Fiscal and Monetary Response to Coronavirus

The coronavirus has hit the economy in a way that’s entirely unique from what we’re accustomed to. Instead of recessions associated with overly tight monetary policy or crises brought on from too much debt coming due, a public health scare has shutdown large swaths of the economy. This closed down activity, reduced incomes, made debts and other payments difficult to make, and punctured a big hole in economies and financial markets.

With the passage of the $2.2 trillion CARES Act in the US, the stock market has bottomed for now. In fact, we’re technically in a new bull market with the S&P 500 bottoming at 2,182. (The Great Depression had eight bull markets within the context of a drop of 89 percent in stocks peak to trough.)

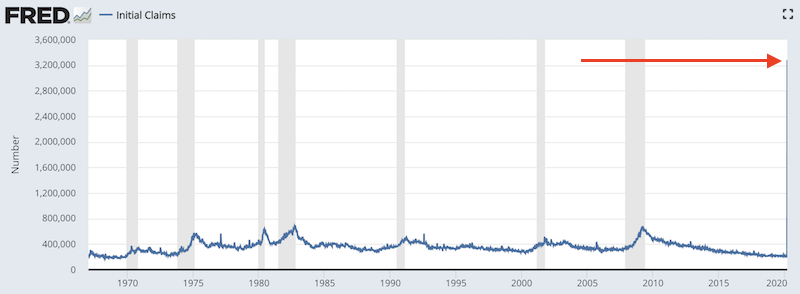

Much has to be repaired. US initial unemployment claims were the highest ever by a large margin. The 3.3 million figure blew the 665k figure at the height of the financial crisis out of the water, including the previous all-time record of 695k in the early 1980s.

(Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration)

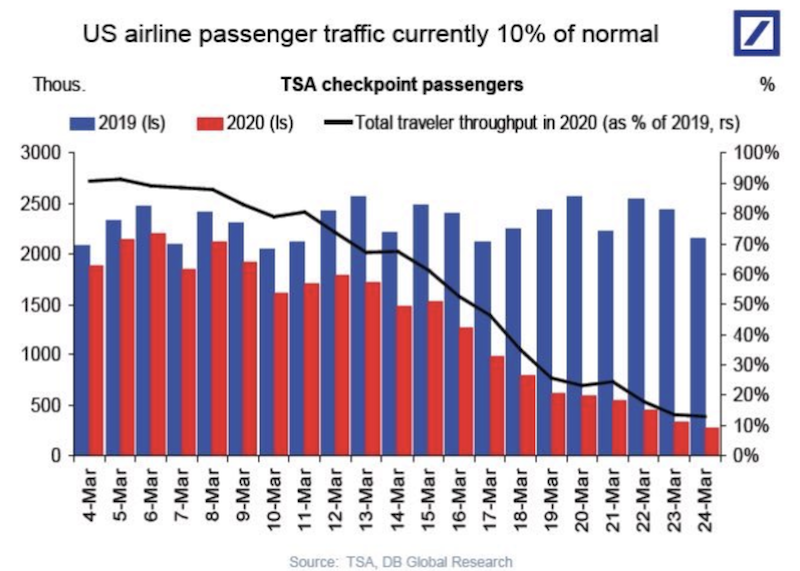

In other data, US airline traffic is currently running at around 10 percent of normal, damaging all the top airline stocks, including American Airlines (AAL), United Airlines (DAL), and Delta Airlines (DAL).

