Coronavirus: The Broader Picture in Context

In economies, there are cycles. There are debt cycles, there’s real economic activity, and there’s the money and credit that facilitates spending power to drive the activity and movements in financial asset prices.

In 1944-45, we began a new monetary cycle where the US was put in place as the world’s most dominant power economically, militarily, and technologically. As such, the US dollar has been the world’s main reserve currency since the end of World War II. We also began a debt cycle from that point forward. Central banks create money and credit. The US dollar is created by the Federal Reserve. It controls how much of it is printed and controls how much credit is created in the economy through the various levers it can pull (e.g., adjustment of short-term interest rates, buying and selling of financial assets).

The ability to create money and credit becomes increasingly hard to do as interest rates get closer to zero. Technically you can get negative interest rates and negative longer-term interest rates (i.e., negative bond rates).

But rate and bond markets can only go so far into negative territory. There’s a limitation in how low you can push interest rates to get investors into riskier assets (i.e., to buy assets that will help finance spending). And driving rates into negative territory isn’t necessarily the solution to get lenders and borrowers eager to do business with each other. Negative rates make cash a little less attractive, but not much.

Savers still need to save and need liquid sources of financial protection, and lenders and borrowers will still be cautious with each other when the economy slows. So, the effect of negative rates doesn’t have the same type of stimulatory effect on economic growth as it would if rates went down by the same amount when rates are positive.

Once interest rates hit zero – or the effective lower bound – as they did during the early 1930s, 2008, and 2020, central banks have to move to a secondary form of monetary policy to buy financial assets to also lower longer-term interest rates and not just short-term interest rates.

If asset buying is out of room because those spreads are also close to zero, then central banks need to move to a third form of monetary policy centered around coordination with fiscal policy. There are various ways to do this that run on a spectrum – from who gets the money and credit (public sector, private sector, or both) and how directly or indirectly it’s given.

The 2020 downturn came because of a public health pandemic. But that was just a trigger. It could have been anything. Whether it comes because of a virus or any other reason, it came during a time at which the central bank had a limited ability to stimulate the economy.

Each individual, each company, and each country has a certain amount of income and expenses, and a balance sheet with a certain amount of debt and a certain amount of savings, either liquid (cash and cash-like securities) or in less liquid forms, such as physical possessions. (Most wealth is illiquid.)

When income falls to a point where it’s below the expenses, then they worsen their balance sheet by digging into their savings or taking on more debt.

There was a fall in income and many individuals, corporations, and countries don’t have adequate savings to cover that.

Even if the virus never comes back, there’s still an amount of financial damage that will last for a long time with a lasting drop in incomes and a worse-off balance sheet.

The world’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, because it’s in the privileged position of having the world’s top reserve currency, has created a lot of money and helped stimulate credit creation, and that’s going heavily to Americans and American companies. And naturally this process is going imprecisely because they had to move quickly.

This means unprecedented amounts of government debt creation (borrowed money) to fill in the gaps of lost income and damaged savings and overall balance sheets.

It’s analogous to March 1933, when President Franklin Roosevelt took the US off the gold standard so money could be created freely to help plug funding gaps in the economy.

Similarly to today’s situation, wealth gaps were high, which meant political gaps were wider than normal and there’s political infighting over how the wealth pie should be divided.

And we’ve gone through that cycle throughout time having to do with prosperity and dealing with difficult times.

In every country, there are income and balance sheet gaps. Sixty to seventy percent of international financial transactions and the storing of wealth is in US dollars. So the US doesn’t quite have a monopoly on the international financial system, but it is very influential.

Europe has a central bank, but it’s quite a bit smaller than the US Federal Reserve, as does England and Japan (and Switzerland, Canada, and the developed Oceania countries), which are smaller than the ECB.

China is the world’s second-largest economy, but the yuan (also known as the renminbi) is not much of a reserve currency, given is has very little share of its currency involved in how wealth is stored globally. But the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) will take care of China’s problems domestically.

Overall, many things internationally have to be bought in dollars. And the production of dollars that the Fed is doing to help with the crisis is largely going to Americans.

Those who have financial gaps outside the US (78 percent of all global economic activity occurs outside the US), often in dollars, may not be able to service them.

