Investing in the Music Industry

The music industry has massive underlying demand and could be of interest for traders or investors looking to get in on a secular trend.

YouTube’s most popular videos and most viewed videos ever are disproportionately music videos. The top ones obtain billions of views, garnering popularity that most forms of content could never fathom even a fraction of from a pure viewership perspective.

At large, the industry is in the most robust competitive position it’s ever been in. Music streaming services have caused the value of the music industry’s assets to skyrocket.

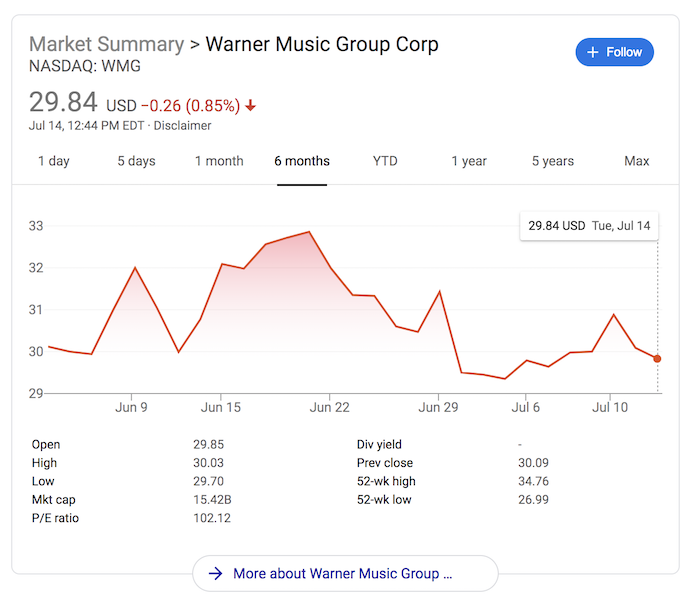

In June 2020, Warner Music went public in one of the largest US IPOs of the year, illustrating the large resurgence in the valuations of music assets. The IPO traded in the upper half of the expected range and has since settled around that debut price.

Warner’s IPO comes on the back of a growing set of valuations in the private merger and acquisition market. Tencent led a consortium of investment in Universal Music. EMI Music Publishing was sold to Sony.

All three of these transactions reflect a level of growth for the owners of music businesses who had owned or purchased these businesses during a time of challenge and transition.

Access Industries purchased Warner Music for $1 billion in equity in 2011.

This was before Sweden-based Spotify, founded in 2008, had launched its streaming service in the US. Today, Warner Music’s market capitalization is more than $15 billion, a 15x money-on-money multiple and a 35 percent annualized return over the holding period.

The Music Industry’s Growth Drivers

The value of the Warner Music IPO followed Spotify’s direct listing two years ago. It gained value in much of the same way – through the collaboration of music artists, content owners, and streaming services brought on by new technological innovations.

This is much different than the music industry of early 2000s. Then, the music industry was seeing declining CD sales and facing challenges from online piracy issues. More companies had to cut costs to remain profitable.

Paid streaming opened a new monetization channel and brought the industry back to better health. Instead of the shrinking industry it was back then, it’s seeing a new wave of growth, with the Warner IPO acting as a testament to its strength.

The Streaming Model and Future Expansion

The streaming model is popular for consumers and has seen widespread adoption in the way people consume music.

It gets delivered to consumers on-demand (similar to video streaming and other content). Digitization allows the data collected on each account to create playlists and personalized recommendations to keep consumers engaged and create value.

These services typically follow a freemium model, where consumers can consume all they want for a limited time period. This also lends itself to high conversion rates for paid subscriptions.

There is also upside for further growth in paid subscriptions, both in developed markets and emerging markets, as music streaming spreads to other parts of the globe along with internet adoption.

Pricing power is also something the industry can play around with. Sweden was an early adopter of the model in the late 2000s with Spotify. They’re currently trying a higher pricing tier. Amazon Music is doing the same with the additional value-add for audio quality.

Close to half (45.4 percent) of Spotify’s 286 million subscribers are Premium subscribers.

The growth in each category is trending proportionally. In year-over-year terms, overall subscribers are up 32 percent (from 217 million) and Premium are up 30 percent (to 130 million from 100 million).

