The Latest on Oil Prices

Coronavirus is the biggest financial (and overall) news story to start the decade.

A distant second, which on its own would be a huge story in more normal times, is the massive hit to oil prices.

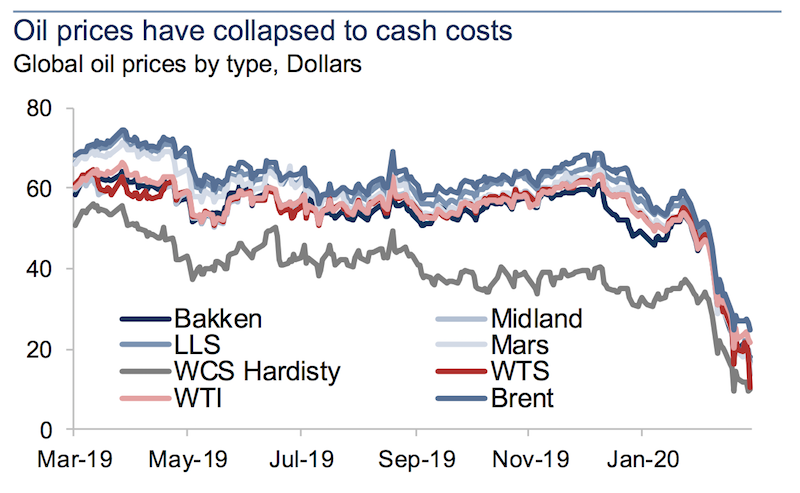

Oil prices have dropped 40 percent since early March after Saudi Arabia and Russia failed to agree on a plan to address an oil market supply glut. Oil inventories continued to build as many of the world’s largest economies went into lockdown to slow the spread of the virus. After an emergency plan failed to materialize, Saudi Arabia cut their prices in an attempt to grab more market share from Russia.

(Source: Reuters, Bloomberg, New York Times, Goldman Sachs GIR)

As a result, this has been the largest oil and commodity price shock since at least the 1930s because it comes at a time where supply was ratcheted up at the same time a large fraction of the global economy was shutting down.

The most analogous period for oil to the current one would be 1998. Oil production was increasing while demand was falling in the wake of the Asian balance of payments crisis and Russian default.

During that period, like what we’re going through currently, the oil industry began to ran out of places to store oil. This had caused WTI oil to collapse further to around $10 per barrel.

Currently, oil supply is increasing as Russia and Saudi Arabia engage in a price battle to control market share.

In Q1, demand went from the expectation of rising by 1 million barrels per day to falling by 6 million barrels per day.

As the US and Europe close down large portion of their economy, even as China comes back, demand is likely to drop by at least 20 million barrels per day, resulting in a historically unprecedented supply glut.

And it’s not just oil itself that’s been impacted. This has implications for the credit market and other financial markets.

Oil exporters have trouble making payments and servicing debt. Many emerging markets borrow in US dollars, the world’s top reserve currency (about 60 percent of global debt is in dollars). The need for dollars relative to their supply presses the dollar higher. This is also a drag on financial asset markets globally as it exacerbates global debt costs.

The prologue to the oil drop

Let’s go through the backstory of what led to the supply issue on the side of “OPEC+”.

In September 2016, OPEC, a select group of oil exporting countries, faced the prospect of lower oil prices without a production cut.

This incentivized the organization to make its first production cut since the steep fall in oil prices during the 2008 financial crisis.

In November 2016, OPEC agreed to trim one million barrels per day from global production. Russia and ten other non-OPEC members also agreed to the cut. This was a bit over 1 percent of global production.

In December 2017, Russia and OPEC to cut production 1.8 million barrels per day until the end of 2018 to take about 2 percent of global supply offline.

In June 2019, Russia and OPEC agree to extend cuts by another six to nine months.

By December 2019, OPEC and Russia agree to further cuts of 2.1 million barrels per day to prevent oversupply in the market, to last throughout Q1 2020.