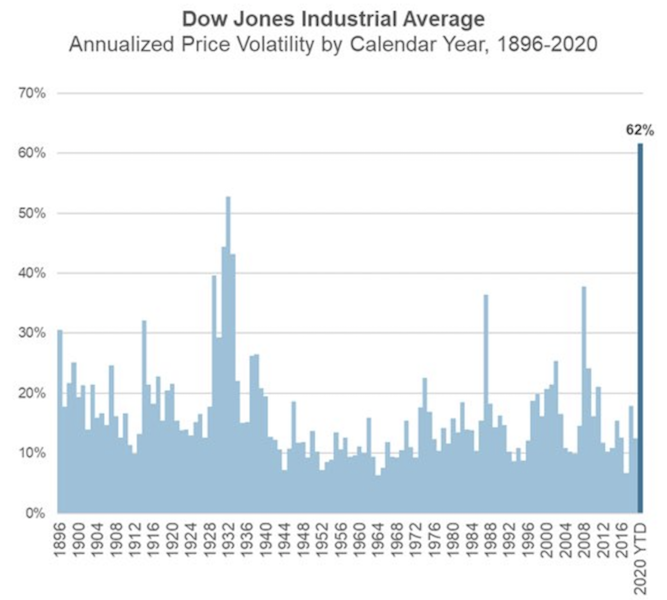

The Dow Jones Industrial Average has seen year-to-date volatility of 62 percent. This dwarfs what was seen during 2008 and any year during the Great Depression (1929 and years immediately after), using data going back to 1896.

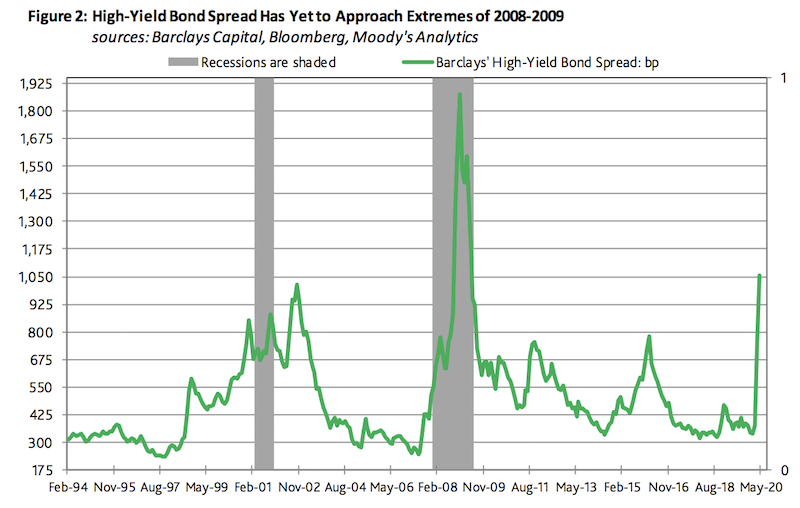

However, one part of the market that hasn’t seized up is the credit market.

In 2008, the government was late in recognizing what was happening. It wasn’t until after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, due to its subprime lending portfolio, that interest rates were finally dropped to zero and programs like quantitative easing (QE) and the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) were started.

The high yield bond spread (extra yield above government debt of similar duration) blew out to about 1,900bps (i.e., nearly 20 percent) in October 2008. Currently, we’re seeing a more modest 1,050bps.

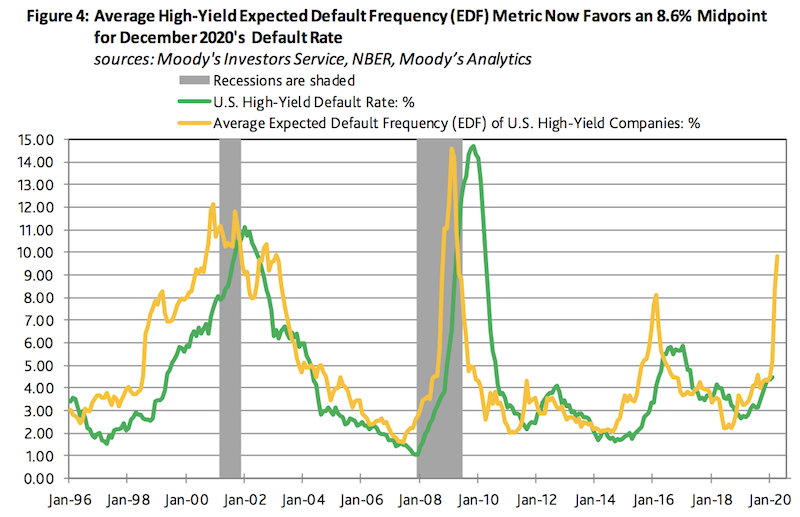

Moody’s expects about a 10 percent default rate from sub-investment grade (i.e., high yield) borrowers.