Expansion into Russia, a nascent podcast market, and twelve other Eastern European markets will bring its expansion to 92 countries. Nearly 90 percent of people in Russia stream music online. With a population of nearly 150 million, that makes it the 17th-largest streaming market globally and one that could break the top-10 by 2030.

Wider adoption and potentially higher pricing and/or upsells as time goes on reflect a quality balance of growth tailwinds.

The old model of the music industry

In the decade leading up to 2009 – back when CDs and iPods were the rage – music sales dropped by 56 percent according to the Recording Industry Association of America.

Record labels increasingly looked like they were to become “fax machine” businesses if they didn’t adapt to the digital era. So, some labels like Universal started shifting their business strategies to earn royalties off of streaming services and the burgeoning popularity of social media platforms.

Universal made all the right moves to set the company up for success in the new ecosystem. A brief overview of the sequences of events:

- In 2013, Universal made a deal with Apple to get its artists onto the Apple Music platform. This was two years before the service went live.

- In 2017, Universal negotiated licensing terms with Spotify.

- That same year, it became the first major record label to forge a deal with Facebook. This granted it licenses across Facebook properties, including Instagram, Messenger, and the virtual reality platform Oculus.

- In 2021, it announced a deal with TikTok.

Fast forward to today and Universal makes 70 percent of its revenue from streaming and publishing with continued revenue growth.

Music is in a renaissance period, but the battle over who gets the largest share of the streaming revenue – among record labels, artists, and streaming services – will get increasingly competitive.

Consumer behavior’s influence on the music industry

With the popularity of wireless earbuds and Apple’s AirPods, the consumer is taking in more audio content than ever.

The adoption of smart devices and speakers in homes like Alexa and Google Assistant, which often are used to play music, has also paved the way for more music consumption, as well as greater varieties of it.

For instance, parents who set up a smart speaker in a child’s room are more likely to stream child-focused songs. This helps the popularity of new catalogs of music.

Moreover, an increasing number of services, like Peloton (exercise equipment), license and incorporate music playlists into their products. This helps deepen overall consumer interaction with music and helps diversify and broaden the industry’s revenue base.

The diversification value of music

There is a lot of value in adding something uncorrelated to your portfolio in the way it improves your reward relative to your risk.

At the same time, songs of well-known performers (e.g., Michael Jackson, Paul McCartney) are very expensive. As a result, more investors are looking for different genres like jazz or newer performers that may be more of a “value play” now but increase in price as their career resume stacks up.

Song catalogs can be good investments because of the royalty payments they generate. They’re sometimes compared to bond-like investments in that they have the capacity to throw off steady and relatively passive income.

However, with music catalogs, the income they generate can be volatile.

There’s a large skew in the distribution of income generated. Royalty payments are high soon after a track is released and then decay fairly rapidly.

After a few years, the income a song generated could be up to 90 percent below what it was making at its peak.

So there’s always the danger of paying too much for music by extrapolating recent earnings that are likely to decay quickly.

Investments in artists’ catalogs that are still widely being listened to decades from now could pan out greatly.

But they also carry risk in the event royalties decay down to a very thin tail. In that event, can enough income be pulled out of the investment over its life to get back your initial investment plus a respectable return?

Investors who are more risk-averse but still want exposure to music can stick with more timeless artists who have proven themselves over decades and retain large fanbases.

Music’s rise as an alternative asset class

Money poured into music catalogs in the early 2020s.

Major record labels, private equity firms, and specialist funds such as Hipgnosis spent a total of more than $12 billion on the rights to songs by artists such as Tina Turner and The Beach Boys, based on data from MIDiA Research. The money that went into music rights was more than double the previous record set in 2020.

Demand for music publishing rights grew as low interest rates pushed yield-seeking investors into alternative assets. Song catalogs are sometimes compared to high-yield bonds for the steady income they pay out in the form of music royalties.

Higher interest rates, however, could dent demand for music catalogs if investors are able to find attractive yields elsewhere, or switch to assets that could keep better pace with inflation, such as certain types of real estate.

Inflation, especially if it runs hot, will reduce the purchasing power of future cash flows generated by music catalogs.

Mechanical royalty rates set among US policymakers haven’t historically kept pace with changes in consumer prices for goods and services.