In March 2020, with oil demand already down to the coronavirus pandemic hitting global prices, Saudi Arabia and Russia decide to stop cooperating on output cuts.

Economically, Saudi Arabia had been taking a disproportionate effect of the output cut. Saudi Arabia also has the advantage of being able to produce at less than $5 per barrel, while Russia’s estimated breakeven cost is around $25-$30.

Pushing more oil into the markets would also place economic pressure on the heavily indebted US shale industry.

So, both Saudi Arabia and Russia ceased cooperating on production restrictions. This extra supply virtually crashed the oil market. At one point, US WTI crude fell to $19 per barrel.

It’s understandable that this agreement between the two countries would eventually fray considering their different needs. It is especially intriguing given it fell apart in the middle of an economic crisis that is worse than the one in 2008 based on the depth of the economic contraction and the breadth of businesses impacted.

Did the coronavirus crash set the stage?

The virus-related demand shock is what put this into motion in the first place. Russia and Saudi Arabia had different views on how to handle it.

The Saudis wanted a big production cut to keep the market in balance. At the same time, they were concerned about what such a cut would do their market share. As mentioned, much of the economic effects of these cuts had fallen on them in the past.

Since 2014, Saudi Arabia has always been concerned about making cuts to the market without getting cooperation from Russia, and wouldn’t follow through without reciprocal action.

The Russians have been more mixed about the benefits of following OPEC and the Saudis on production cuts. They’re considered going their own way in the past.

Moreover, giving up market share is another variable on each side’s mind. Production cuts help boost prices, holding all else equal, directly benefiting US producers.

Since OPEC+ was established, US oil production has increased by over 50 percent. US production in February stood at a record 13.1 million barrels per day. That’s a higher rate than both Russia (11-12 million barrels per day) and Saudi Arabia (9-10 million barrels per day).

Cutting production makes sense in isolation to help improve the economics of oil production and exportation. However, the strategic presence of US shale throws a wrench into the scenario when the US can pump at will.

There’s not a black-and-white solution for either Russia or Saudi Arabia. In the short-term, cuts help. In the long-run, does opening the floodgates and producing more make sense to hit the US shale industry?

The element of sanctions

On top of that, the Russians also have to consider US sanctions on Russian oil assets (Rosneft and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline) into the equation. Sanctions have become a common tool that the US leverages to conduct its foreign policy. US shale oil has helped them exert this power as they are not dependent on foreign oil, on net. The fact that the US imposed sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, an $11 billion project, just as the pipeline neared completion has to be a major source of frustration for the Russians.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has used sanctions to strengthen his relationship with China. Saudi Arabia is a US ally and the relationship has remained intact. But this period could test the cooperation between the two.

Thirteen Republican Senators reach out to Saudi Arabia’s energy minister asserting that the US’s strategic partnership with the kingdom could be damaged if they don’t address the oil market.

President Trump has been notably in favor of lower oil prices. It saves consumers money, gives them more disposable income, and is this is all correlated with the support of political administrations. The 2020 US presidential election has heavily come down to the handling of the virus and restoring economic opportunities.

However, he is concerned about the effect this will have on the economics of US oil production and the damage to the US oil industry. Trump threatened to impose tariffs on crude imports if it means protecting US energy workers from an oil supply glut from producers such as Saudi Arabia.

Low oil prices also create dollar squeezes globally from some countries being unable to meet their obligations (and requiring new borrowing). The increase in the dollar can tighten monetary policy at home and be a drag on the US recovery.

This has pushed his administration and some members of Congress to encourage Saudi Arabia and Russia back to some state of cooperation on restraining production.

Can Russia and Saudi Arabia withstand low prices?

Before the pandemic, Russia was highly favored by emerging market investors with stable fiscal and monetary policy approaches and a solid balance of payments situation. Russia is well-known for its energy-based economy, but it has other resources and projects as well to diversify its economy. For example, the country is the world’s largest wheat exporter. Russia can’t produce oil as cheaply as Saudi Arabia, but it can prove resilient with oil in the $20s for an elongated duration.