Fiscal and monetary response to coronavirus

Monetary policy follows this template:

Primary monetary policy: Adjustments of short-term interest rates

Secondary monetary policy: When interest rates hit zero and lowering them is no longer effective, then central banks must buy longer-duration assets, such as government bonds and other government-based securities, to drive corporate and household funding costs lower to stimulate credit creation and help drive asset prices higher. This is commonly known as quantitative easing (QE).

Tertiary forms of monetary policy: This must involve some form of coordination with fiscal policy. In this phase, the central bank must create the money and ensure it is both provided and spent. When nominal interest rates can’t be lowered below nominal growth rates because they’re at the effective lower bound (somewhere around zero percent), then the spending must come up. When the private sector is weak it must come from the public sector. How this is done varies based on who gets the money – public sector, private sector, or both – and how direct or indirectly it’s provided. The most hands-off way of doing it is through a big fiscal easing at the same time QE is going on. The most direct way is by putting money in the hands of spenders and tying it to spending incentives. Throughout history, governments have applied a variety of approaches.

(For a fuller explanation, please see ‘The 3 Main Forms of Monetary Policy’.)

Because the US is at zero interest rates at the front end of its curve and spreads further out along the curve are at zero, negative, or very close to zero, asset buying is also out of room. So, tertiary monetary policy options have to be its focus.

The European Union is in the same boat as a whole.

China still has room left at the front end of its curve and further out, so it is not as constrained as the others.

The ability to lower interest rates and having more capacity to buy financial assets comes with the benefit of being able to boost asset prices through the present value effect. This is part of the reason why China’s stock market has outperformed others and part of the reason why some investors are more bullish on China’s capital markets than those of developed markets (outside of factors related to China’s higher economic growth and higher risk premiums).

Let’s go through country by country.

United States

We’ll go through monetary and fiscal policy in the US.

Monetary Policy

What we have currently

– Short-term rate cuts of 150bps

– Target fed funds rates of 0.00-0.25 percent

– “Unlimited” QE with purchases of Treasury bonds and government mortgage backed securities. Naturally, the level of collateral that the central bank is willing to buy necessarily reduces the deeper a crisis becomes.

For example, the Fed is now branching into purchasing municipal bonds. The Boston Fed (one of the twelve regional Federal Reserve banks) will lend to eligible banks and financial institutions that can use state and tax-exempt municipal bonds as collateral – assuming the maturities of said debt don’t exceed 12 months. The authorization comes through the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility. It provides an expansion of what had been a program instituted during the financial crisis authorizing the purchase of other assets. The Fed did not purchase assets beyond Treasuries and government-backed mortgage securities during the 2008 crisis.

– Liquidity facilities for households and businesses

Base case scenario

– Front-end interest rates locked at 0.00-0.25 percent

– Purchases of $75bn in Treasuries and $50bn in agency mortgage backed securities ($125bn total) through at least the end of April

– $700bn per month in QE purchases through at least July 1 – i.e., through the end of what St. Louis Fed President James Bullard calls the “national pandemic adjustment period”

– Additional liquidity facilities for continued support to businesses and households

Positive scenario

– Daily $125bn in asset purchases ($75bn Treasuries and $50bn agency MBS) tapered or ended at the end of April (the end of Trump’s currently stated national lockdown period)

– After April 30, $60bn per month in asset purchases at the “before Covid-19” rate, shifted toward the front end of the curve (and not longer duration like traditional QE)

– Asset purchases wound down by 2021

– Resumption of rate hikes 1-2 years in the future

Negative scenario

– Daily $125bn in asset purchases through at least July 1, with $60bn per month after

– Implementation of yield curve control (controlling the front end rate as normal in addition to the 10-year rate at a low but slightly higher rate)

