What Makes a Currency Overvalued or Undervalued?

When determining whether a currency is overvalued or undervalued, there is no agreed-upon framework.

While traders and governments build models to estimate equilibrium exchange rates, reality is more nuanced – currencies can remain misaligned for years due to politics, policy choices, structural imbalances, regulations, frictions, and other factors.

Let’s break down what influences currency misvaluation, what signs to look for, and how global forces keep certain currencies strong or weak despite what theory says should happen.

Key Takeaways – What Makes a Currency Overvalued or Undervalued?

- Valuation ≠ Price – A currency is overvalued when it buys more than economic fundamentals justify; undervalued when it buys less.

- Trade Imbalances Matter – Persistent surpluses suggest undervaluation. Chronic deficits hint at overvaluation, especially when not corrected over time.

- REER, PPP, BEER, and FEER et al Are Simply Models – Models guide traders but often disagree, especially during long misalignments.

- Distortions Are Common – Capital flows, sentiment shifts, and central bank interventions can override fundamentals for years.

- Misalignments Create Edge – When policy, reserves, and fundamentals diverge, expect volatility – ideal for asymmetric macro trades. Timing is everything.

Understanding Currency Valuation

What Does It Mean for a Currency to Be Overvalued or Undervalued?

A currency is overvalued when its exchange rate is higher than what would be justified by economic fundamentals.

That means its purchasing power abroad is artificially high – it buys more foreign goods or services than it “should.”

On the flip side, a currency is undervalued when it trades below its fundamental value, making a country’s exports cheaper and more competitive globally.

In practice, determining that “should” is difficult.

Economists use a mix of models, ranging from purchasing power parity (PPP) to current account-based assessments, interest rate differentials, and behavioral equilibrium exchange rate models.

Each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

We cover these models more below (and list the factors and macro relationships influencing FX trades here).

Key Drivers of Currency Misvaluation

1. Trade Balances and Current Accounts

One of the clearest long-term signals of misvaluation is a persistent imbalance in a country’s current account, which includes trade in goods and services, income flows, and transfers.

A consistently large surplus suggests the country is exporting far more than it imports – often because its currency is undervalued and makes its goods artificially cheap abroad.

A chronic deficit might mean the opposite.

Countries like China, with significant and ongoing trade surpluses, often come under scrutiny for currency undervaluation.

In contrast, countries running large deficits may face claims that their currencies are overvalued and dampening export competitiveness.

2. Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER)

The Real Effective Exchange Rate adjusts a country’s currency value for inflation and trade relationships with multiple partners.

If a country’s REER is consistently falling, while its economy grows robustly and exports surge, the currency may be undervalued.

Conversely, a rising REER in a sluggish economy can indicate overvaluation.

REER captures more nuance than a simple USD or EUR exchange rate. It accounts for how a currency performs across a basket of partners, and it’s often more revealing of deeper valuation trends.

Valuation Frameworks

Some of the most common FX valuation frameworks:

Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER)

As mentioned, REER helps understand international price competitiveness.

A depreciation in the REER implies a country’s goods become cheaper globally, boosting exports.

Conversely, a higher REER suggests loss of competitiveness.

REER is sensitive to shifts in trade relationships – e.g., movements in a heavily weighted currency (like the euro for the USD) matter more than those with minor trade ties.

Traders monitor REER for mean-reversion opportunities, especially in export-driven economies or during policy misalignments.

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

PPP compares the price of a standard basket of goods between two countries.

If a Big Mac costs $5 in the US and equivalent goods cost $3 in another country, PPP theory suggests that the foreign currency is undervalued by 40%.

While intuitive, PPP is a long-run model and tends to oversimplify.

It ignores trade restrictions, non-tradable goods, services, and income level differences. Still, it’s a useful directional metric.

So, PPP alone won’t time trades but helps frame relative misalignment.

Behavioral Equilibrium Exchange Rate (BEER)

The Behavioral Equilibrium Exchange Rate (BEER) model estimates a currency’s fair value based on current macroeconomic fundamentals relative to their long-run sustainable levels.

Unlike static models like PPP, BEER is dynamic and captures the impact of cyclical, structural, and transitory factors.

These may include interest rate differentials, productivity gaps, terms of trade, fiscal balances, and net foreign asset positions.

The model often uses econometric techniques, making it adaptable but also sensitive to variable selection and model assumptions.

BEER recognizes that currencies don’t always trade at equilibrium but fluctuate around it due to sentiment, shocks, and policy shifts.

Traders use BEER to gauge whether a currency is over- or undervalued and to position for medium-term mean reversion.