About $60 trillion in debt is owed in debt by non-Americans, or about 3x US GDP. They need dollars, but it’s difficult for them to get dollars to pay that back. It’s even worse for those who earn their incomes in domestic currency yet have a lot of their obligations in dollars, especially if their domestic currency went down relative to the dollar (as most did during the coronavirus crash). In such cases, it’s like seeing a rise in interest rates and your debt burdens become compounded.

Europe will have to go through its own process of creating euros and Japan and China creating domestic currency through their own central banks. These countries also have savings in the form of reserves to help manage this process.

But most of the rest of the world doesn’t have a reserve currency, has difficulty borrowing material amounts of money and will effectively have to look toward its own balance sheet. For some countries, based on their overall levels of savings, if they have savings, they’ll have to draw on those. And some of them will run out of those savings.

This is true for even the rich countries, such as the oil and gas exporters, some of which have higher or at least comparable per-capital incomes to the US (e.g., Qatar, Norway, Kuwait, Brunei, UAE).

Their revenues, because of the demand-related crash, are a lot less than their expenses. Then beyond that they have savings (in some cases, substantial savings) and they’re going to have to draw that down. A lot of the world will need to have a backstop to help them through this crisis.

The primary global “lender of last resort” monetary support mechanism is the IMF. The IMF has approximately $1 trillion in assets. Now there’s a debate in terms of how much money should be put out in terms of helping out the major countries (i.e., G-20 countries) and how much to support everybody else. And the amount of support is likely to be inadequate.

These countries needing support have their own central banks. Some have pegged currency regimes, which undermines what they can do. However, they can always change these fixed exchange rate regimes if necessary, and inevitably due when the economic fundamentals force them to.

The issue is that in emerging markets their currencies are not widely accepted or desired internationally by central banks, sovereign wealth funds, or private investors as a store of wealth or a source of savings that brings with it the expectation of higher future purchasing power. And they’re not widely accepted or desired internationally as a means of international trade and payment invoicing.

So, when they print those currencies that diminishes the value of it because there’s not much demand. So, it’s going to be very difficult for those countries, especially those that owe a lot of money to the rest of the world (i.e., debtor countries).

Should we expect inflation?

There are two kinds of inflation. There’s goods and services inflation, which means the demand for something in an economy exceeds its supply and its price goes up. Labor inflation is usually the type of inflation that central banks seek to corral at the end of typical business cycles, hiking interest rates, and causing a downturn in output until inflation is back under control. Then the central bank eases interest rates and the cycle starts again.

But that’s not the kind of inflation that’s been relevant to the business cycles of the US or other developed economies since the financial crisis.

Instead we’ve had monetary inflation, or rises in financial asset prices even when the pickup in goods and services activity has been low. There’s a complement between the two (real economy and financial economy). As financial asset prices rise, that feeds into the real economy with better creditworthiness among households and corporations and lower borrowing costs.

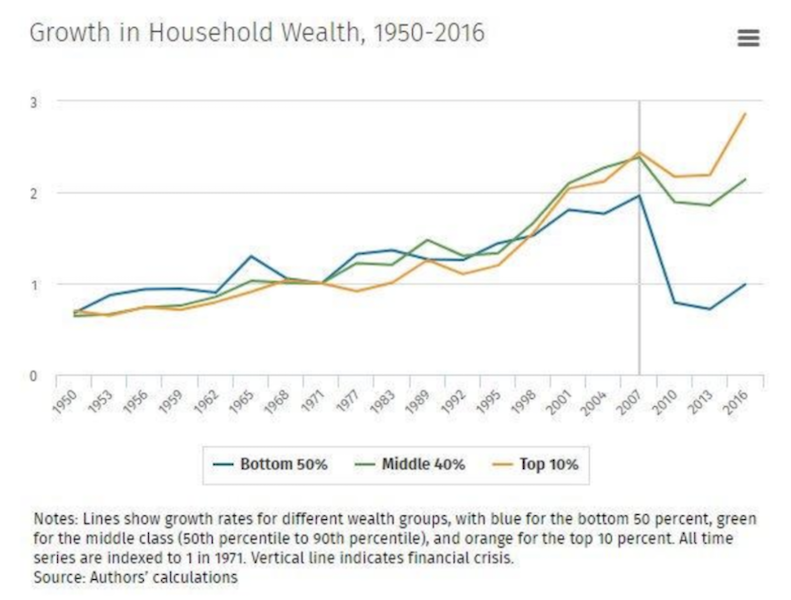

But there’s been a dispersion. Financial wealth has grown a lot more than goods and services output. It’s also fueled the wealth gaps between those who own financial assets (those who are wealthier) and those who don’t own financial assets (those who have little wealth). That’s bled into political movements and greater polarity between the left and the right.