– Additional asset purchases down the quality ladder, such as corporate credit and equity ETFs

– Direct payments to households

– US dollar swap lines expanded beyond Canada, UK, Switzerland, Japan, and EU

Fiscal policy

What we have currently

– Phase One: $8.3bn dedicated toward healthcare spending

– Phase Two: Virus testing, unemployment benefits, paid sick leave

– Phase Three: $2.2 trillion in spending, direct payments (distributed in April), credit guarantees, and tax breaks

– The federal budget will be around minus-20 percent of GDP for the 2020-21 fiscal year

– More fiscal spending will be coming forward, but it will not be on the order of magnitude of the $2.2 trillion bill. Additional rescue packages above $500bn are unlikely unless things worsen or there’s another flare-up of the virus once social distancing restrictions are relaxed.

Positive scenario

– No further fiscal measures needed

– Deficit stays under 20 percent of GDP for the 2020-21 fiscal year

Negative scenario

– Another turn down in the economy (e.g., longer than anticipated “lockdown” and/or additional emergence of the virus later in the year)

– Additional fiscal measures to support the economy

– Monetary and fiscal measures need to move beyond liquidity and credit concerns to supporting solvency

– Fiscal deficit balloons out to 25 percent or more of GDP

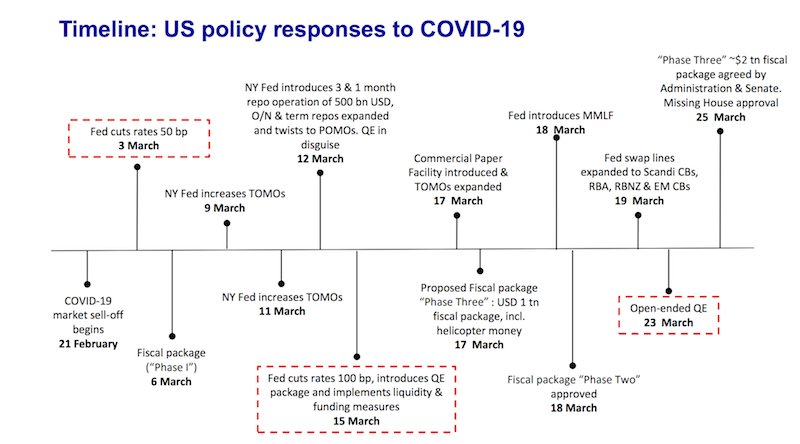

Below a timeline of Fed responses to the coronavirus through March 25:

(Source: Nordea Bank)

Fuller coverage of the US policy response can be found in the Appendix to this article.

European Union

Fiscal and monetary measures taken within the European Union.

Monetary Policy

What we have currently

– Established the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), a temporary asset purchase program worth €750bn to be conducted until the end of 2020

– Regular QE purchases increased by $120bn until the end of 2020

– PEPP will follow the same assets as the standard ECB QE program

– Non-financial commercial paper can be purchased under the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP)

– Additional LTROs will be issued equal to the deposit facility rate (LTROs provide long-term financing for banks to incentivize them to increase lending to businesses and households)

– TLTRO III will be offered at the deposit facility rate minus 25bps

Base case

– No additional rate cuts (rates are already negative)

– PEPP expanded to €1 trillion

– Expansion of issuer limit, or how much of any given country’s bonds the ECB is allowed to buy (at the moment is 33 percent, and could be expanded)

Positive scenario

– No additional ECB measures

– €750bn of PEPP room not needed

Negative scenario

– European Stabilization Mechanism (ESM) and European Investment Bank (EIB) issue “pandemic bonds” (debt tied to catastrophic events to provide funding if natural disasters occur) that the ECB buys

– Additional bond purchases and expansion of PEPP to beyond €1.25 trillion.

