percent higher than other developed countries over that time (e.g., UK, Canada, Australia, Japan) who had lesser reserve currencies.

(Note: There are certain exceptions where per-capita GDP figures are skewed by special events or outliers that have nothing to do with currency reserve status.

For example, there are cases of debt bubbles that temporarily cause GDP per capita to expand beyond what’s sustainable. This is when people are borrowing more than they earn, though it eventually has to be paid back (e.g., Japan in the 1980s and the eventual popping of its bubble in 1989).

There are cases of oil and gas rich nations (e.g., Qatar, Norway, Kuwait, Brunei, UAE), tax havens (Ireland, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Macau, Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland), and microstates (Liechtenstein, Monaco, Luxembourg).)

The stages

Generally speaking, empires go through stages.

The establishment of a world order

An event occurs (i.e., wars/revolutions) where there’s the establishment of a new world order. That leads to a period of calm and prosperity. No one wants to fight the entrenched world power, so there’s a period of relative peace.

Debts rise faster than incomes and productivity

Because of this prosperity (e.g., a reserve currency, which helps borrow cheaply), debts rise faster than incomes. That’s only sustainable up to a point.

Larger wealth gap

Also, as debts rise faster than incomes, you see a larger wealth gap. Those who own assets typically benefit from a period of growth and speculation while the working class doesn’t.

Debt bust

After a point, there’s a debt bust when debts can no longer rise relative to incomes. It can be a classic debt bust where there’s not enough a) money, b) new borrowing capacity, and c) sales of liquid assets to meet the debt servicing requirements brought on through a tightening in credit.

It can also be triggered by other events, like natural disasters, diseases, wars, and so on, that bring on hard economic times.

Print money and expand credit

To rectify the situation, the central bank or central monetary authority wants to print money if it has that ability (i.e., the debts are denominated in its own currency).

It can also use certain tactics if the debts are in local currency.

i) It can change the interest rates to both reduce the size of the debt payments and stimulate credit creation.

ii) It can change the maturities on the debt to spread it out.

If debts can’t be paid, it can write some of them down. But that’s difficult to do in a large quantity because one person’s debts are another person’s assets (i.e., stream of income). So debt restructurings are typically very painful.

If it can take a debt and spread it out over, for example, 20 years and the government can slip in five percent of the loan value each year, it makes it more palatable. It’s a subtle and discreet way of making things okay. (The trade-off is in the devaluation of the money.)

iii) You can also change whose balance sheet it’s on. If important private sector entities run into debt problems, the government can effectively transfer the debt onto its own balance sheet by backstopping it.

The printing of money and new credit expansion to fight a debt bust causes asset prices to rise.

It’s good for those who own financial assets and doesn’t benefit those who don’t to the same extent. That causes more internal disorder and people are inclined not to behave well with each other.

When people don’t act as well with each other, you get more social disruption, which can proceed into civil wars or revolutions.

These often lead to a debt and political restructuring. Sometimes wealth is wiped out or seized. This often comes with greater external conflict and wars with other nations.

When a country is experiencing social and political disruption, that greater vulnerability is sometimes used for gain by another country or countries that recognize this weakness. Eventually there’s a new system or order put into place after the fighting and the cycle begins again.

Russia’s 1917-18 revolution was a classic case of breaking the system and building a new order. This put into place the communist internal order. That system went on before it started to crumble due to inefficient resource allocation. They tried to make big changes within that system in the mid-to-late 1980s, known as perestroika. It failed a few years later in 1991 after 74 years. That was replaced through the new system that Russia has in place now.

The US has had only one civil war in its now multi-century history. It’s also had many severe conflicts and several revolutions that were quite peaceful. The strength of US institutions and governance provides it with great capacity to bend without breaking. But, in general, these are at risk when the individuals within the system don’t respect it more than what they want individually.

The most important thing that drives changes in domestic conditions is how people are with each other. It determines how they will handle the circumstances that they mutually face, and is the primary driver of the outcomes they get.

The general system/order development arc

Many of these periods overlap. For example, it’s sometimes harder to distinguish a period of prosperity from a debt bubble.

A bubble appears like a productivity-generated boom. Financial assets are going up, so it feels good to those who own them. But when debts increase in excess of the productivity gains being produced to service them, it’s an unsustainable trend.

Likewise, in terms of revolutions or civil wars, it’s sometimes hard to mark when exactly they begin, though it’s obvious when you’re deeply in the middle of one. Historians will assign start and end dates, but they are often arbitrary.

For example, the storming of Bastille by a mob on July 14, 1789 is now commonly known as the start of the French Revolution, though no one knew it at the time or how brutal the fight would be going forward. The bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 wasn’t then known as the start of the US Civil War.