Moreover, it’s easy to produce financial wealth because printing money is easier than the creation of goods and services.

What inflation takes place (real economy inflation vs. financial asset inflation) will depend on where you are in the world.

In the US, Europe, and Japan (broadly, the developed world), all this money creation is simply filling gaps in incomes and balance sheets. That’s not a process that causes inflation. It’s simply negating deflation by providing a monetary offset.

But when it comes to other countries without reserve currencies, they’re going to have a harder time.

They’ll have the creation of their own money by their central banks, but the demand for it will be lacking.

Has the US stimulated enough through monetary and fiscal policy been enough to begin the crisis recovery (or at least set the stage for such)?

The aggregate losses in the United States is about $5 trillion from households and companies. Global losses are somewhere close to $25 trillion.

And it’s not just about creating money of this amount to nominally cover the losses. It has to go to the right entities and in the right amounts

Currently, based on what’s been done, it’s still a bit short in the US. Globally it’s significantly short, particularly when the “printing” capacities globally are much more limited due to the lack of demand for their currencies and Federal Reserve programs are designed chiefly to help Americans.

Increasingly through time, the world becomes more intertwined financially, so these income and balance sheet problems matter even if they’re not domestic. And this would be true even if the virus played no role in the future, even though there’s a significant likelihood that it will. (But that’s an entirely different topic.)

And there are also the elements of how targeted it is and how fast it gets there (e.g., companies needing to make payroll by a certain date). And in terms of that – getting it where it needs to go and the speed – hasn’t been perfect.

The wealth gaps driving the political gaps

Almost every time there’s an expansion there’s a simultaneous expansion in the wealth gap. When the expansion ends and there’s a downturn, there’s some distribution of wealth. These gaps tend to be highest when the power to lower interest rates is out of room. Then central banks buy financial assets and benefit those who have them in a disproportionate way to those who don’t.

That feeds into populism of the left and populism of the right and there are higher levels of social tensions. There’s a lot more conflict over how to divide the economic pie. This was true in the 1930-40 period (after a debt crisis in which interest rates hits zero) and is true today after a similar type of crisis in 2008 and again in 2020.

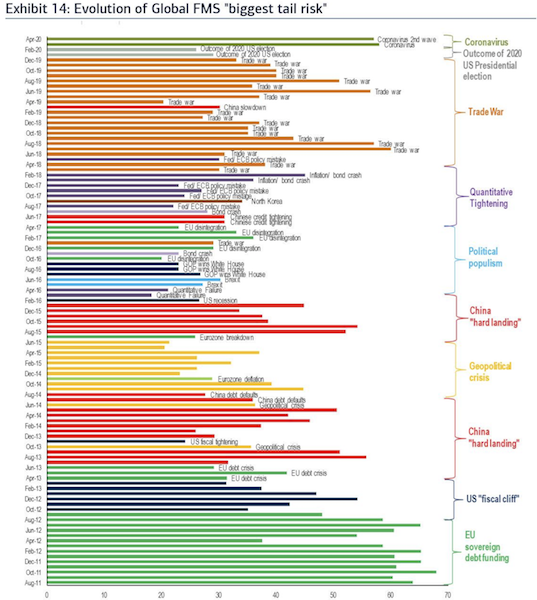

Because who has their hands on the levers of power is important and because the distribution in policy outcomes is wider during these times, this tends to result in great market volatility given markets discount in these distributions. Elections inevitably impact asset prices.

And both 2008 and 2020 were major political years, with presidential elections in the United States. Before the coronavirus, the outcome of the 2020 presidential election was top of mind for investors.

(Source: BofA Global Managers Survey)

The virus-related recovery took its place by late February, but is still an important current determinant of the discounting process for markets (e.g., discounting outcomes based on poll numbers).

So, there’s going to be arguing about how to divide up the wealth through spending programs and taxation plans.

Usually during a downturn, more move left on the political spectrum and there are more calls to put higher taxes on those who have the highest incomes and wealth.

The conflict itself can cause greater swings away from the capitalist system, which has led to the popularity of politicians like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Jeremy Corbyn, whose policies and general campaign messages take aim at many parts of the profit-making system that dictates much of the process of how economies are run and fundamentally based off of.

