How Interest Rates Impact Banks

Interest rates play an important role in how a bank makes money.

Interest rates influence a bank’s business both directly – i.e., driving loan, securities and deposit pricing and borrowing costs – and indirectly – i.e., impacting loan demand, default rates, and capital markets activity.

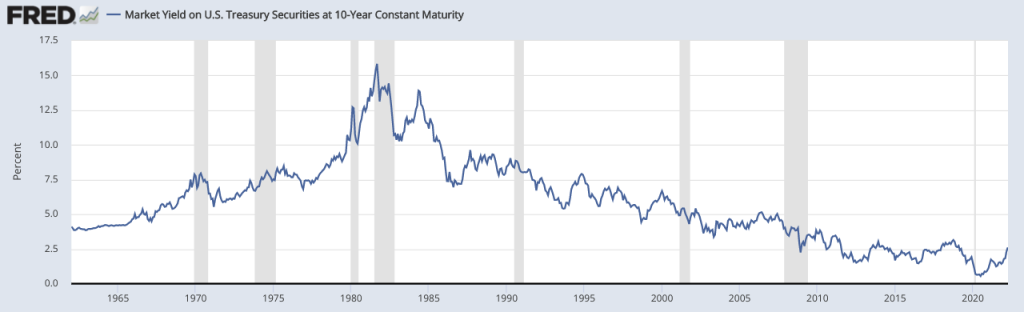

Over the past more than four decades, interest rates have been in a steady decline since peaking in 1981, with the 10-year Treasury mostly hanging in the 0 to 3 percent range since the 2008 financial crisis vs. being 14 percent in 1981.

Market Yield on US Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity

(Source: Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

As a result, banks have typically gone the route of maintaining liability-sensitive balance sheets over this period, taking advantage of faster declining funding costs (liabilities) versus slower-declining investment yields in loans/securities (assets).

When the yield curve is at steep levels – the 10-year vs. 3-month Treasury spread has been about 1.35 to 1.40 percent over the past 50 years – banks will play the carry trade.

This means funding higher-yielding fixed assets like securities with shorter-term, lower-cost liabilities.

The concern is what happens if rates were to rise sharply or the yield curve was to flatten and banks were caught in a meaningful asset-liability mismatch (as what happened during the S&L crisis during the late-80s into the early-90s).

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at this and the various other impacts interest rates and the yield curve have on the banking industry.

Interest Rates – Impact on Bank Loans

Interest rates notably impact the cost of business loans.

Interest rates are a key driver of loan yields

The interest rates on both new and existing loans will usually increase when the Federal Reserve (Fed) raises interest rates.

Banks tend to raise the interest rates they charge customers more quickly than the interest rates they pay to depositors.

Loan demand also slows as businesses and consumers alike slow down their borrowing in response to higher interest rates.

In particular, businesses are often reluctant to take out loans for big-ticket items such as equipment or expansion when interest rates are high.

This can lead to a decline in business lending, which can hurt banks’ profits.

Declining interest rates are generally a positive for loan growth

Businesses and consumers are more likely to take out loans when interest rates are low.

But there is a limit to how much lower interest rates can go before they turn negative, at which point they start discouraging borrowing instead of encouraging it.

This is why we’ve seen interest rates falling around the world in recent years, with some countries even experimenting with negative interest rates.

Interest rates can go a little bit below zero, but not too much below.

Central banks always want to avoid deflation, so at a point, negative interest rates guarantee that a creditor will be losing money in both nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

Declining long-term rates help mortgage purchase activity, but other factors at play

Falling interest rates can lead to an increase in mortgage purchase activity as more people refinance their mortgages and home buyers are able to get lower interest rates on new loans.

But other factors, such as job security and wage growth, also play a role in determining whether or not someone will buy a home.

For example, even if interest rates are low, people may not want to take on the responsibility of a mortgage if they’re worried about losing their job. Low interest rates naturally tend to signal economic weakness.

Sharp declines in interest rates spur mortgage refinancing activity and help banks’ mortgage businesses

When interest rates decline sharply, as they did during the Great Recession, it can lead to a surge in mortgage refinancing activity.

This is because people who have adjustable-rate mortgages or loans with high interest rates may want to refinance into a new loan with a lower interest rate.

Banks typically make money on mortgage refinancing by charging origination fees and collecting interest on the new loan over time.