Generally speaking, the lines between stages tend to blur together.

Trade and economic war

This article will focus on the trade and economic war and its piece in the puzzle as the US and China work through their conflicts.

Like all conflicts, the trade and economic war can go from being a civil dispute to one that threatens the existence of both sides, depending on how far it’s taken.

The US-China trade war has not been pushed very far. It has included the standard tactics of import restrictions and tariffs that are similar to those seen during similar periods of conflict. The Smoot-Hawley tariffs were a classic case in 1930.

There were trade negotiations from 2017 to 2019 that results in a limited agreement that has only been implemented in a tentative way. Structural disputes between the countries (e.g., treatment of intellectual property, market access, cybersecurity, government subsidies) were naturally untouched.

The negotiation was largely about testing each other’s powers rather than looking toward third-party authorities (such as the World Trade Organization) to resolve their disputes.

All of these conflicts will be fought in a similar way by testing relative powers between the two.

It’s a matter of what form these powers will take and how far the tests of power will go.

The US’s criticisms of the Chinese economy come in three main forms:

i) Theft of intellectual property

The US claims some IP theft is state-sponsored and some believe it to be outside the government’s direct control.

ii) The top-down model of Chinese governance

The Chinese government provides financial resources, guidance, and regulatory benefits to industries and companies that are its most important strategically.

This includes obtaining technologies from foreign companies, particularly as it pertains to tech and other sectors where China wants to be competitive (and needs to be competitive to grow into an international superpower).

iii) China’s intervention and restrictions of market access

China’s government pursues various interventionist practices and policies aimed at restricting market access for certain businesses and imported goods and services. They do this to protect domestic industries. But its opponents argue that it’s unfair.

The US has broadly approached these issues with the intent to change what China is doing.

For example, the US would like China to provide Americans with more access to their markets. The US has tried to force China to move in this direction by closing US markets to China (or making them harder to access).

China won’t admit to taking intellectual property any more than the US will because doing so would reflect poorly globally.

All leaders want to appear like they’re pursuing a noble cause against the opposition that is doing bad things against them. So we hear both sides lob accusations at the other with no admission of the similar things each side is doing.

When the fighting between the two sides becomes more difficult, things that would have previously been considered immoral start to become more justified in the eyes of each.

Leaders increasingly have one version of events that they advertise publicly to help with public relations, and then there’s the reality of what’s being done to get ahead.

The most effective way to inspire public support is for leaders to present their own country as good and moral and the other side as evil and immoral.

It is, however, not easy to rally support if a leader asserts that there are no laws in international wars and conflicts, even if it’s true. Instead, leaders invested in these conflicts will typically shape it as playing by the same rules as the opposition in order to avoid handicapping themselves in a self-imposed way.

How will the trade war end up?

Though trade was a much bigger storyline for the markets in 2018 and 2019, the same issues that led to it will keep popping up.

Since 2020, the market has obviously shifted its focus to the Covid-19 pandemic and the liquidity programs that came out of that.

But trade is still very much a piece of the puzzle with its influence on capital flows.

We have probably seen the best trade agreement we’re going to get. The probability that the trade conflict will get better is less than the odds that it’ll get worse.

Tariff changes may be in store, but it’s likely to only change the course of the conflict on the margins.

Both the US and China are in different parts of their developmental arcs and those forces will play themselves out in the ways they’re likely.

Yet both political parties in Washington take a more aggressive stance toward China. It’s a matter of degree, the expression of this stance, and the response of China to the actions the US take. This is an unknown.

The ways in which the trade war could get worse

Historically, trade conflicts are escalated when one country cuts off another from essential imports. This could mean cutting off a non-resource-rich country from crude oil, for example. This occurred when the US cut off oil from Japan, which led to a military war later on.

In the US-China conflict, this could include the US cutting China off from essential technologies and China cutting off the US from strategically important rare earth metals that go into the production of defense systems, engines and turbines, and other technologically-intensive items. It could also include one cutting off China from the essential imports from other countries via its alliances.

We haven’t seen this yet. It’s a possibility and is another unknown. Either way, when one or both sides cut the other off from essential important it represents a major aggravation that could lead into a worse conflict.

Even if this doesn’t happen, each side’s relative competitiveness will collaterally influence the balance of payments of other countries.

Both countries, China especially, are working to dissociate from each other. That could include independent supply chains, independent technology development, and rising overall protectionism.

Going forward, we’ll continue to see both countries become more independent from each other. As China gains in strength and wealth, it will also naturally be less dependent. It will also reduce its dependencies at a faster clip than the US will.