Investments coming out of the pandemic?

When it comes to where to put your money coming out of the pandemic, it first starts with going back to who has the incomes and balance sheets available to invest. During the downturn, this has gotten damaged.

So when looking at where to invest, a lot will depend on who gets the monetary and credit support from the government and its various programs.

For example, take the case of airlines and cruise ship operators. How they do going forward will depend on not just how fast the economy comes back and the sustainability of that process, but whether they get the monetary resources to weather the downturn.

A lot of people have claims on goods and services through financial assets – i.e., the way the financial economy ties in with the real economy. Those financial assets are only worth what they’re purportedly worth if the cash flows are available.

Due to this crisis, savings rates will rise among individuals and companies. After this period, it’s natural for all entities to want greater safety. During a longstanding bull market, it’s easy to get accustomed to and extrapolate current conditions forward and take greater risks. The bad times of the past fade from memory and risks are underestimated.

We’re also moving away from a world where the most efficient producers get the work and then higher-cost countries would buy these goods. From this process, companies benefited from higher margins and profits and individuals benefited from cheaper products that were imported. Those in the US and other developed market countries enjoy all types of products that were made in emerging markets where the labor is cheaper and much more competitive on an output-per-hour basis than more expensive domestic workers.

That’s now changing. Instead of a more efficient, interconnected world that had a level of specialization, there will be some countries pulling back and wanting to do more of their production independently. There’s the trade-off of efficiency versus self-sufficiency.

The self-sufficiency element has to do with not relying on certain parts of the world to do things for you, especially when there’s a level of conflict. It’s a different geopolitical world and a growing desire to not be vulnerable, or a greater recognition of the vulnerability that exists being interdependent.

When the US buys certain things from China, there’s going to be more of a desire to produce those things internally. That’s going to make those things produced less efficiently in terms of output per hour, leading to things like higher prices with respect to certain goods, but there’s going to be a greater intention of doing that believing the trade-off is worth it.

China will continue to rise in influence along economic, military, and technological lines. This will form a more bi-polar or multi-polar world. This could produce an increasingly pronounced bifurcation in the global economy. For example, both economies could have separate supply chains and be in virtual competition over developing future technologies independently (especially those in 5G, artificial intelligence chips, information and data management, and quantum computing).

Rather than that being resolved soon through trade traces and bilateral trade agreements and whatnot, these various economic and geopolitical disputes (e.g., over Taiwan’s reunification with mainland China, global spheres of influence) will be with us for decades to come.

Final Thoughts

This restructuring process from the coronavirus will go on for the next 2-5 years. That’s a long time, but over the scope of history it’ll be like a blip in the radar. The human capacity to adapt and invent and come out of things better and more advanced than it was before is enormous.

These periods like 1929-1933, 2008-09, and today’s current situation are painful periods, but relatively short restructurings.

What will the future going forward look like? It’s increasingly about data and digital technologies.

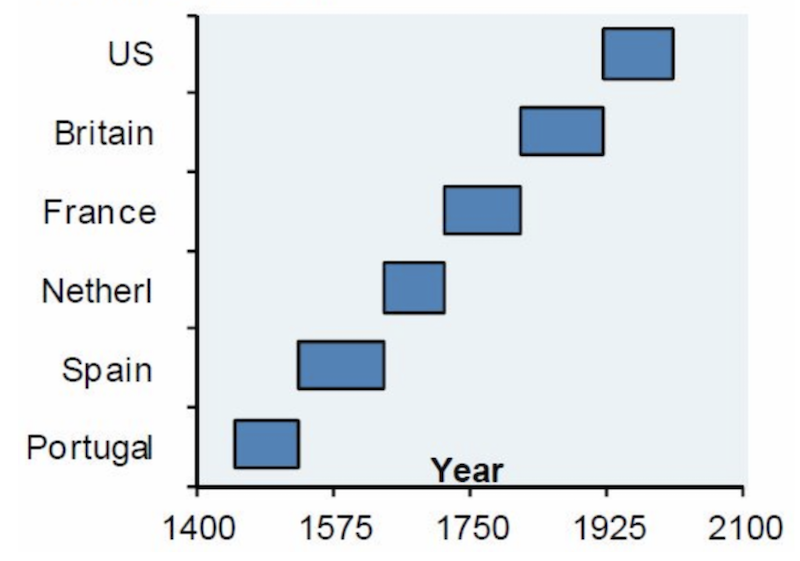

In previous centuries, the economy was agriculturally based and wealth primarily meant owning land.

