The Market’s Biggest Tail Risk

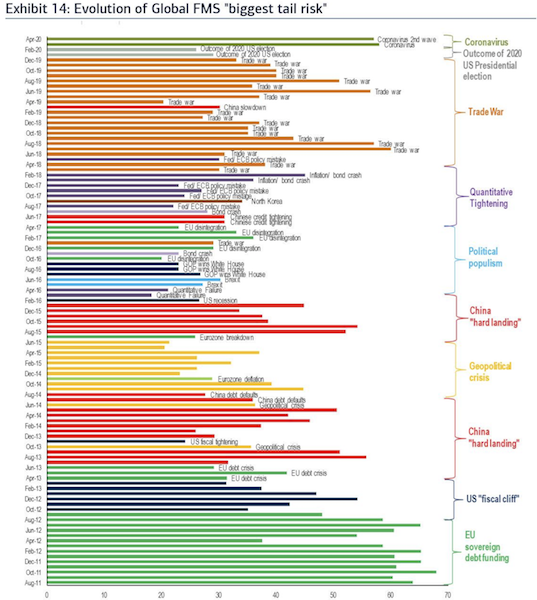

Each month, Bank of America takes a ‘Global Managers Survey’ to obtain opinions on various matters concerning the market. The most popular is the question on the biggest tail risk in the financial markets.

Graphically, it’s displayed month by month and taken at the beginning of each month.

(Source: BofA Global Fund Manager Survey)

At the beginning of February, the outcome of the 2020 US presidential election was still at the top of most traders’ minds. Intel about the novel coronavirus started in December and a known factor in the US by early January.

By late January, the commonly applied heuristic was the SARS epidemic from 2003. However, indiscriminate application of any given prior episode isn’t sound given the nature of it typically differs. If you use the past to determine the future but the future is different from the past, then you’re going to run into issues.

While SARS saw equity markets fall about 10 percent in most parts of the developed world, the coronavirus was much more contagious and virulent. That, of course, led to widespread lockdowns and much in the way of lost economic activity, leading to a downturn worse than that of 2008.

The virus-related risks remained underestimated at the same time volatility was low and interest rates were low relative to the prospective return on equity. This encouraged leveraging up to obtain the desired return on equity. Then the economy did a 180 and caught almost everybody out of position.

The top perceived risk quickly went from – what happens to risk assets if either Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren becomes president? – to an unexpected pandemic, a tail risk whose possibility is never priced in. The pandemic should have been perceived as the bigger tail risk in February (a month earlier), but most believed it would pass through.

By the beginning of March, nearly two weeks after the stock market topped and already dropped 25 percent peak to trough, naturally the coronavirus became the biggest tail risk. The consensus was the highest since July 2018 when the ‘trade war’ was at the forefront of the markets and will be the most enduring surveyed risk since the EU sovereign debt crisis in 2011-12.

Coronavirus’s second wave is the biggest tail risk

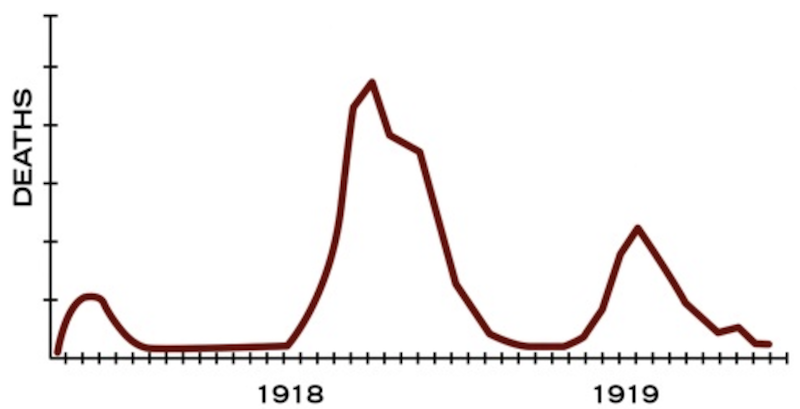

By April’s survey, the risk moved away from not just the coronavirus itself, but toward a potential second wave.