– Issuer limits raised to 40 percent or beyond

– Deposit rate cut an additional 10bps or more

– LTROs issued at deposit facility rate minus 50bps

Fiscal Policy

Where we are currently

– EU budget rules have been relaxed

– €37bn in existing EU funds have been used to fight the crisis

– Additional fiscal spending has amounted to around 2 percent of euro area GDP and lending and credit guarantees have come to 13 percent of euro area GDP

Base case

– Emergency packages of each individual country will be taken up by the ECB

– European Stabilization Mechanism will use its existing tools to support credit conditions through the ECCL, expected to be around 2 percent of each country’s output

Positive scenario

– Limited use of the ECCL

– No additional rate cuts

– No extension of individual countries’ fiscal emergency packages.

Downside scenario

– Fiscal stimulus increases to 5 percent of euro area GDP

– ESM or EIB issues pandemic bonds

– Emergency have to be fully taken up by the ECB and extended

– Additional investment programs

China

Monetary Policy

Where we are currently

– Rate cut to 220bps

– Cut to the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) on March 16, 2020

– Loan extensions determined individually for up to one year; any such loan extensions will not be classified as non-performing loans (NPLs)

Base case

– 75-100bps of monetary easing by the end of 2020

– Additional RRR cuts of 150-250bps

– Core CPI inflation is low due to deflationary pressures in the economy from weaker underlying demand (headline demand is high (5 percent) due to shortages of certain food items such as pork)

– New loan approvals, extension of existing loans, and increased issuance of local government bonds; will likely boost credit growth to a 15 percent year-over-year growth rate, up from roughly 10 percent, diverting from the Communist Party’s internal (and necessary) goal to deleverage the economy

Positive case

– No additional rate cuts needed

– Year-over-year credit growth rate remains stable at around 10 percent

– RRR cuts total 100bps in 2020

Negative case

– 150bps or more of rate cuts this year

– 300bps or more RRR cuts this year

– Credit growth increases to more than a 20 percent year-over-year increase

Fiscal Policy

Where we are currently

– Infrastructure projects of CNY6.6 trillion planned, or about 7 percent of GDP

– Businesses are exempt from making employer contributions to pension, unemployment, and work-related injury insurance schemes

– Consumption subsidies, such as travel and auto purchases

Base case

– Corporate tax cuts

– Consumption subsidies

– Infrastructure investment plans up to around 10 percent of GDP, or CNY10 trillion, or about 15 percent y/y growth

– Easing up of housing market restrictions

Positive scenario

– Infrastructure investment growth at 5-10 percent y/y

– Consumption subsidies reduced or repealed

Negative scenario

– Tax cuts more thoroughly needs across the household and corporate level, including consumption (VAT)

– Consumption subsidies expanded

– Housing market restrictions relaxed nation-wide

– Infrastructure plan of 15 percent or more of GDP

Markets’ Digestion of the Policy Response

To this point, we suspect that a lot of the stimulus news across the world’s top three economies has been priced into the markets.

The market may also be underestimating how long the economic shutdown is likely to last and how resilient the virus actually is. President Trump’s goal of opening the economy back up by Easter (around mid-April) was too optimistic and federal restrictions will remain in place until the end of April.

Moreover, similar to past public health pandemics involving highly infectious diseases, there’s always the risk of another wave. The 1918 Spanish flu came in three waves throughout the year. That would be a big shock to world economies and markets given once everything is “back to normal” there will an extrapolation of such going forward.

Capital outflows and commodity shocks have hit emerging markets particularly hard, leading to rebalancing flows that are USD positive. Even despite the Fed’s huge (and necessary) actions in getting money and credit creation going again and a large new wave of dollar supply, the demand for dollars globally is overwhelming. A tighter USD is a headwind against US equities values.

The new money from the stimulus package may take longer than anticipated to get into the economy. A family of four could get up to $3,000 from the new bill. But getting this in the hands of spenders, many of them already strained, could take weeks.

Back in 2009 when a similar approach was used in direct payments to households, it took up to three months to get all the money distributed. Any delay could be a hit to consumption growth and retail sales in the short-run.