It’s especially valuable after major macro events, i.e., such as elections, rate hikes, or trade disruptions, when markets overshoot fundamentals.

Fundamental Equilibrium Exchange Rate (FEER)

FEER reflects the exchange rate that stabilizes a country’s external position (i.e., current account) over the medium term, assuming policy consistency.

It identifies misalignments when persistent deficits or surpluses signal over- or undervaluation.

FEER is useful for long-term investors assessing whether a country can sustain its fiscal and trade balance without crisis or intervention.

However, estimating FEER is complex – reliant on assumptions about productivity growth, capital mobility, and reserve adequacy.

For macro traders, FEER is a structural gauge best used with a longer-term outlook.

Macroeconomic Balance (MB)

This method estimates the current account balance that would be consistent with a country’s fundamentals – like demographics, productivity, and fiscal policy – then compares it to the actual balance.

The gap helps estimate how much the exchange rate would need to change to bring the two in alignment.

If, for instance, the model says a country should have a surplus of 0.5% of GDP, but it’s running a 3.5% surplus, that suggests a significantly undervalued currency.

The macro-balance approach avoids “normalizing” misalignments by focusing on structural fundamentals rather than trends.

MB is favored by the IMF and central banks for policy guidance.

Traders can use MB to anticipate regime shifts or currency adjustments when fundamentals diverge significantly from current account performance, especially in countries facing twin deficits (current and fiscal) or boom-bust capital flows.

Global Exchange Rate Assessment Framework (GERAF)

GERAF, developed by the US Treasury, enhances IMF models by integrating safe-haven demand, capital account openness, and policy distortions.

It evaluates misalignments across 50+ countries using a sophisticated model of current account gaps, then translates these into real exchange rate deviations.

Unique inputs include institutional strength, aging demographics, and FX interventions.

GERAF is valuable for traders looking at systemic FX risks and country-level divergences, particularly where policy distortions (like capital controls or FX reserves buildup) skew typical valuation models.

It excels in evaluating multilateral consistency in global FX shifts.

Market Forces That Distort Currency Valuation

1. Capital Flows and “Sentiment”

Currencies don’t just reflect trade activity – they’re also driven by capital flows.

A surge of foreign investment into a country can drive up its currency, regardless of trade deficits.

Likewise, capital flight can cause a currency to fall even if trade is in balance.

If investors believe a country is politically unstable or economically risky, its currency may weaken beyond what fundamentals suggest.

Fear and speculation can override logic in the short to medium term.

2. Government Intervention and Exchange Rate Policies

Many countries don’t let their currencies float freely. Central banks intervene by buying or selling currency, adjusting interest rates, or using regulatory measures to guide exchange rates.

These interventions can create artificial values that deviate from market-determined levels.

For example, China has historically intervened – sometimes directly, sometimes through state banks – to keep the renminbi (RMB) stable or weak, even amid growing trade surpluses.

This kind of managed exchange rate can result in long-standing undervaluation, especially when capital controls prevent market forces from correcting it.

Persistent Misalignments: Why They Happen

1. Structural Policy Choices

A country might choose to keep its currency undervalued to drive export-led growth.

By maintaining a weaker currency, it keeps labor-intensive goods cheap for foreign buyers.

Over time, this can lead to huge foreign exchange reserves, large current account surpluses, and growing political tension with trade partners.

Alternatively, some countries with overvalued currencies are unwilling – or unable – to adjust due to political risks, fear of inflation, or reliance on imports priced in foreign currency.

2. Commodity Prices and Resource Dependence

Commodity-exporting countries – like Brazil, Norway, or Saudi Arabia – often see their currencies rise during commodity booms and fall during busts, regardless of underlying productivity.

If prices collapse but the exchange rate doesn’t adjust downward enough, the currency may become overvalued, making non-commodity exports uncompetitive.

Misleading Appearances: Why Models Don’t Always Agree

A key challenge in valuation is that most models tend to rationalize persistent misalignments.

If a country runs large trade surpluses for a decade, models may begin to assume that this is the new normal, eroding the case for undervaluation.

That’s why more dynamic frameworks – like the macro-balance approach – are helpful.

They attempt to factor in lagging variables like previous exchange rate movements and business cycle positions, while resisting the urge to accept long-term distortions as “fair value.”

Free-Floating vs. Pegged Exchange Rate Systems

A country should allow its exchange rate to float freely when it has strong institutions, deep financial markets, and a diversified export base, as in more advanced economies.