In the case of the 1918 pandemic, the first wave was relatively brief in comparison to the large second wave. Even after that, a third wave came that was 2x-3x the size of the first. Then it vanished.

(Source: cdc.gov)

While the stock market is up 30 percent from the bottom, and many states are working on timelines to open back up, all those plans could be thrown into disarray if another wave comes.

Most business owners are looking forward to restarting the economy and their own companies. But it’s not likely to simply be a return to normality. Restarts are likely to be partial and fragile. Customers and employees in certain types of businesses may be subject to temperature checks and increased monitoring. We could go through a cycle of restarts and controls until a vaccine hits the market. That’s likely to come in the second half of 2021.

Digging deeper into the ‘biggest rail risk’ question

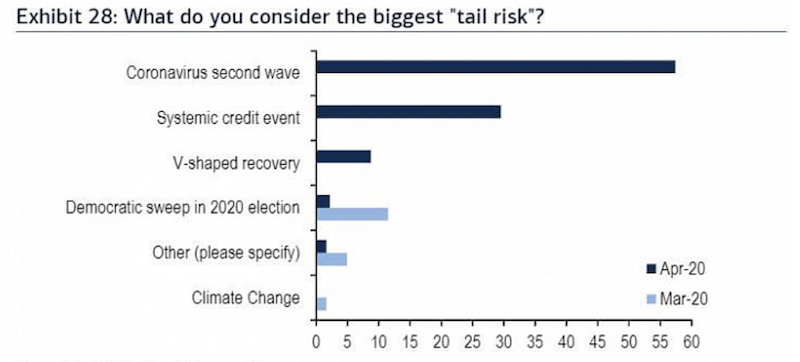

So we know that a coronavirus second wave is the biggest tail risk assessed by Bank of America’s institutional clients with nearly 60 percent of the vote.

What risk came in second and third, and so on?

At 30 percent came a systemic credit event, followed by a ‘V-shaped’ recovery at 9 percent.

(Source: BofA)

Why is a V-shaped recovery – a good thing – perceived as a tail risk?

If there’s a swift recovery, it will incentivize the Federal Reserve to pull back on their stimulus measures. The level of support the Fed is providing to the economy is being extrapolated forward by market participants, as is naturally the case, and has been a big part of the market’s return. It’s retraced about half of its lost gains in the US (the move from 3,390 down to 2,180 in the S&P 500).

If the series of stimulus measures – credit guarantees, lending programs, quantitative easing, zero percent interest rates – is withdrawn, that’ll take some of the unprecedented amount of liquidity out of the financial system and cause the market to drop.

The Fed will need to pull back on its measures carefully, as markets price in what they expect and markets matter a lot for policymaking as they provide the money and credit that feed into spending in the real economy.

Good things for economies can be bad things for markets. In February 2018, when short volatility positioning was very high, wage growth numbers were higher than anticipated (a good thing) when non-farm payrolls were released, the well-known data point released on the first Friday of each month.

But this was interpreted by the market that the Fed would hike interest rates faster than was discounted into the curve. This term structure of interest rates is baked into the prices of all financial assets. When this goes higher, holding all else equal, the prices of financial assets fall due to the present value effect. So, we saw a little bit of a correction in asset prices.

(Source: Trading View)

Fourth on the list is the idea of what happens to asset prices if Democrats have great results in the 2020 elections. Democrats are perceived as less market friendly, especially the populist candidates with less centrist policies.

What type of process are investors most worried about?

Coronavirus is a type of notional risk. For that to translate over into markets then it has to be thought of in terms of what processes or products does that affect.

There’s the economic risk of lost productivity and lost economic activity as people shelter and reduce movement. That then bleeds into credit markets as individuals, businesses, and governments (usually emerging market governments who can’t print money) have difficulty meeting their obligations.

There are always a lot more financial assets (an asset to some and a corresponding liability to somebody else) and obligations than cash available to pay for them.

When there’s a dash for cash, people try to sell assets to come up with it. Governments that have control over this process then need to provide a mix of money printing and credit guarantees to get a floor under the situation.