Markets dislike uncertainty. Accordingly, a rules-based approach to a relaxation of the lockdowns would be beneficial for risk appetite and cut down on the market’s current level of volatility. Not necessarily a certain date, but the conditions by which an easing of up of restrictions could come to fruition. This would give market participants an idea of what data to look at. Sophisticated investors already do this, but there is not great clarity on how governments are approaching their decision making on the matter.

Appendix

Full US Policy Response Timeline (through March 25)

March 3 (FOMC)

– 50bp cut to 100-125bps

– Treasury bill purchases done through at least Q2 2020

– Overnight repo operations through at least April 2020

March 8 (Congress)

$8.3bn emergency coronavirus response spending package. Included $3 billion in vaccine research. Termed “Phase One”.

March 9 (New York Fed)

Daily overnight repo operations increased from $100bn to $150bn. Two-week repo operations increased from $20bn to $45bn.

March 11 (New York Fed)

Daily overnight repo operations increased another $25bn, from $150bn to $175bn. Two-week repo operations done twice per week. Three one-month term repo operations at $50bn each.

March 12 (New York Fed)

– $60bn in “reserve management purchases”

– Purchases made across a range of maturities to approximately match the maturity composition across all Treasury securities outstanding (nominal bills, notes, bonds, inflation-protected Treasuries (TIPS), and FRN).

– 3-month and 1-month repo operations of $500bn to run on a weekly basis. Integrated with $175bn daily overnight repo operations and $45bn in two-week twice per week.

March 15 (FOMC)

– 100bp cut to 0.00-0.25 percent

– IOER at 0.10 percent

– Forward guidance: Fed asserts its commitment to hold rates near zero “until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.”

– Quantitative easing: Treasury security purchases of at least $500bn and agency MBS of at least $200bn

– Discount window: Encourage depository institutions to use the discount window and allow them to borrow from the discount window for periods as long as 90 days.

– Primary credit rate cut 150bps to 0.25 percent

– Intraday credit: Depository institutions are encouraged to use intraday credit extended by Reserve Banks on both a collateralized and uncollateralized basis

– Central bank swap lines: Re-opened swap lines with five major developed market central banks (ECB, BOJ, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada) to provide liquidity through the standing US dollar liquidity swap line arrangements

– Reserve requirement cut to zero by March 26, or the beginning of the next reserve maintenance period

– Loan guidance: Banks encourages to use capital and liquidity buffers to lend to businesses and households

March 17 (NY Fed)

– Daily overnight repo operations provided twice per day of $500bn each (temporary open market operations, not permanent open market operations)

March 17 (FOMC)

– Established a Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). This facility was authorized under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and by the US Treasury. It will provide $10 billion of credit protection to the Federal Reserve. Pricing is based on the OIS rate plus 200bps.

March 17 (FOMC)

– Established a Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF). This facility will support the credit needs of businesses and households. It will offer overnight and term funding needs with maturities of up to 90 days. It will be in place between March 20 and September 20 and may be extended if conditions warrant it.

March 17 (Congress)

– Democratic leadership in the House of Representatives revise their paid sick leave legislation to two weeks at full pay and ten weeks to two-thirds pay.

– To account for the liquidity crunch many households and businesses have until July 15 (an extra 90 days) to pay their tax bills. This would free up an extra $300 billion in liquidity over this period. Individuals can delay up to $1 million in taxes due and corporations up to $10 million. Tax return forms are still due April 15.

– The Trump Administration proposes to Congress a $1 trillion fiscal package named “phase three”. This would include $250bn in small business loans, $50bn in lending, credit guarantees, and direct payments to the airline industry, and direct payments of $1,200 to all US adults with 2018 or 2019 tax forms on file. The direct payments begins tapering at a gross adjustable income of $75,000 by $5 per every $100 made and down to nothing past $99,000.

March 18 (FOMC)

– Established a Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility. Money market funds are a common savings and investment tool for businesses, households, and a range of larger companies. The MMLF will help money market funds in meeting the demand for redemptions by households and other investors. This will help enhance the overall functioning of the market and the ability to provide credit to the broader economy. The MMLF program is similar to the AMLF program that was launched in the wake of the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008, which caused a major money market fund to fail. This program was approved by the Treasury Secretary and scheduled to run until the end of September.