Saudi Arabia is working on its own economic diversification efforts, though it will take time.

How long will the oil ‘price war’ last? Who will blink first?

The mean-weighted opinion is that there will be a quick resolution of some sort, or at least a pickup in demand once the pandemic is controlled.

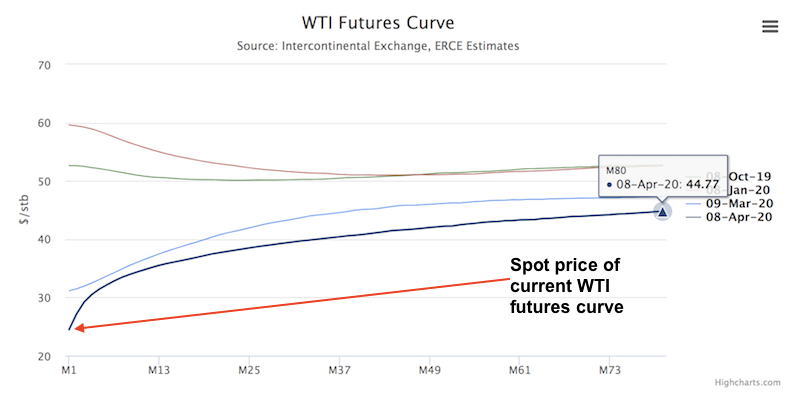

For example, as noted earlier, investors expect oil prices to rise by nearly 60 percent within the next six months looking at the forward futures curve.

Some are more skeptical.

Timelines and decisions on how to handle production can take a long time to come to fruition. From 2014 to 2016, when the market plummeted it took more than two years to agree to production cuts through OPEC+.

But circumstances are different today. The global economy is no longer in good shape. Even if the coronavirus issue is resolved, it will take a while for economies to get back to normal.

Back then, lower oil prices were stimulative to economic growth. Oil going from $100 per barrel to $50 was a big drop when it happened. But it was still low enough to keep production solid while giving a boost to global growth with a lag (outside Russia, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Malaysia, and Norway as the main players) and without inflation.

Today, low prices don’t help stimulate the consumer. People drive less and they fly less while the “stay at home” orders are widely in effect throughout the developed world. The oil recovery will remain invariably tied to the coronavirus related recovery.

As much as the supply issue has gotten attention, the extra supply coming online from Russia and Saudi Arabia is only a small fraction of the demand that was lost.

Political pressure could help at least change the trajectory. Rumors of getting Saudi Arabia and Russia back to the table move prices about 10 percent either way. The 2016 deal was heavily brokered based on a side meeting of Mohammad bin Salman and Putin, so there is already some level of precedent and rapport.

Moreover, Donald Trump is no longer neutral. This year’s Group of 20 (“G20”) meeting is chaired by Saudi Arabia. The purpose of the G20 is to help bring up present issues and improve global economic performance and cooperation. Will the Saudis be willing to change their current perspective on the global oil market?

Can oil go lower?

It can absolutely go lower from the mid-$20s if oil storage capacity is eventually tapped out and oil transportation is severely limited. This was the situation in 1998 when oil dropped to $10 per barrel.

Some traders assume that because a price hasn’t been breached before or in a very long time, that it means it’s unlikely to happen – i.e., a historical price level or whatnot. But that has nothing to do with the cause-effect relationships impacting the present.

Oil going down to the low double digits or even into the single digits is unlikely for now but not out of the realm of possibility. We are not personally betting on that happening (nor are we long oil), as the distribution of potential outcomes is still very high.

Over the long-run – i.e., out 5-10 years – oil should maintain a higher equilibrium price. But that’s already reflected in the futures curve.

The curve is steepest in the very beginning, expecting $30+ per barrel oil within a few months, followed by a long-term equilibrium of about $45.