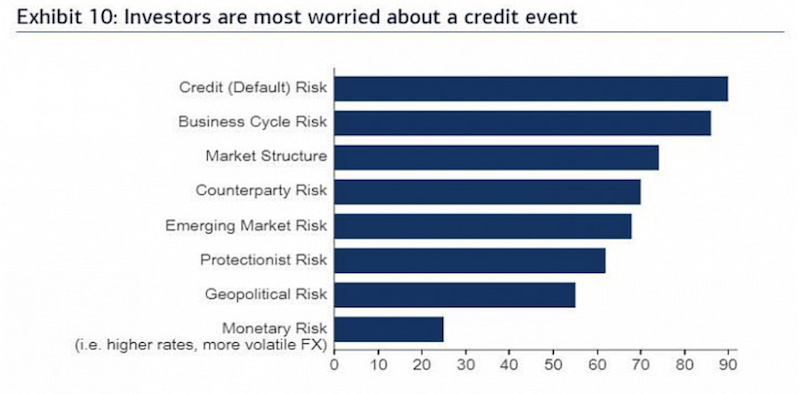

Credit risk

So, credit (default) risk is number one on investor’s minds:

Going into the coronavirus crash, most traders were positioned for the economy to get better, though the economy got materially worse.

Business cycle risk

That’s followed by business cycle risk. The traditional way business cycles end is through the central bank hiking interest rates (usually to fight inflation).

Typically, as unemployment falls and the demand for workers exceeds their supply, the price of labor begins to pick up. This stokes inflation. Monetary policymakers then have a much more acute trade-off balancing growth with this inflationary pressure. It’s hard to get right and sometimes central bankers must choose to corral inflation by hiking rates to get it under control. This causes credit costs to go up in excess of the ability to pay for them and the economy enters a recession. The central bank then eases, once inflation is under control, by lowering interest rates and the cycle repeats itself. That’s what we’re all used to and this cycle typically lasts 5-10 years, though no one cycle is exactly the same.

That’s the normal dynamic that’s been behind other bear markets, notably the drop in asset prices in developed markets and most of the world in Q4’18.

The coronavirus crash has been different. We’re not dealing with the output and inflation trade-off. Rather we’re dealing with what happens when debt is high relative to income and you have limited ability to lower interest rates or buy longer-duration assets to ease policy. Instead, other policy forms have to be worked out, notably fiscal and monetary policy coordination.

When it’s very hard to put a floor under it – namely, pushing nominal interest rates below nominal growth rates – then the contraction keeps on going.

Only after the Fed promised to establish lending facilities, swap lines, and backstop a very wide range of collateral – from not only US Treasury bonds and government-backed mortgage securities, but also corporate credit (including some low-grade bonds), municipal bonds, and even ETFs – did the market bottom.

So, the business cycle risk as it’s typically recognized – inflation and output trade-off – is different this time around. Central banks in 2019 realized they wouldn’t have the ability to normalize interest rates, unless there was an unlikely uncomfortably uptick in inflation. This is also what incentivized the 2019 bull run that finally ended in February 2020 because of the disruption of the coronavirus.

In sum, we’re currently dealing with a “depression” dynamic. While the word “depression” is evocative because it conjures images of Hoovervilles and bread lines, and is used for sensationalized purposes, it fundamentally has to do with the dynamic of an unsustainably high debt burden relative to the current level of output. Rectifying this imbalance involves either writing down the value of the debt and obligations or the central bank “printing” money.

We are not dealing with the normal recession dynamic that central banks control through the adjustment of short-term interest rates.

Market structure risk

Third on the list is market structure. This pertains to the nature of the market participants and who the buyers and sellers are – passive versus active, humans versus machines, central banks versus private institutions – and that entire debate about how it affects liquidity and price discovery.

Even as the nature and decision-making processes (e.g., speed, level of automation) of the market participants has changed over time, the basic dynamic of how these types of cycles play out over time hasn’t changed. What happens when debt servicing is too high relative to income and the type of impact that has on asset prices is a timeless process.

Counterparty risk

Counterparty risk involves those involved in a transaction defaulting on their contractual obligation(s). When 2008 came around, some banks went under, bringing worries that even cash deposited in a bank could be lost if not withdrawn. For investors, it could mean a brokerage ceasing its ability to lend, which would be bad news if you invest using borrowed money. It’s why many institutional investors diversify their accounts among multiple banks.