March 18 (Congress)

– The Senate approved “phase two” of the stimulus package approved on March 13. This includes expanded unemployment benefits, free virus testing, additional Medicaid funding, and required paid sick leave for some workers affected by Covid-19.

March 19 (FOMC)

- USD swap lines expanded to include the central banks of Australia (RBA), Brazil (BCB), Korea (BOK), Mexico, Singapore (MAS), Riksbanken, Nationalbanken, Norges Bank, and RBNZ. The latter three will provided US liquidity of $30 billion each; the remainder will be provided $60 billion each. These arrangements will be in place until at least September.

March 19 (Congress)

A draft bill of “phase three” of the Covid-19 stimulus package was released. The total amounted to $2.2 trillion, or about 10 percent of GDP.

March 20 (FOMC)

To ensure that swap lines are effective in providing US dollar liquidity abroad, the central banks with these swap lines open with the Fed increased the frequency of 7-day maturity operations to daily from weekly. These will last until at least the end of April.

March 20 (FOMC)

Via the MMLF, the Boston Fed will have the authority to make new loans to eligible banks and financial institutions collateralized through assets purchased from state and tax-exempt municipal money market mutual funds.

March 22 (FOMC)

Federal agencies encourage banks and financial institutions to work with borrowers and will not automatically categorize loan modifications as troubled debt restructurings (TDRs).

March 23 (FOMC)

– The Fed announces a form of “unlimited QE” in that it will purchase Treasury securities and agency MBS in the amounts “needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions and the economy”

– The NY Fed’s Trading Desk will by $75bn of Treasury securities and $50bn in agency MBS each business day during the week March 23-27. Agency commercial MBS are also included within the purchases.

– Established the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) for new bond and loan issuance. This helps companies accessing credit the ability to help maintain business operations. It is available to investment grade companies and can help provide short-term “bridge” loan financing of four years. Eligible borrowers can defer interest and principal payments over the first six months of the loan. The Fed is making loans from the PMCCF to companies through a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The Treasury made an equity investment in the SPV through the Exchange Stablization Fund.

– The Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) will help backstop outstanding corporate bonds. This includes individual corporate bonds and US exchange-listed ETFs that provide broad exposure to the market for US investment grade corporate credit. The Fed established an SPV for this facility. The Treasury made an equity investment in the SPV via the Exchange Stabilization Fund.

– The Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) will allow the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS) that are backed by credit card loans, auto loans, student loans, loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA), and certain other forms of loans. The Fed will lend to holders of certain AAA-rated ABS that is backed by recently originated consumer and small business loans. The Fed will lend an amount equal to the ABS’s market value minus a haircut and will be secured by the ABS. The Treasury will also make an equity investment in the SPV used to securitize the TALF through the Exchange Stabilization Fund. The PMCCF, SMCCF, and TALF were all approved by the Treasury Secretary.

– The earlier established MMLF will now include a wider range of collateral, as the economic fallout from Covid-19 is deemed to be worse than anticipated earlier. The MMLF will also include bank certificates of deposit (CDs) and municipal variable rate demand notes.

– The CPFF will also be expanded to include tax-exempt, high credit quality commercial paper as eligible securities. Similar to the MMLF, the CPFF is geared to encouraging the flow of credit to municipalities.

– The Fed also expects to soon establish a “Main Street” Business Lending Program to complement the SBA’s effort to support the flow of credit to small- and medium-size businesses.

March 25 (Congress)

– A “phase three” package of over $2 trillion in credit guarantees, lending support, direct payments and spending, and tax breaks was agreed upon between the Trump Administration and the Senate. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi counter-proposed a $2.5 trillion package, eventually modified to $2.2 trillion.

– Will include $500bn in lending to companies ($50bn to airlines), $350bn to small and medium business, $150bn to hospitals and healthcare businesses, and $250bn in unemployment insurance

– $500bn in direct payments to people. $1,200 per eligible adult and $500 per eligible child.