In the near-term, we’re going to have high inventories simply because of how bleak the demand scenario is. Even if OPEC et al cuts production, there’s simply going to be more supply than demand simply because of how large of a hole has been blown in demand.

The stock market, which is a function of future expected cash flows and interest rates, is most likely to see a V-shaped recovery because of the nature of the equities market and how it prices in the future. And it now has rock-bottom interest rates to increase the present value of those future discounted cash flows and an unprecedented level of liquidity, which is still being dished out.

On the other hand, oil is effectively a supply and demand market. All that inventory is going to be like an anchor on oil prices. It has to be worked off. Thus, the recovery in price is likely to be U-shaped and predicting direction in the short-run is difficult.

Will US shale be permanently harmed?

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the dynamics in the US oil industry were changing.

Before, aggressive growth was the primary goal, believing that cash flow could wait in order to grab more share of the market.

Now, the focus is much more heavily on cash flow and making oil production a profitable business and generating long-term returns.

This means the oil was market was starting to price in less pumping and therefore lower future oil supply coming from US shale.

With the pandemic hurting demand and prices falling, producers are cutting capital spending and bankruptcies and consolidation will need to occur. Either way, it will be a painful period for the US shale industry.

But challenges also breed changes. Operations will reworked. Shale is no longer a new industry and the pandemic has sped along its maturation. These companies will need to become more investor friendly.

Over the past 10-15 years, oil has been a very poor performing segment of the stock market despite the broader market’s huge bull market run from March 2009 to February 2020. The amount of underinvestment in the industry has been large and more investors have focused on ESG initiatives and de-carbonization. This will mean more of a future focus on earnings and being cash flow positive. Committing to dividends is difficult because it essentially means that a portion of your earnings is guaranteed. (Cutting a dividend typically hits the share price hard).

But when the pandemic is over (permanently) and the economy rebounds, what’s the fastest way to get oil capacity back online? It’s through shale.

Its short-cycle nature means that wells can shut in quickly and restart promptly with limited lost capacity. Once demand recovers, the short drilling time and output flexibility is a huge strategic advantage.

Accordingly, the industry still has a large role to play in the global energy markets.

What about the oil majors?

The majors (e.g., ExxonMobil, Chevron), or the large integrated oil companies, will also need to cut back on their spending. They will work to focus on cutting down capital spending on new projects and preserve their dividend.

Oil is a very international industry. If someone gets the virus at a particular drilling site, then that operation may be on hiatus for a while. Travel between countries is down or shut off completely. The whole logistical picture is challenging.

But overall, the oil majors are the best equipped to handle downturns. Their focus on long-cycle assets is generally more stable and accretive to shareholder value. The short-cycle shale-focused companies have tended to destroy shareholder capital and has been a big part of their underperformance.

Will ESG initiatives be harmed because of this?

Some investors integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into their research process. This is another side story to the oil price collapse. More environmentally-friendly technologies are still in their early stages and lack viability in the free market beyond limited use cases.

The cheapness of oil and related products will mean more investment in these products. In that sense, it is realistic to expect that longer-term sustainability and environmental goals could be pushed back to a degree when the free-market economic incentives further favor carbon-based products.

Public companies based on alternative energy products naturally have some sort of “oil price” effect built into their present values. For example, when the price of oil goes down, electric vehicles become less compelling given the cost of operating a gas vehicle falls.

What’s OPEC’s future?

OPEC is now 60 years old. There is clearly much criticism of the organization – “it’s a cartel”, “it colludes, which is/should be illegal”, etc. – and this has gone on for as long as the operation has been around.

However, OPEC’s role in the current storyline in the global oil markets is peripheral. This is really about Saudi Arabia (part of OPEC, but still only ~35 percent of its production), Russia, and the US and that dynamic in the context of the pandemic with an uncertain timeline and a major economic downturn.

Will OPEC rebalance the market?

Clearly, most oil producers – oil exporting countries and oil producing private companies – want higher oil.