Counterparty risk hasn’t been anywhere as big of a factor compared to the last downturn because the financial sector has deleveraged relative to where it was in 2007 and 2008.

Emerging market risk

There’s emerging market risk, identified by close to 70 percent of surveyed participants. Emerging markets (broadly considered countries outside the US, developed Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand) accounts for close to 50 percent of all economic output and most of all new output. The oil price collapse has hit exporters particularly hard. Some emerging markets are going through defaults or restructurings (e.g., Argentina, Ecuador, Zambia, Lebanon).

Many countries borrow in dollars with their lower interest rates and better funding availability. But they run into trouble when they experience balance of payments problems, which triggers problems with their currency and difficulty in repaying in a foreign currency that’s increased in value. (See Argentina, Turkey)

The US, developed Europe, and Japan all have reserve currencies and the ability to create their own money to offset the lost economic activity. But emerging market countries are more limited in this capacity, especially if their borrowing is done in a foreign currency. Many debtor emerging market countries, if they do run into debt issues during the crisis, will need to impose austerity measures, which can lead to years or even decades of lost output. This is why having a reserve currency and having the ability to “print money” is such a privilege.

Protectionist risk

Protectionist risk pertains to trade disputes. Markets like “globalism” and free trade as it helps with the more efficient allocation of labor and resources to maximize earnings.

There’s a longstanding issue on this front between the US and China and likely between the US and European Union. While all this is currently on the back-burner, this will be around for a very long time.

There are questions of whether each country should have independent supply lines. Should the goods being produced in China (to export to the US) instead be produced in the US for the sake of independence? There are questions of capital flows. For example, if you’re from China and investing in the US, is that a good idea if there are economic sanctions (and vice versa).

A lot of it comes down to culture. Each country has a different way of handling issues.

For example, big tech and big data is a powerful force in driving innovation and new productivity, and the US and China are the world’s leaders. Whoever is most technologically advanced will tend to be more advanced in most other ways (e.g., militarily, economically). How “big tech” is managed will depend on the culture.

In the US and most of the western world (though mostly US; Europe is not much of a tech pioneer), it’s a bottom-up decision, starting with individuals and companies.

In a place like China, it’s a top-down decision where they collect as much data as possible largely irrespective of privacy concerns so they can make the best decision and achieve the best result for the whole. The US and western democracies largely prize the role of the individual while China emphasizes the role of the “family” or what’s best for the country as a whole. Each system has its pros and cons.

The “trade war” is just one prong in the battle of the US fighting off an ascendant power and this will continue for decades. This isn’t like the US’s trade negotiations with Canada or Mexico where they sign an agreement and everything is “back to normal” (or the notion that it would take a different presidential administration to de-intensify the conflict).

It’s a long-term geopolitical confrontation that’s one block in a larger picture of a rising power coming up to challenge the status quo of the incumbent global economic and military superpower. When it comes to structural concessions that impede China’s long-term goals –e.g., intellectual property, non-tariff barriers such as market access for US companies, government subsidies, coerced tech transfer, cyber-espionage – that simply won’t be agreed upon.

Geopolitical risk

Geopolitical risk is a concern for just over half of survey respondents. This includes US-China relations, but also branches into Russia-Saudi Arabia with their influence on the world’s most important commodity (and how that feeds into global capital flows, currencies, and credit markets), Mideast instability (e.g., Iran), and the concern over North Korea and their nuclear and ballistics program, which has also been pushed to the back-burner.

Monetary risk

Only about one-quarter of investors see monetary matters as a material risk. This includes things like higher interest rates, which would derail a recovery.

But central banks in developed markets will be pinned there for a long time.

Highly indebted societies cannot support high real interest rates. Low real rates are the best way to reduce debt burdens and deficits. The US held rates artificially low before and after WWII resulting in negative real returns for investors. We should expect to be at zero short-term interest rates in the US, EU, and Japan for a long time.

Investors also believe that central banks have good control over their currencies.

But when interest rates are at the lower zero bound and can no longer be lowered and relative interest rates can’t be changed currency volatility needs to pick up. If this isn’t true, then you get economic volatility. This is an issue in the main three global reserve currencies – USD, EUR, JPY – where interest rates are all at zero.