Floating rates give monetary policy autonomy – critical when domestic inflation control or economic stabilization is the priority.

Conversely, pegging is often suitable for developing economies reliant on external trade, especially when inflation expectations are unanchored or financial credibility is weak.

Pegs are typically fixed to the currency of a top trade partner or the global reserve currency (i.e., most commonly pegs occur to the US dollar, but also the EUR to a lesser extent) to stabilize import prices.

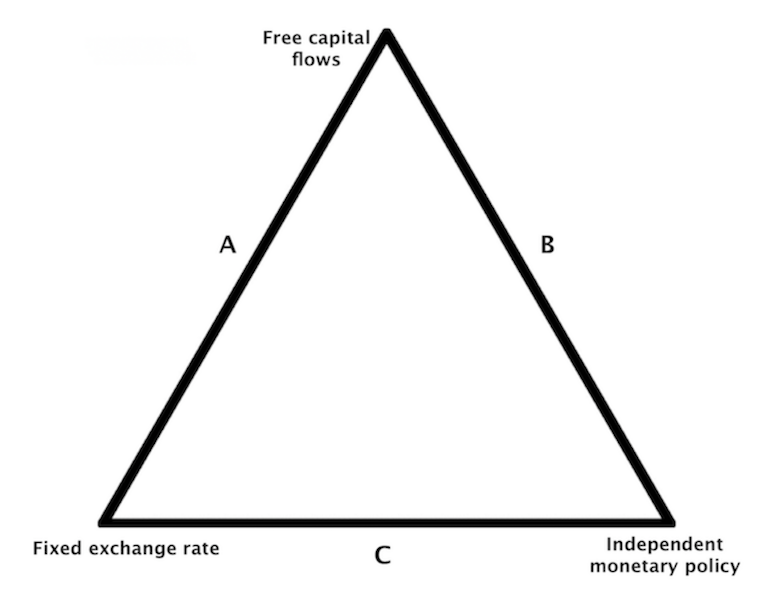

This decision is deeply constrained by the “impossible trinity” or monetary trilemma: a nation cannot simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement, and independent monetary policy. It can only choose two.

Pegging is more common in early development stages, where capital inflows are critical and inflation control through credibility is essential.

Floating becomes feasible as institutions mature and resilience grows. Traders look to such events for profitable currency trades.

The Conditions Where Breaking a Peg Is Likely

Breaking a currency peg typically occurs under mounting macroeconomic imbalances that make maintaining the fixed rate unsustainable.

Watch for persistent current account deficits, rapidly declining foreign exchange reserves, and rising inflation – especially when the central bank is defending the peg through aggressive rate hikes or intervention.

Political resistance to austerity or reforms often signals limited willingness to adjust fundamentals, increasing the odds of a disorderly break.

Key triggers include speculative attacks when traders perceive the peg is misaligned with fundamentals, especially if real interest rates are negative and reserves are being depleted.

High external debt in foreign currency amplifies pressure, as debt service costs soar under strain.

Traders should monitor signals like reserve adequacy ratios, parallel market rates diverging from official rates, IMF engagement, and capital controls.

Peg breaks are often abrupt, high-volatility events – ideal for asymmetric trades if positioning is early and risk is defined.

The key is timing the policy capitulation.

For example, if a country is planning to depreciate its currency, this may show up in the form of paying off debt denominated in foreign currencies (i.e., before the exchange rate goes against them).

Real-World Examples

China’s Renminbi (RMB)

China is often cited as an example of prolonged currency undervaluation.

Despite rapid economic growth, the RMB has depreciated in recent years even as China’s trade surplus in non-commodity goods has grown.

While many currencies depreciated due to commodity shocks or monetary policy shifts, China’s trade-weighted REER decline, alongside a strong current account, suggests deliberate undervaluation.

Estimates using macro-balance methods indicate that the RMB may be undervalued by over 10% – possibly more than 20% depending on how you define current account equilibrium.

This disconnect between theory (which sees pressure to depreciate) and reality (large surplus, strong export performance) shows that currency valuation is a complex thing.

Why It Matters

Misaligned currencies can distort global trade, fuel economic tensions, and create unfair competitive advantages.

Undervalued currencies boost exports but can spark accusations of currency manipulation.

Overvalued currencies hurt domestic producers, stoke current account deficits, and lead to external debt build-up.

Understanding the factors that make a currency overvalued or undervalued helps governments design smarter policy, businesses hedge risk, and traders assess opportunity.

But ultimately, currency valuation is a moving target – shaped by a web of economic logic, market psychology, and political will.