The US shale industry, which can turn production on and off much more quickly than longer-cycle projects, has established more control over the oil market globally over the past decade. Part of the calculus behind Russia and Saudi Arabia going their separate ways is a longer-term strategy to push out higher-cost producers. This includes US shale, which has less than stellar economics and often involves lots of borrowing to get projects online.

Many shale producers will need to declare bankruptcy. Many already have or are going to shortly. The US may also deem some of these projects to be strategic assets. The current US administration wants the country to not be dependent on foreign sources of energy, at least on a net basis. Widespread bankruptcies of key oil producers could undermine this objective.

If OPEC were to want to boost prices with cuts, it depends on two things:

(i) When do they cut?

(ii) How much do they cut?

Another important factor lies in the cost of production in the US and among other producers? It’s gone down pretty dramatically since 2014.

The cost of finding and development (F&D) was about $30 per barrel in 2015-16 and was $12 per barrel in 2018-19. If you isolate that variable econometrically, that tends to put WTI crude oil’s fair value in the mid-to-high $40s.

In terms of corporate cost structures, if you’re thinking of putting your money in companies with ~$60 per barrel breakeven prices, that’s probably not a good bet. It’s unlikely that companies, at least those that have a focus on upstream operations, can sustain themselves if they need $60 oil. (The average “oil services” company revenue mix is 60 percent upstream, 25 percent LNG/midstream, 5 percent downstream, and 10 percent other.)

If you want to get into natural gas, you will see a material number of bankruptcies if prices stay sub-1.90/sub-2.00 per MMBTU. It’s not just 2020 prices, but prices in the 2021 curve on out have gone this low as well.

What’s most important in determining the long-term breakeven price of oil?

For many commodities, getting at the key driver that incentivizes production is important. When the sellers and producers in a market can’t sell their goods profitably, it dis-incentivizes production and supply becomes scarcer.

The cost of production is a big one, though different “breakeven points” have different influence.

For example, in the oil market, Saudi Arabia – as covered, a big producer with large influence over the market – the cost of production for a barrel of oil is under $5 (in US WTI terms). But that doesn’t mean it’s the best economic decision to produce as much oil as possible.

Saudi Arabia’s breakeven with respect to its budget (where it has neither a fiscal surplus nor a deficit) is around $70. But that’s also not quite as important because governments can run a deficit.

Saudi Arabia’s balance of payments breakeven WTI oil price is approximately $55. The current account breakeven is the most important of the three because it has the biggest impact on global capital flows.

Oil in the $40s or under for any extended duration requires Saudi Arabia to burn through its foreign currency reserves. It also constricts capital expenditure investments of oil producers. Moreover, if Saudi Arabia and OPEC+ can agree on production cuts to pull oil back up to their balance of payments breakeven, it makes sub-$40 oil unlikely for long periods of time because of how uneconomical it is.

Saudi Arabia is like the Federal Reserve of the oil market as over one third of OPEC’s production. So their motivations matter.

Global demand, once that recovers, will hang around just over 100 million barrels per day, though the growth rate in demand is slowing. Global capacity to produce is higher than that (though official production stats are somewhere around 81mm bpd globally, with about 38% from OPEC), and available supply is somewhat above 100mm bpd.

Price is skewed down due to falling demand/slowing growth and ample production capacity. Higher USD – another knock-on effect of the coronavirus crash (from people owing obligations in dollars and lacking funding) – has had an effect as well.

Securing storage, logistics, and transportation capacity involves needing US dollars. This was a similar concern during the 2008-09 fall in oil.

The Fed offering international swap lines and backstopping various forms of credit helps. Nonetheless, oil, because of its relevance in global trade, creates dollar liquidity on its own. A further drop in oil prices can exacerbate and create additional dollar shortages globally.

Who benefits from low oil prices and who’s disadvantaged?

At the macro level, do the oil consumers (there are more oil consumers than oil producers) increase spending as quickly as oil producers decrease their own spending (through less income and lower investment)? If this is true, the effects globally would theoretically net out.

