Curve Steepener Strategies

A curve steepener is used to express the view that the spread between long-term and short-term rates will widen. (As opposed to a curve flattener, which is a view that the spread between long-term and short-term rates will compress.)

That widening can occur because:

- a) long rates rise faster than short rates, or

- b) because short rates fall faster than long rates

The why matters as much as the how. Different steepeners thrive in different macro regimes.

We’ll look through them and cover the nuances of the steepener trade.

Key Takeaways – Curve Steepener Strategies

- A curve steepener is a way to bet on the view that the gap between long-term and short-term rates will widen.

- Steepening can happen two ways:

- long rates rise faster, or

- short rates fall faster

- The macro regime matters more than the trade structure.

- Reflationary (bear) steepeners work when growth and inflation expectations rise faster than discounted.

- Policy-pivot (bull) steepeners work when growth breaks and central banks cut rates aggressively.

- Fiscal-dominance steepeners have to do with debt stress and rising term premia, not strong growth.

- Curve steepeners are fundamentally regime signals.

- Get the macro right first, then choose the cleanest expression.

- Considering the carrying costs of curve steepeners.

- If you are long a steepener in an upward-sloped curve, it has negative carry. (Long a steepener in an inverted yield curve produces positive carry.)

1) Reflationary (Bear) Steepeners

Mechanism

Long rates up, short rates anchored

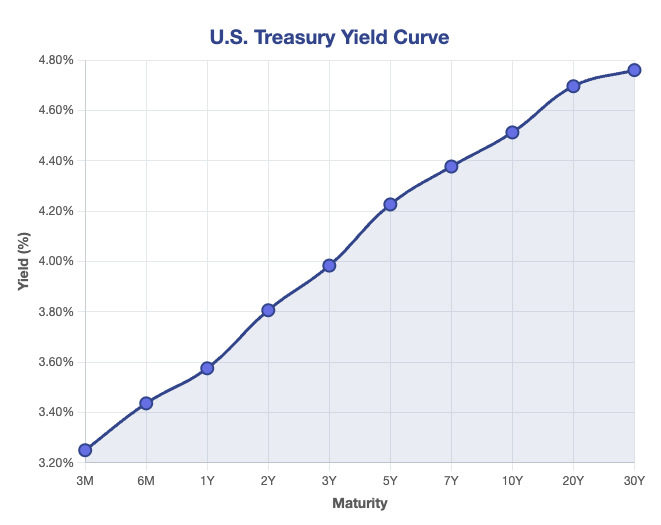

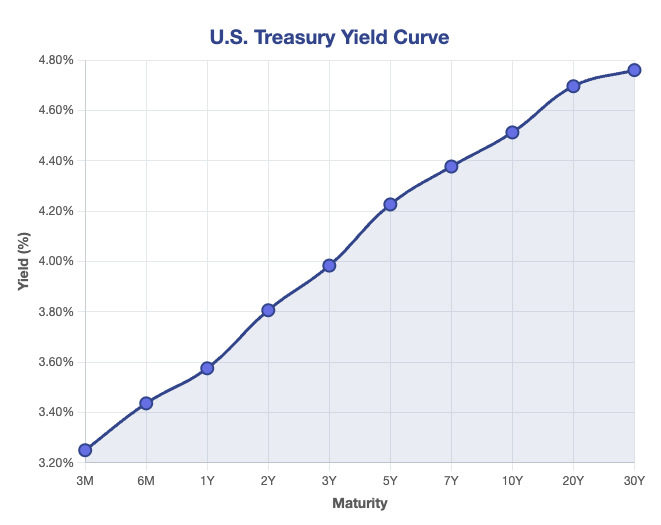

For example, going from a relatively narrow spread between short and long rates:

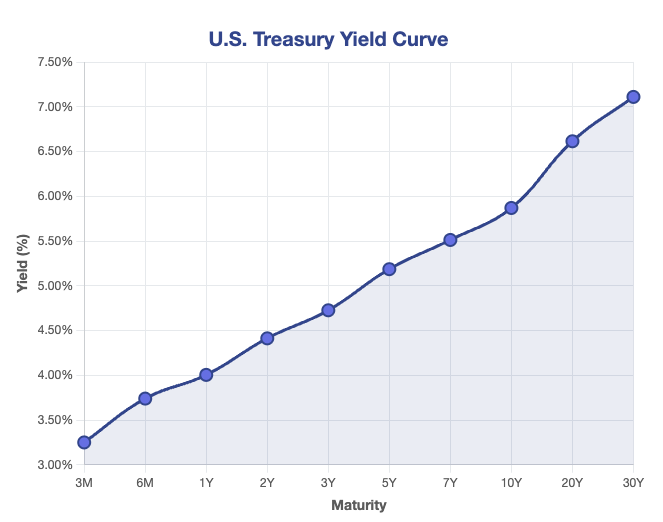

To this:

Macro setup

In a reflationary (bear) steepener, we generally see an economy emerging from a slowdown into an early- or mid-cycle recovery. Growth momentum is improving faster than policy normalization.