Interest Rates – Impact on Deposits

Interest rates play an important role in liability management.

Interest rates also have a big impact on banks’ deposit business.

When interest rates rise, depositors will often withdraw their money from banks in search of better returns elsewhere.

To prevent this from happening, banks will usually raise the interest rates they pay on deposits to keep pace with rising interest rates.

This can put pressure on banks’ interest margins, which is the difference between the interest rates they pay on deposits and the interest rates they charge on loans.

Rising interest rates can also lead to increased costs for banks, as they may have to offer higher interest rates on certificates of deposit (CDs) and other products to compete with other banks.

When interest rates fall, people are less likely to move their money around in search of better returns.

This can help banks’ deposit businesses, as people are more likely to keep their money in an account that earns some interest than one that pays no interest at all.

But falling interest rates can also lead to lower interest income for banks, as the interest rates they earn on loans will often fall as well.

This can put pressure on banks’ interest margins and bottom lines.

That’s why interest rate movements are so important for banks. They can have a big impact on banks’ profits, as well as the overall economy.

Deposit repricing typically lags changes in interest rates by six to nine months

The interest rates banks charge on loans often change more quickly than the interest rates they pay on deposits.

This is because banks can’t immediately change the interest rates they pay on deposits without losing customers to other banks.

Instead, banks will typically wait six to nine months before changing the interest rates they pay on deposits.

This lag gives banks time to adjust their interest margins and bottom lines to account for changes in interest rates.

Interest Rates – Impact on Net Interest Margin (NIM)

Net interest margin (NIM) is the difference between the interest income a bank earns on its loans and the interest expense it pays on its deposits.

Changes in interest rates can have a big impact on NIM.

When interest rates rise, NIM typically expands as interest income increases more than interest expense (i.e., loan income growing faster than deposit payouts).

But when interest rates fall, NIM usually contracts as interest expense decreases more than interest income (i.e., loan income falls faster than deposit savings).

This is why changes in interest rates can have a big impact on banks’ profits.

Rising interest rates are good for banks because they often lead to an expansion in NIM. But falling interest rates can be bad for banks because they can cause a contraction in NIM.

Interest rate movements are therefore an important factor to consider when investing in banks.

Interest Rates – Impact on Securities Portfolios

Banks hold securities, such as bonds, in their portfolios.

The interest rates on these securities can change over time.

When interest rates rise, the value of these securities often falls.

This is because of the present value effect and the interest rates on new securities are usually higher than the interest rates on existing securities.

As a result, banks may have to mark down the value of their securities portfolios when interest rates rise.

This can have a negative impact on banks’ profits and capital levels.

On the other hand, when interest rates fall, the value of these securities usually rises.

So, the interest rates on new securities are usually lower than the interest rates on existing securities.

As a result, banks may have to mark up the value of their securities portfolios when interest rates fall.

This can have a positive impact on banks’ profits and capital levels.

Changes in interest rates can therefore have a big impact on banks’ profits and capital levels.

Investors should therefore be aware of how changes in interest rates can affect banks’ financial condition before making investment decisions about banks.

Rising interest rates could lead to securities losses for banks

If interest rates rise faster than expected, banks may have to mark down the value of their securities portfolios.

This could lead to securities losses for banks.

And these losses could reduce banks’ profits and capital levels.

Falling interest rates could lead to write-downs of loans and other assets

If interest rates fall, the value of some of banks’ loans and other assets may decline.

As a result, banks may have to mark down the value of their loans and other assets when interest rates fall.

Prolonged low interest rates may lead to reinvestment risk for banks

If interest rates remain low for a long time, banks may have to reinvest their interest income at lower interest rates.

This could lead to reinvestment risk for banks.

And this risk could reduce banks’ profits and capital levels.

Interest Rates – Impact on Credit Costs

Credit costs are interest expenses incurred on loans and other borrowing, which reduces interest income earned on these assets.

When interest rates rise, credit costs usually increase.

For example, if a bank has more exposure to variable rate loans, a rise in rates would lead to larger payments for borrowers. This is especially true if they are longer term loans like auto or home.

This would create a larger cash flow burden and therefore likely more defaults.

If a bank has more exposure to fixed rate loans, a drop in rates may increase defaults, since borrowers who are not able to refinance would rather not make payments when lower rates are available (and therefore go into default).