Then it switched more toward manufacturing and producing goods that could be sold all over. First, selling domestically, then internationally through trade routes, which heavily started with the Dutch empire and then the British empire. And that production was what wealth was.

It takes a robust military to protect those trade routes and overseas territories and interests. Empires inevitably overextend themselves, become heavily indebted and get overtaken by new empires, who eventually have the same problems. Being this top power conveys advantages, such as having the world’s top reserve currency of which an income effect is derived (can borrow more cheaply).

But reserve currency status doesn’t last, though it typically remains for several generations (75-150 years).

Since the late-1800s, developed economies have gradually changed from production to services. Agriculture became an even smaller part of the economy (e.g., more consolidated among fewer players) as did manufacturing as it increasingly became the old economy. Other developing economies took over more of those jobs.

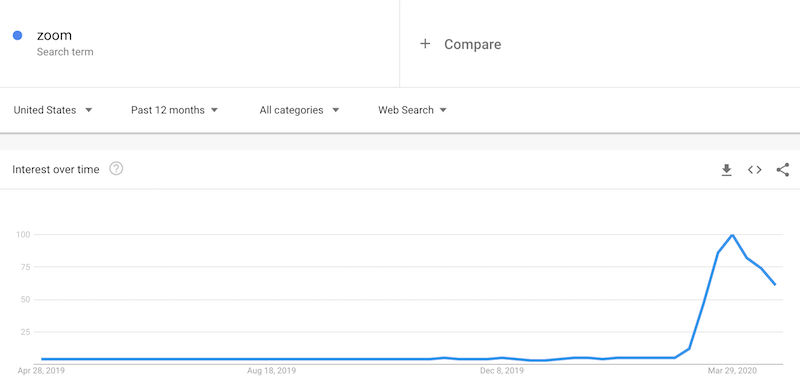

And now we’re increasingly moving toward digital technologies. Interacting digitally instead of in-person, even more so than before, has been a common theme of the social distancing process. That will continue. Technologies that improve productivity and efficiency in this regard and all of its various applications will be treasured, and there will be users and builders of this.

Some sectors are going through clear structural changes. Many of those changes will end up becoming permanent. We see the demand in sectors like e-commerce, electronic banking and tele-banking, and telemedicine taking off during the crisis. This is true in particularly for the under-40 crowd with respect to the former two and among rural populations.

Zoom’s PR has gone through the roof as teleconferencing picks up, both for remote work and to do lessons while schools are closed down. Below is the Google Trends for Zoom over the past year.

Online education is seeing a boost. Telemedicine was already a common technological trend, but it’s adoption is being accelerated further, particularly for older populations as there’s now more of an incentive to take up this technology.

Work from home will become more in demand. Many companies are or have been against work from home arrangements fearing people will “mail it in” and their productivity will be unacceptably low. Some companies, through the necessary arrangements that had to be setup to get work done during the coronavirus crisis, will see that productivity has been stable. This is likely to lead to a more positive view on remote work policies. In turn, this could also reduce commuter traffic, particularly in notoriously congested cities.

Could less time commuting enhance economic productivity? Will demand for things like, for example, gasoline and auto parts decline? These are the types of microeconomic questions investors will need to answer as trends emerge coming out of this crisis.

Naturally, there will be a shift involved in the supply and demand of skills and some will be disadvantaged by this shift. Many jobs will be lost, but new opportunities and technologies will be developed to drive the evolution of society, and in turn create more jobs than were lost on net.

To use an old example, in 1812, mobs of manual laborers smashed and burned a textile mill near Nottingham, England, as a means of protesting its use of mechanized looms. They feared these new instruments would put them out of work. Inspired by Ned Ludd, an earlier (and perhaps make-believe or misattribution, as the historical record isn’t clear) critic of technology, these protesters became known as Luddites, which still remains a synonym for people who oppose industrialization and technological progress. Nonetheless, over the ensuing decades, England created more jobs than any other nation ever had despite its factories becoming more mechanized.

We have enough resources, creativity, and inventiveness to get through the coronavirus downturn. It’s a matter of whether the conflicts are going to be handled well in a bipartisan way, or are they going to be handled poorly, with infighting between the two sides, which are more polarized than normal.