Fiscal stimulus, infrastructure spending, or supply-side constraints lift nominal growth expectations.

In turn, this tends to push up inflation risk premia.

As a result, traders demand higher compensation at the long end of the curve, driving term premia higher.

The central bank retains credibility at the front end (policy rates remain anchored by guidance and institutional trust).

This allows long rates to rise without an immediate repricing of short-term rates.

Typical expressions

Typical reflationary steepener expressions focus on benefiting from rising long-end yields while the front end remains policy-anchored.

A common structure is a swap steepener.

A swap steepener involves paying fixed in 10-year rates while receiving fixed in 2-year rates, directly capturing curve widening.

In cash or futures terms, traders may run short duration in the long end and long duration in the front end, isolating slope rather than outright rate risk.

These trades are often complemented by long inflation breakevens alongside a long curve slope.

This aligns higher term premia with improving nominal growth and inflation dynamics.

Example

This can be done with Treasury futures.

Position:

- Short 10-year Treasury futures (e.g., ZN)

- Long 2-year Treasury futures (e.g., ZT)

Sizing = DV01 (Dollar Value of a 01 basis point move)-matched to isolate slope. ZN is more volatile than ZT because of duration, so ZT will be help in larger quantity so it’s duration-matched. Can also be beta-matched. (We’ll explore this more later in the article.)

What makes money = Long-end yields rise while front-end remains anchored.

Macro logic

This is the “growth beats policy” regime.

Markets demand compensation for inflation risk and fiscal supply, while policy rates lag.

Historically, this appears after deep slowdowns when balance sheets are repaired but nominal growth reaccelerates.

2) Policy-Pivot (Bull) Steepeners

Mechanism

Short rates fall faster than long rates.

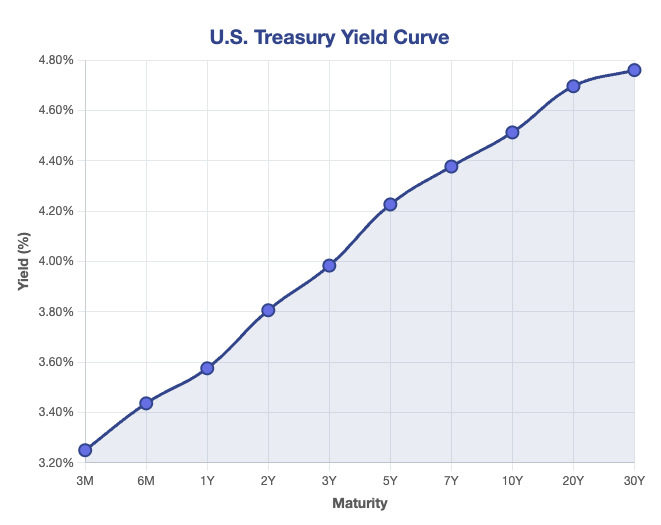

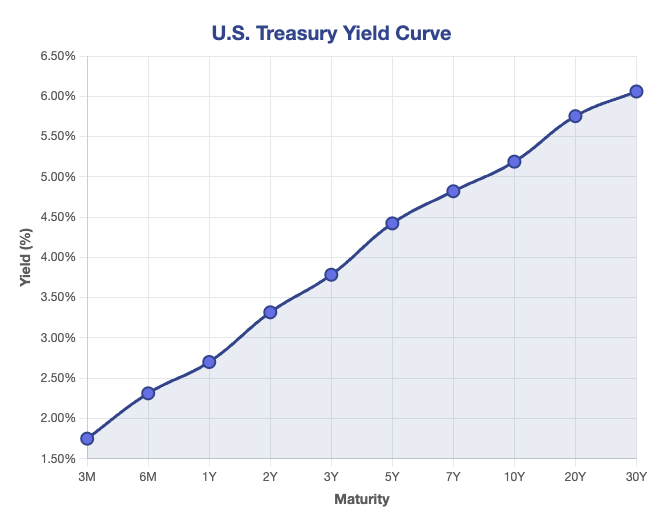

From this:

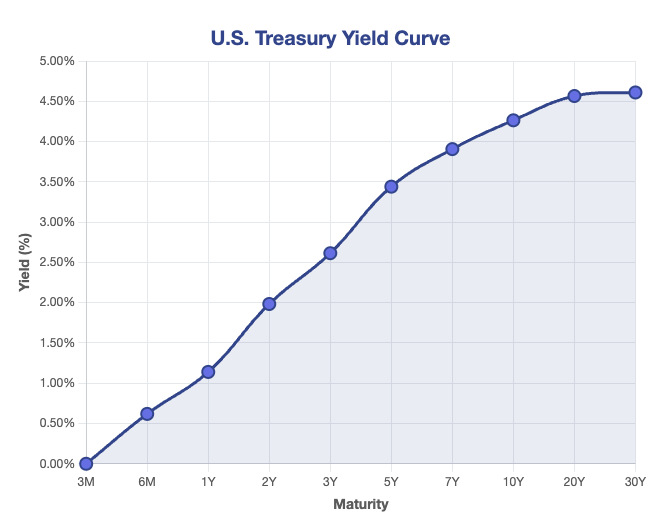

To this:

Macro setup

Here the macro environment is generally defined by a late-cycle slowdown or outright recession, where growth decelerates faster than inflation fully normalizes.

Financial conditions tighten, labor markets soften, and downside risks to activity force the central bank to shift to an easing bias.

The idea is to cut policy rates to stabilize demand.

Short-dated yields fall as markets price aggressive easing.

However, long-term rates prove comparatively sticky.

Factors like elevated public debt, large fiscal deficits, and heavy bond supply anchor concerns about long-run debt sustainability, which prevent a parallel collapse in long yields.

The result is a bull steepening driven by front-end relief rather than renewed optimism – i.e., a market that believes policy has to ease, but remains skeptical that the economy can return to a low-rate, low-debt (at least relative to output) equilibrium.

Typical expressions

Typical policy-pivot steepener expressions are designed to benefit from falling short-term rates – while limiting exposure to the long-end.

The core trade is to a) receive front-end rates – e.g., the 2-year and b) remain neutral or modestly short in the long end.

This isolates curve steepening rather than outright duration.

Receiver spreads on the front end are often preferred. This is because they can capture aggressive easing scenarios with defined downside if cuts are delayed.

In cash markets, traders typically position long bills or 2-year bonds and short 10- to 30-year maturities.

This has to do with confidence in near-term policy easing but also skepticism that structural debt pressures will allow long rates to fall commensurately.

Macro logic

This is the classic late-cycle steepener.

Policy eases, but structural forces (high debt, fiscal dominance, supply of duration) limit how far long rates can fall.

In large debt cycles, these steepeners often precede currency pressure rather than a clean return to secular disinflation.

The sell-off of the long end of the curve is a popular debasement trade.

Key risk

Flight-to-quality that drags long rates sharply lower, flattening instead of steepening.

3) Fiscal-Dominance Steepeners

Mechanism

Term premium ↑ despite easing growth

Macro setup

In a fiscal-dominance steepener, the macro backdrop is shaped by heavy sovereign issuance that overwhelms private demand for duration.

Large, expanding structural deficits and refinancing needs force governments to continuously tap bond markets. This pushes up long-term yields regardless of cyclical growth conditions.

At the same time, the central bank becomes constrained, either:

- politically, due to inflation optics and public scrutiny, or

- financially, due to balance-sheet losses and credibility risks

This, in turn, limits its willingness or ability to suppress long rates.

As these pressures build, markets begin to price rising probabilities of debt monetization (the central bank buying its own debt), financial repression (suppressing yields to manage debt), or inflationary resolution rather than orthodox tightening.

The yield curve steepens not because growth is accelerating, but because confidence in the long-term purchasing power of money and debt erodes.

This regime is historically unstable. It often precedes currency weakness, regulatory/political intervention, or explicit yield curve control.

(Related: Yield Curve Control Trading Strategies)

Typical expressions

Typical fiscal-dominance steepener expressions focus on protecting against rising term premia and erosion of real value at the long end.

Traders often short nominal long-duration bonds while remaining long inflation hedges, such as breakevens or real assets.

This is about monetization risk rather than cyclical growth.

Curve steepeners are frequently paired with FX or commodity hedges. Gold, of course, is a major one here. This acknowledges that fiscal stress can spill into currency weakness or higher goods inflation.

More structurally, cross-market steepeners are used (positioning for curves to steepen in fiscally weaker countries relative to stronger peers).

This can capture divergence in debt credibility.

These trades are less about timing policy cycles and more about expressing regime-level risk around sovereign balance sheets.

Macro logic

When debt dynamics dominate, the curve steepens because confidence erodes at the long end, not because growth is strong.

Historically, this regime is unstable: it can morph into currency weakness, inflation, capital controls, or financial repression.