And even if the borrowers were able to refinance (which would lower default rates), a bank would not be able to benefit from being in fixed rate loans because its loan book would refinance to variable rate and therefore become more rate sensitive.

Bank Interest Rate Sensitivity

A bank’s sensitivity to interest rates is determined by how quickly its assets (i.e., loans and securities) change in price relative to its liabilities (i.e., deposits and borrowings) given a change in interest rates.

Banks historically have been liability sensitive – meaning their liabilities reprice faster than their assets – given the yield curve is typically positively sloped and the multi-decade secular decline in interest rates.

A prolonged low interest rate environment generally hurts banks if they are asset sensitive.

But assuming interest rates eventually need to rise off current record low levels, banks that are more asset sensitive (i.e., the banks that, on average, see their assets reprice faster than liabilities) will be positioned better to deal with this.

Limitations of bank disclosures on interest rate sensitivity

Although banks are required to disclose certain information about their interest rate sensitivity, such disclosures have limitations.

First, interest rate sensitivity disclosures are often presented in a hypothetical way that may not reflect actual changes in interest rates.

Second, interest rate sensitivity disclosures often exclude the impact of derivatives and other financial instruments that can be used to hedge interest rate risk.

Why banks haven’t been positioned for rising rates until more recently

One reason banks haven’t been positioned for rising interest rates until more recently is that interest rates have been at historically low levels for a long time.

Due to a confluence of factors, such as lots of debt relative to output, aging demographics, and globalization, inflation had remained muted, leading to lower inflation rates.

It’s natural to extrapolate the past when the environment we’ve been in has been that way for decades.

Now that the Federal Reserve is taking inflation more seriously, and is expected to continue doing so, banks are starting to position themselves for higher interest rates.

This is why you may see some banks raise their prime lending rate or increase the interest rates on their certificates of deposit.

Why do traders, banks, and other market participants care about the yield curve?

Investors keep a close watch on the US yield curve — the gap between short-term and long-term Treasury rates — for signs that economic growth could reverse.

When that measure does invert it typically means short-term Treasuries yielded more than the ones that mature in a decade.

10-year Treasuries are considered the safest, most liquid investments available, and their yields tend to drop below short-term rates when market participants are concerned about economic growth.

Does the yield curve have predictive ability?

The yield curve’s predictive ability may have been clouded by the spike in inflation.

When inflation jumps, it’s more common for the yield curve to flatten or even invert.

Furthermore, researchers at Goldman Sachs have found that the curve using inflation-adjusted yields (real rates) is still positive and hasn’t inverted.

Doing the same analysis based on data from periods of higher inflation (from 1971 to 1991), strategists at Goldman Sachs found a slightly lower chance of recession.

Real and breakeven rates had a stronger statistical significance for forecasting an economic downturn using data from that time period.

Yield Curve – Impact on the Carry Trade

The yield curve is important for banks because it affects their profitability and interest rate risk.

The yield curve is a graph that shows the relationship between interest rates and the maturity of bonds.

Typically, bonds with longer maturities have higher interest rates than bonds with shorter maturities.

This is because investors require a higher return to compensate them for the risk of holding a bond for a longer period of time.

The yield curve can be upward-sloping, downward-sloping, or flat.

- An upward-sloping yield curve is often referred to as a “normal” yield curve.

- A downward-sloping yield curve is often referred to as an “inverted” yield curve.

- A flat yield curve is often referred to as a “neutral” yield curve.

The shape of the yield curve can have a big impact on banks’ profitability and interest rate risk.

When the yield curve is upward-sloping, banks can profit from the “carry trade.”

The carry trade is when banks borrow money at a low interest rate and use the money to buy securities that pay a higher interest rate.

Example of a bank carry trade

For example, if the interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills is 2 percent, and the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is 3 percent, a bank could borrow, e.g., $100 million at 2 percent and use the money to buy 10-year Treasury bonds.

The bank would then earn interest on the 10-year Treasury bonds while only paying interest on the 3-month loan.

This would be a profitable trade for the bank as long as interest rates stay relatively stable.

However, if interest rates rise, the value of the 10-year Treasury bonds would fall, and the bank could lose money on the trade.

When the yield curve is downward-sloping or flat, it can be difficult for banks to profit from the carry trade.

This is because banks would be borrowing at a higher interest rate than they could earn by investing in securities.