The devaluation of money and what that means for savers and for the handling of future downturns is a big topic in itself. Nobody wants a stronger currency and no country wants to allow one currency to unfairly devalue itself to get a leg up in trade. This can lead to the issue of “currency wars” and other forms of monetary conflict.

This is why many investors diversify a smaller portion of their capital into hard reserve assets like gold and other precious metals that serve as alternative currencies.

Long-term impacts

The San Francisco Federal Reserve recently released a paper studying the long-term economic impacts of pandemics, rather than solely the short-term considerations. Some expect, or at least want to be optimistic about, the aforementioned ‘V-shaped’ recovery, or gaining back lost output in a short period of time.

Through the studies of past pandemic, the authors found longer-run economic consequences associated with these events.

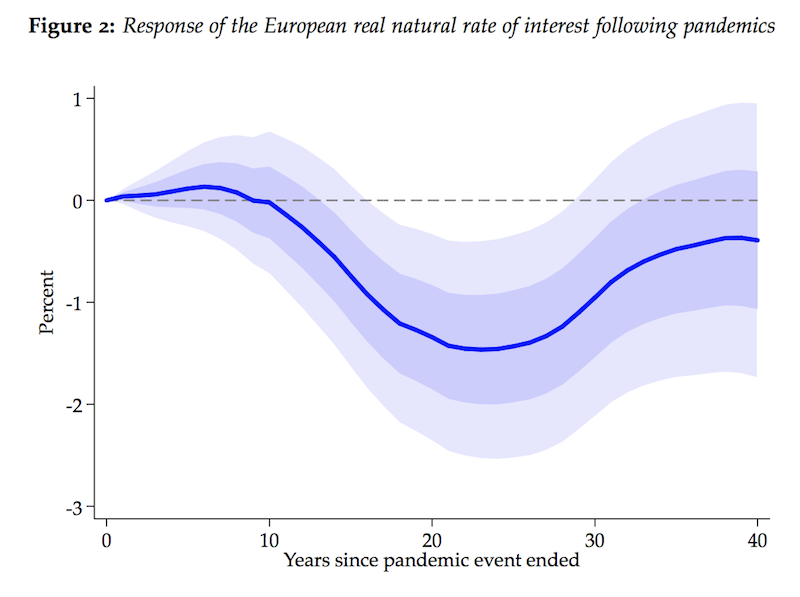

They found that “[s]ignificant macroeconomic after-effects of the pandemics persist for about 40 years, with real rates of return substantially depressed.”

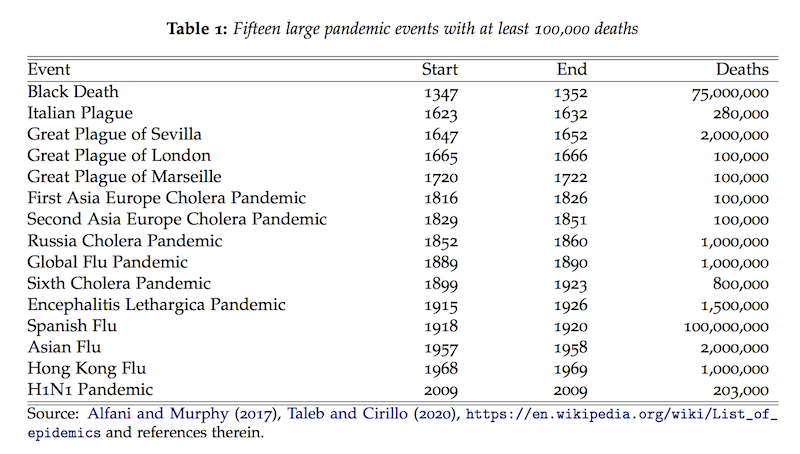

They drew time series data from several pandemics dating back to the Middle Ages to the extent such data was available. They identified fifteen large pandemics with at least 100,000 deaths, starting with the Black Death of the 1300s that killed an estimated 75 million people.

When recessions hit, real interest rates often remain depressed for 5-10 years. But they found that real interest rates remained depressed for up to several decades after the end of the pandemic in an economically and statistically significant way.