Key risk

Sudden yield-curve control or regulatory suppression of long rates.

4) Tactical vs Structural Steepeners

Tactical

Tactical steepeners are event-driven (data surprises, policy meetings, auctions).

Best via options to cap downside.

Structural

Best via diversified expressions – rates, inflation, FX, real assets.

This is because a structural steepener expresses a regime shift, not a single policy event.

As a result, it’s built across assets.

For example:

Rates

Curve steepener (e.g., receive 2y / pay 10y or short 10y vs long 2y futures).

Inflation

Long breakevens or TIPS to capture rising inflation risk and term premium.

FX

Short the currency of the fiscally weaker country vs a stronger peer or real-asset FX.

Also, long gold as an “inverse currency.”

Real assets

Long commodities (energy, metals) or infrastructure-linked equities.

The logic is that if disinflation is ending or fiscal dominance is rising, pressure shows up simultaneously in the curve, inflation pricing, currency, and real assets.

The diversification reduces your reliance on any single policy path and can better capture the theme holistically.

Related: Debasement Trade

Nuances of the Steepener Trade

1. The Cost of Carry (“The Bleed vs. The Paycheck”)

A steepener goes beyond a directional bet.

It’s a position that either pays you or costs you money every day you hold it. It depends on the current shape of the curve.

Inverted Curve Context

If the yield curve is inverted (e.g., 2-year yield is 5% and 10-year yield is 4%), a steepener (Long 2Y / Short 10Y) has positive carry.

You are receiving the higher 5% yield and paying the lower 4% yield. You are “paid to wait” for the normalization.

Normal Curve Context

If the curve is upward sloping (normal), a steepener has negative carry.

You’re receiving a low short-term rate and paying a high long-term rate.

The market must move in your favor in a sufficient enough timeframe, or the “bleed” will eat your profits.

Why it matters

Consider calculating the “breakeven” days – namely, how long you can hold the trade before the negative carry wipes out the projected PnL of the move.

It’s the same concept with shorting a bond. Let’s say the bond yields 4% (pay 4% per year if shorting) and inflation is 3%.

That means you need a 7% drop in the price just to get a 0% real return.

2. Beta-Weighting vs. DV01 Matching

Doing the trade DV01-matched assumes a 1:1 correlation where, e.g., the 2-year and 10-year yields move by the same amount.

But one end can be much more volatile than the long end during a pivot.

The Adjustment

Traders also sometimes use Beta-Weighted Hedging. They run a regression to see how much the 10-year usually moves for every 1bp move in the 2-year.

And how steady and reliable is this regression?

The Risk

If you simply DV01 match, you might unintentionally end up with a net-long or net-short duration position because the volatility of the two points on the curve differs.

3. Convexity Risk

In a volatile rate environment, a portfolio of long 2Y bonds and short 10Y bonds has a convexity profile.

If rates move largely in either direction, the curvature of the bond pricing formulas can work for or against you.

For example, in a massive sell-off (i.e., rates up):

- the duration of your long position (2y) shortens, and

- the duration of your short position (10y) shortens less

This can potentially change your hedge ratio dynamically.

4. Specific Options Structures

There are several standard sophisticated expressions used by macro funds:

Conditional Steepeners

Buying a steepener that only activates if rates drop below a certain level.

Similar to the concept of knock-ins and knock-outs, which can add a risk management layer when you only activate the trade in a specific state of the world in which it’s most likely to be favorable to you.

Curve Caps/Floors

Options on the spread itself (e.g., CMS Spread Options), rather than options on the underlying bonds.

Swaptions

Paying a premium to enter a steepener swap at a future date (effectively betting on volatility and curve shape simultaneously).

5. The “Unwind” Mechanic

Steepening from an inversion is rarely a slow, smooth process.

It’s usually violent and driven by the “unwind” of the crowded flattener trade.

When a recession hits, the “un-inversion” often happens in a matter of weeks, not months.

So steepening is often a “snap” rather than a drift, driven more by forced position exits than by slow-moving fundamentals.

How to choose which steepener

Ask three questions before putting the trade on:

Who controls the front end?

If the central bank is unconstrained, bear steepeners are fragile.

Who absorbs duration?

If private balance sheets must absorb supply, term premium risk rises.

What breaks first: growth or credibility?

Growth breaks -> bull steepener

Credibility breaks -> fiscal steepener

Portfolio role

Curve steepeners often signal transitions between phases of the debt cycle.

Used correctly, they can hedge equity duration risk and complement your inflation protection that you might get from being long commodities, certain equities, and being long TIPS relative to nominal bonds.

Bottom line

A steepener isn’t a single trade, but a thesis about the macro regime.

Get the regime right, then pick the cleanest expression.