As a result, banks may avoid the carry trade when the yield curve is downward-sloping or flat.

The shape of the yield curve can also have an impact on banks’ interest rate risk.

When the yield curve is upward-sloping, banks typically have more interest rate risk because they are more likely to experience interest rate increases.

The carry trade helped set off the Savings and Loans crisis in the early 80s

In the early 1980s, interest rates in the United States rose sharply as a way to end the inflation problem that had started more than a decade ago.

This caused the value of many bonds to fall, and banks that had invested in bonds through the carry trade lost a lot of money.

The losses suffered by banks helped set off the Savings and Loans crisis.

Interest rate risk is also a big concern for banks when the yield curve is flat or inverted.

An inverted yield curve occurs when interest rates on short-term bonds are higher than interest rates on long-term bonds.

A flat yield curve occurs when interest rates on short-term bonds and long-term bonds are about the same.

Both an inverted yield curve and a flat yield curve can signal that a recession is coming.

This is because an inverted yield curve often occurs when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates to slow down the economy and prevent inflation.

A flat yield curve can also signal that the economy is slowing down.

When the yield curve is inverted or flat, banks may be less likely to lend money because they are worried about getting repaid.

A slowdown in credit creation is commonly what causes a recession.

Carry trade strategies based on the yield curve can be risky

The yield curve can be a helpful tool for understanding interest rates and how they may impact banks.

However, it is important to remember that carry trade strategies based on the yield curve can be risky.

Banks can lose a lot of money if interest rates rise or if the yield curve inverts.

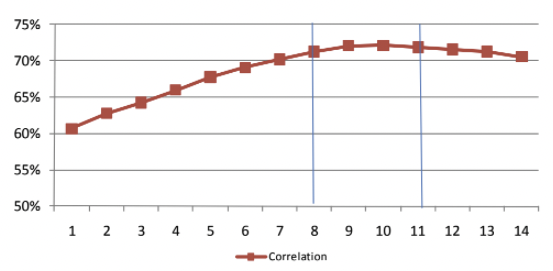

Securities repositioning generally lags interest rate changes by eight to ten months

The interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond is often used as a benchmark for setting interest rates on mortgages, auto loans, and other types of loans.

This is because the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond is a good indicator of where interest rates are headed in the future.

However, it is important to remember that securities repositioning generally lags interest rate changes by eight to ten months.

This means that interest rates on loans may not increase immediately after the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond increases.

Banks use a variety of factors to set interest rates on loans, and the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond is just one of these factors.

Correlation of securities/earning assets vs. yield spread

(Source: Deutsche Bank)

A flatter or even inverted yield curve still makes the carry trade possible

Banks may decide to invest in riskier securities.

If cash rates go up to match longer-duration bond yields, they can still borrow cash and invest in things like corporate credit, stocks, private assets, and other things that are likely to give them higher yields than longer-term bonds.

Basically anything involved in borrowing a lower-yielding asset to invest in a higher-yielding asset is a carry trade.

Yield Curve – Impact on Earnings and Value of the Firm

The interest rate environment has a significant impact on banks and other financial institutions.

In general, a steeper yield curve is more favorable for banks because it allows them to earn a higher spread between the interest rates they charge on loans and the interest rates they pay on deposits.

A flatter or even inverted yield curve still makes the carry trade possible, just as long as higher-yielding assets are still available, no matter where they come from.

When interest rates are low, it becomes more difficult for banks to earn a profit.

Banks may respond to this by reducing lending, which can have a negative impact on economic growth.

Flattening/inverted yield curve generally pressures earnings and book value

In addition, a flattening or inverted yield curve generally pressures earnings and book value.

This is because the interest rate on loans is usually higher than the interest rate on deposits.

If the interest rate on loans decreases while the interest rate on deposits remains the same, then the spread between these two rates will narrow.

This can reduce the amount of net interest income that banks earn – about 65 percent of their overall revenue – and put downward pressure on their stock prices.

A steepening yield curve is often better for earnings and book value

A steepening yield curve, on the other hand, is often better for earnings and book value.

This is because a steepening yield curve usually means that interest rates are increasing at longer-duration bond maturities.

If the interest rate on loans increases faster than the interest rate on deposits, then the spread between these two rates will widen.

This can increase the amount of net interest income that banks earn and put upward pressure on their stock prices.