How do musician’s make money through music?

Musicians can monetize their talent and work through various streams of income.

Here’s a detailed list of how they can make money from their music:

1. Record Sales

- Physical Sales – Selling physical formats like CDs, vinyl records, and cassettes.

- Digital Sales – Selling digital downloads of songs or albums through platforms like iTunes or Amazon Music.

2. Streaming Revenue

- Streaming Platforms – Earnings from platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube through play counts and ad revenue sharing.

3. Live Performances

- Concerts and Tours – Ticket sales from live performances, including both solo shows and tours.

- Private Gigs – Performing at private events, parties, or corporate functions.

4. Merchandising

- Apparel and Accessories – Selling branded merchandise like T-shirts, hats, and posters.

- Special Items – Limited edition items or memorabilia, including signed instruments or special edition vinyl.

5. Licensing Fees

- Sync Licensing – Earning fees from having music used in movies, TV shows, commercials, video games, or other media.

- Mechanical Royalties – Royalties from the reproduction of songs (e.g., when music is covered by other artists).

6. Publishing Royalties

- Performance Royalties – Royalties collected when a song is played on radio, television, or live venues.

- Digital Royalties – Royalties from the use of music on digital platforms, including streaming, downloads, and ringtone purchases.

7. Royalties from Songwriting and Composition

- Songwriting Credits – Earnings from writing music or lyrics, which are paid through royalties every time the song is played or covered.

8. YouTube Monetization

- Ad Revenue – Earnings from ads played on their own music videos or user-generated content featuring their music.

- Channel Subscriptions – Revenue from subscribers paying for premium content on the artist’s YouTube channel.

9. Fan Funding and Crowdfunding

- Patreon and Similar Platforms – Regular income from fans who subscribe to receive exclusive content or experiences.

- Kickstarter Campaigns – Funds raised for specific projects like new albums or tours, often with tiered rewards for backers.

10. Teaching and Workshops

- Music Lessons – Income from teaching instruments or vocal lessons.

- Workshops and Master Classes – Hosting sessions on songwriting, music production, or industry-specific skills.

11. Session Work and Collaborations

- Studio Sessions – Being hired as a session musician to play on other artists’ recordings.

- Collaborative Projects – Partnering with other artists or brands, which can also lead to shared revenues from any resulting music.

12. Music Production

- Producing for Others – Earning fees for producing tracks or albums for other artists.

- Mixing and Mastering Services – Offering technical services for refining the sound quality of recordings.

13. Music Writing and Journalism

- Articles and Blogs – Writing about music or musicians for publications or independent blogging.

- Book Sales – Writing and selling books related to music instruction, music theory, or music industry insights.

14. Grants and Sponsorships

- Music Grants – Funds provided by governmental bodies or private organizations to support music projects.

- Brand Sponsorships – Financial support from brands for tours, music videos, or endorsements.

15. Residencies

- Regular Performances – Paid engagements where the musician performs regularly at a particular venue over a set period.

Each of these revenue streams requires different skills and approaches, and the success in each can vary widely depending on the artist’s popularity, network, and industry changes.

Nonetheless, diversifying income sources can help musicians achieve a more stable and sustainable career in the music industry.

How do record labels make money?

Record labels make money via:

- Record Sales – Selling physical formats like CDs and vinyl, and digital downloads.

- Streaming Revenue – Earnings from platforms like Spotify and Apple Music.

- Live Performances – Ticket sales for concerts and tours.

- Merchandising – Selling branded merchandise.

- Licensing Fees – Fees from music used in media such as films and commercials.

- Publishing Royalties – Royalties from radio plays and digital use.

- YouTube Monetization – Ad revenue and subscriptions from YouTube.

Conclusion

For all its ups and downs and unique challenges, the music industry is largely in better shape than it ever has been.

Affordable “all-you-can-consume” streaming services have helped provide a consumer-friendly way of getting the music they want on-demand. With the help of data and algorithms, music platforms can help consumers with better personalization in their feeds and recommendations and keep them engaged with the service longer.

People are consuming music more and in different ways through new services and through the proliferation of various audio devices in their daily lives.

The combination of these forces has led to robust growth tailwinds in the music industry that are likely to continue.