Oil shocks can have adverse effects both ways. However, oil demand is famously inelastic in the short-run. In other words, over short time horizons, price doesn’t influence demand much.

Lower oil prices are felt more broadly while losses are more concentrated – i.e., among producers and oil exporters. Most economic participants – both individuals, companies, and countries – are buyers or consumers of oil. Few are producers. Holding all else equal, when oil declines, most economies benefit while the losses are concentrated among a few countries.

The US and their oil situation

The US is net flat when it comes to the influence of oil prices on its balance of payments. It exports sweet light crude and imports heavy due to specialized refinery needs. They approximately balance out.

Shale is one of the most elastic (i.e., demand is sensitive to price) parts of the oil supply. Wells get exhausted quickly, so shale producers need to keep drilling to maintain output. If shale aggregate breakeven is about $40 per barrel, then going from $60 to $45 doesn’t mean as much as going from $45 to $30. In the case of the former, a shale producer is still profitable, in the latter production dries up with the economics being destroyed.

Currency effects

Oil exporters with pegged currencies (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Ecuador) are another thing to worry about from the drop. Oil exporters with fixed exchange rates need more FX reserves to keep the peg since they can’t devalue to offset the loss in revenue.

In terms of oil importers, Korea and its currency, in particular, should benefit. They have ample reserves, benefit from the lower price, has fiscal room and a balance of payments surplus, and have also contained the public health matter.

Final Thoughts

Oil is the world’s most important commodity. When the spot price of oil becomes low relative to future months (i.e., the curve is in contango), then the commodity becomes more valuable to store than to use. The futures market expects oil to be $13 higher than it is currently in six months. That’s an expectation of a 57 percent gain.

In normal times, a drop in oil would come to the benefit of most consumers. But because of movement restrictions due to the virus-related lockdown, few are taking advantage.

Moreover, the drop in oil is partially because of weakness in the broader economy. Even in the absence of a Russia-Saudi Arabia price war, oil prices would have gotten crushed. Oil demand at the peak of the coronavirus crash ran at about 80 percent of normal. That means roughly 20 million barrels per day weren’t being consumed.

Is the bottom in on oil?

Due to this blend of circumstances, financially motivated buyers will demand as much physical crude oil as they can store, if they believe they can sell it for a much higher price down the road. Additionally, high-cost producers see the economics of the business become terrible and stop pumping, eventually contributing to a supply shortage. However, there is a long way to go before the supply is inadequate relative to demand.

Oil will not see a V-shaped recovery. It will be U-shaped and carry on over time. It will require a combination of increased demand, which will come from widespread re-openings of the economy and production cuts from OPEC(+) and from the producers taken offline.

Meanwhile, there is limited storage space. Inventories have never been able to take more than 4.7 million barrels per day in any given month historically. Extra storage space will not rise dramatically month to month. From the starting point of the crisis, an extra 20 million barrels of oil were produced in excess of demand.

This means that producers have to fear that the crude they produce may not even be wanted if it can’t be consumed or stored. That makes it likely that crude oil prices will remain lower for longer.

Update

OPEC+, a consortium of the thirteen OPEC member countries plus ten additional countries, agreed to cut 9.7 million barrels from production (per day) on April 12. The organization wanted to reach a deal before markets opened Sunday night to avoid an expected further crash in the market if no agreement came.

Under the final deal, Mexico agreed to cut 100k barrels of daily output. Saudi Arabia initially wanted 350k barrels of cuts from Mexico but met resistance from the country’s president and energy minister.

The US intervened on Mexico’s behalf and agreed to cut some of their own production to help make an agreement given the time constraints they were effectively operating under.

It is believed that the US cut 300k barrels of its own daily production for Mexico alone. Altogether, the US, Canada, and Brazil will restrain up to 3.7 million barrels per day but some of the reductions will be driven by the drop in demand and not based on cooperation with OPEC itself.

While the deal helped avoid a further leg down in oil, WTI prices still remain around $22 per barrel at the time the market opened.