An inverted yield curve often signals weakness in the economy

It is important to remember, however, that an inverted yield curve often signals weakness in the economy.

An inverted yield curve occurs when interest rates on short-term loans are higher than interest rates on long-term loans.

This can happen when investors are worried about the future and believe that interest rates will fall.

If interest rates do fall, then banks will be forced to lower the interest rates they charge on loans.

This can reduce the amount of net interest income that banks earn and put downward pressure on their stock prices.

Yield Curve – Impact on the Balance Sheet

The interest rate environment also has a significant impact on the balance sheet of banks and other financial institutions.

A flatter yield curve generally means that the value of assets on the balance sheet will decline.

If interest rates fall, then the interest that will be provided by bonds and other interest-bearing assets will decline.

At the same time, the value of loans will also decline because lower interest rates make loans less valuable.

A steeper yield curve, on the other hand, often results in an increase in the value of assets on the balance sheet.

Banks generally restructure securities books as the yield curve flattens

In addition, banks generally restructure their securities books as the yield curve flattens out.

They do this by selling off securities with longer maturities and reinvesting the proceeds in securities with shorter maturities.

This helps to protect the value of the securities book and reduces interest rate risk.

It also helps to ensure that the bank has enough liquidity to meet customer demands.

Mortgages tend to remain stable regardless of the yield curve

The interest rate environment has a significant impact on the balance sheet of banks and other financial institutions. But mortgages tend to have less volatility despite the relative steepness of the yield curve.

This is largely because mortgage interest rates are generally fixed for the life of the loan.

Even if interest rates rise, most homeowners will not see their monthly payments go up.

And if interest rates fall, homeowners may be able to refinance their loans and get a lower interest rate.

This stability makes homes, and the mortgages that come with them, an attractive investment for many people, even when interest rates are low.

Deposit costs rise as the yield curve flattens

The interest rate environment also has an impact on the cost of deposits.

A flatter yield curve occurs when either:

- short-term rates rise (which is typically the case) or

- when long-term rates fall

If short-term interest rates rise, banks need to increase the return on customer deposits to correspond with these higher market rates.

If the yield curve flattens because rates fall on the long end, yields on longer-dated investments may not be as attractive to a bank. Therefore, it must lower deposit costs to maintain the spreads it receives.

Changes in deposit pricing tend to lag changes in the yield spread by six to nine months (with a negative correlation of 90-95 percent).

Yield Curve – Impact on Net Interest Margin (NIM)

The interest rate environment has a significant impact on the net interest margin (NIM) of banks.

NIM is the difference between the interest income earned on loans and the interest expense paid on deposits.

A flatter yield curve generally results in a lower NIM because the interest rate differential between loans and deposits is smaller.

This can put downward pressure on bank stock prices.

A steeper yield curve, on the other hand, often results in a higher NIM because the interest rate differential between loans and deposits is larger.

This can lead to an increase in bank stock prices.

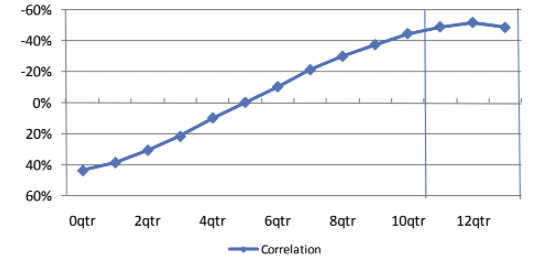

Yield Curve – Impact on Credit Costs

The interest rate environment also has a significant impact on credit costs.

As the yield curve flattens, credit costs generally rise.

This is because the interest rate on loans is often higher than the interest rate on deposits.

The result is that the spread between the interest rates on loans and deposits narrows.

This can put upward pressure on borrowing costs and lead to an increase in non-performing loans.

A steeper yield curve, on the other hand, often results in lower credit costs.

This is because the interest rate on loans is often lower than the interest rate on deposits.

The result is that the spread between the interest rates on loans and deposits is wider.

This can lead to a decrease in borrowing costs and non-performing loans.

Moreover, a flattening yield curve usually suggests that the economy is getting weaker, which leads to deteriorating credit quality, leading to more net charge-offs (NCOs).