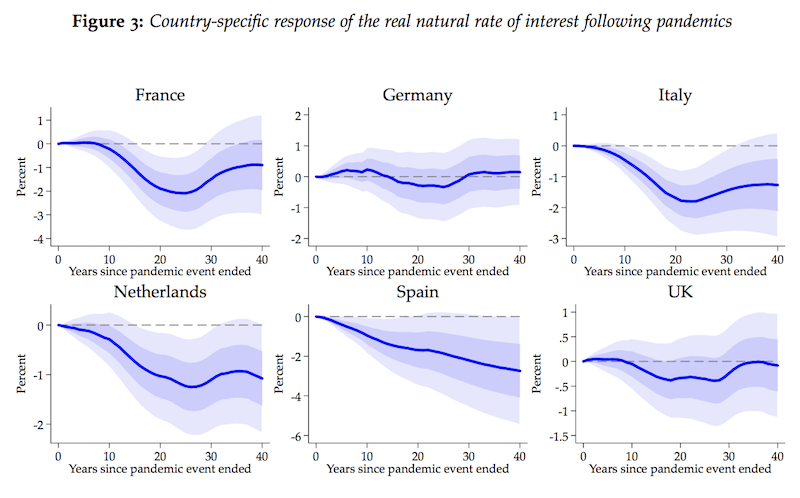

To study differences to see how this general finding held up in different markets, they discerned the effects by different European countries:

Some divergences appear based on the relative exposure of each individual country to the pandemic, the extent of the working labor population, and its degree of industrialization.

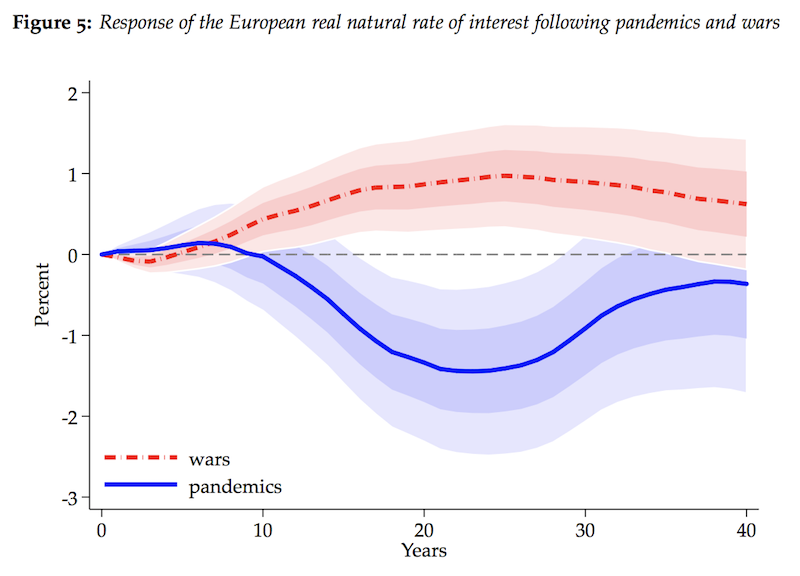

They found the effects of wars to have the opposite effect, where wars increase real interest rates in an economically and statistically significant way and over the same 30-40 year period. Wars consume resources and require debt funding, which could imply higher real interest rates as more capital competes for less money. Capital is also destroyed during wartime environments, following the same supply and crowding out argument. It could also mean higher risk premiums as higher indebtedness means a higher likelihood of default.

If Covid-19 is similar and produces lower real rates of interest than would have been seen otherwise, this is beneficial for governments with fiscal space who can borrow more cheaply. Longer-term sovereign borrowers can also potentially reduce the monetary consequences of the pandemic with lower real interest costs.

Conclusion

Even with the focus of an economic re-opening throughout the developed world, investors consider a future wave of the coronavirus as the biggest tail risk going forward. A vaccine is at least a year away from the peak (April 2020) and any re-openings are likely to be cautious and fitful.

Investors should approach the upcoming 1-2 years as a period of greater than normal risk and volatility with monetary policy out of room in the traditional ways.

Having well-balanced strategic diversification has never been more important and is the way that most traders will be able to sustainably make gains over the long-run.