Correlation of bank NCOs and yield spread

(Source: Deutsche Bank)

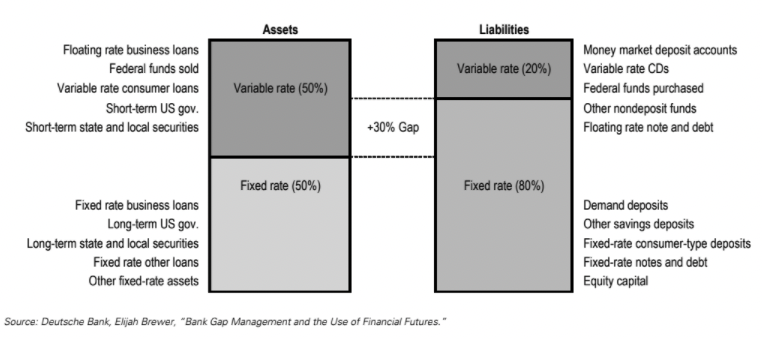

Asset-Liability Management

For banks, asset-liability management (ALM) is the process of managing the interest rate risk of the bank’s balance sheet.

The goal of ALM is to maximize the interest rate spread between the interest income earned on loans and the interest expense paid on deposits while minimizing the interest rate risk.

ALM is a dynamic process that requires banks to constantly adjust their portfolios in response to changes in interest rates.

Example of positive duration gap (asset sensitive bank)

(Source: Deutsche Bank)

The pitfalls of aggressive gap management

Aggressive gap management could be bad for shareholder wealth despite increasing net interest income in the short term due to interest rate risk, especially on the asset side.

In the specific case of the carry trade, longer-duration assets would decline more in dollar value than shorter duration assets if interest rates were to rise (higher duration = more interest rate sensitive) and these assets were sold (likely leading to large losses).

Money market instruments are useful for adjusting a bank’s interest rate sensitivity

An interest rate swap is an example of a derivative instrument that can be used to manage interest rate risk.

In an interest rate swap, two parties agree to exchange cash flows based on different interest rates.

For example, one party may receive a fixed interest rate while the other party pays a variable interest rate.

Interest rate swaps can be used to adjust the interest rate sensitivity of a bank’s balance sheet.

They can also be used to hedge against changes in interest rates.

Banks use derivatives to manage their interest rate risk

Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from the underlying asset.

Examples of derivatives include futures contracts, options, and interest rate swaps.

Derivatives can be used to manage the interest rate risk of a bank’s balance sheet.

They can also be used to hedge against changes in interest rates.

Overall, derivatives as an interest rate management tool provide flexibility and allow banks to tailor their portfolios to their specific needs.

Managing Interest Rate Risk

Generally, there are two different approaches that banks will use to manage interest rate risk:

1) On-balance sheet strategies (i.e., loans, deposits, and securities), and

2) Off-balance sheet strategies (i.e., interest rate swaps, futures, forward contracts)

On-balance sheet interest rate risk management

On-balance sheet interest rate risk management involves managing the interest rate risk of the assets and liabilities on a bank’s balance sheet.

This can be done by actively managing the mix of interest-bearing assets and liabilities, as well as the repricing terms of these items.

For example, a bank may choose to invest in shorter-term securities in order to minimize interest rate risk.

This also makes more sense when the yield curve is flatter or inverted because shorter-term securities will yield about the same but with less interest rate sensitivity.

Or, a bank may choose to offer loans with variable interest rates in order to take advantage of higher interest rates.

Off-balance sheet interest rate risk management

Off-balance sheet interest rate risk management involves using derivatives to manage the interest rate risk of a bank’s balance sheet.

Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from the underlying asset.

Examples of derivatives include interest rate swaps, futures contracts, and options.

Banks can use derivatives to design very specific exposures, especially in ways that can limit their risk.

For example, a bank may use interest rate swaps to hedge against changes in interest rates.

Or, a bank may use interest rate futures to speculate on future changes in interest rates.

Conclusion

Interest rates are a material part of a bank’s financial performance in various ways.

This includes impacts on assets and liabilities, the interest they charge on loans and pay out on deposits, the types of securities trading they do, net interest margins (NIMs), asset-liability management (ALM), and more.

Banks use various interest rate risk management techniques, both on and off-balance sheet, in order to manage their interest rate risk.

These techniques include actively managing the mix of interest-bearing assets and liabilities, as well as using derivatives to hedge against or speculate on future changes in interest rates.