Swap Rates vs. Bond Yields

The swap rate market gained widespread institutional popularity during the 1980s. Reportedly, IBM and the World Bank completed the first modern swap agreement in 1981. Today, hundreds of trillions of dollars’ worth of swaps are outstanding – many multiples of world GDP of some $88 trillion – making them among the most traded financial instruments in the world.

Swaps are derivative contracts in which two counterparties exchange the cash flows of each party’s financial instrument. This means they are usually custom-made for each party and traded “over the counter” (OTC). Certain exchanges, such as the CBOE, CME, and ICE, all support OTC swap trading on their platforms for the standard arrangements in these instruments (e.g., swaps pertaining to US Treasury bonds).

Swaps most commonly apply to bonds, interest rates, and currencies. They are used to either speculate on the direction of the price of the underlying instrument (typical among hedge funds and other types of traders). Or they can be used to hedge out certain types of risks, commonly pertaining to interest rates or FX, which is more common among corporate participants to hedge out their financial related liabilities. There are also swaps designed to speculate on or hedge out the risk associated with certain commodity or equity prices.

In the case of a swap involving two different bonds, the form of cash flow exchange heavily depends on the coupon payment associated with these bonds.

The swap agreement itself will specify which cash flows are to be paid by what date, and how they will be calculated and accrued. There is usually some type of floating or variable rate associated with swap contracts, usually a reference rate (e.g., LIBOR) that is determined by an independent third party.

The notional principal amount of the underlying instrument is typically not exchanged between counterparties. This makes swaps unique relative to other contracts, such as options, forwards, and futures.

Swap rates vs. Bond yields

For swaps that pertain to fixed income cash flow exchanges, swap rates typically trade at a premium over their corresponding bond yields. Treasury bonds have corresponding swap rates, and these swap rates have historically traded at a premium over Treasury yields.

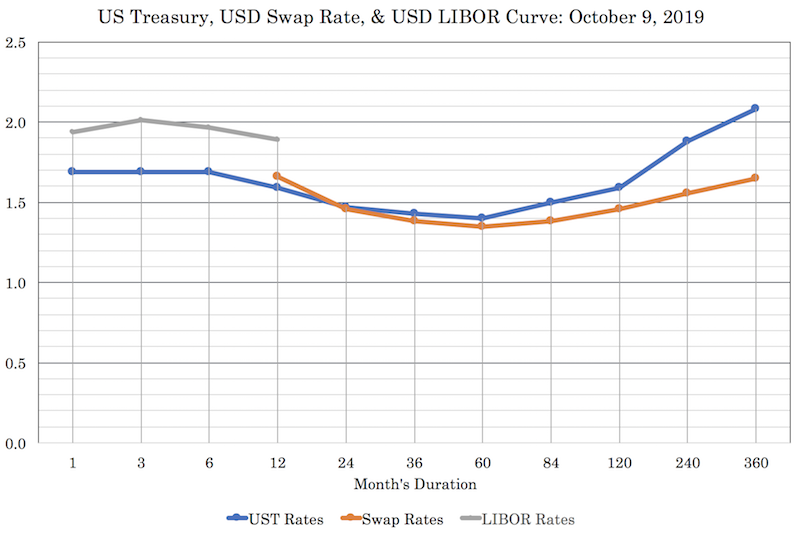

However, if we look at the US Treasury and USD swap rate curves, we see the Treasury curve being above the swap curve for all durations beyond two years (24 months).

This negative spread is a whopping 43bps on the 30-year duration. Traditionally, it doesn’t make sense that buying a security from the government would be more risky than buying the same type of security underwritten by a commercial, investment, or merchant bank, or independent swap underwriter. The US government is more creditworthy than any given entity that can write a swap for you.

Theoretically, the extra risk premium for a US Treasury swap over the corresponding bond is a few basis points. This represents the extra compensation expected for the marginally higher likelihood that the swap’s underwriter will default in comparison to the federal government defaulting on a debt maturity.

You would think that this fundamental relationship doesn’t make sense and would theoretically reverse. And if something is mispriced, then you could trade it (i.e., short “overvalued” US Treasury swap, long “undervalued” corresponding US Treasury futures contract).

But prices can remain out of whack for rational reasons even if the fundamental cause doesn’t seem right.

So, why has the negative relationship become so endemic to the US Treasury curve?

These days, banks have higher capital requirements, less latitude on what they can hold on their balance sheets, and a more stringent regulatory environment as a whole. Companies that issue debt also have an outsized role in the swap market. Corporations and institutional traders use swap contracts to exchange fixed rates for floating rates. When a company sells debt at a fixed rate, it can contact an investment bank to design a swap to help the company pay a lower floating rate, such as a short-term reference rate (e.g., three-month LIBOR).

Moreover, market makers (also known as dealers, and comprise large financial institutions) are having to sell larger quantities of Treasury bonds to their clients. This keeps their inventories of these securities higher.

Treasury bond and swap trading is also heavily intertwined in the repurchase (“repo”) market. The use of repurchase agreements to buy Treasuries is also shrinking among market makers. This helps to push up demand for swaps instead, which lowers their yields relative to the underlying bonds. Naturally, as capital and balance sheet capacity decrease in availability, banks have decided to reduce their repo books given the balance sheet intensive nature and thin margins of the business. Banks have to be more selective, and this means doing fewer transactions in less profitable areas.

Accordingly, traders are no longer as able to use the repo funding market to buy US Treasuries and pay the fixed rate (and receive the floating rate) on a swap. If a bank were to enter into that trade, the repo transaction would consume capital on its balance sheet, which it can’t afford if regulation constricts bank capital and how much of what they can and can’t hold in various forms.

All of this activity has the effect of pushing demand away from Treasury cash bonds and toward swaps as instruments of speculation. Holding all else equal, more demand means higher prices, and higher prices means lower yields.

Moreover, as the US fiscal deficit climbs, both in gross terms and as a proportion of GDP, tighter bank regulation increases gross funding costs for the US government.

In a typical free market, where supply and demand meet at a certain price unimpeded by exogenous forces, Treasury swap market inversions would be reversed. But with more stringent bank capital regulations, the counterintuitive relationship where higher-credit-risk swaps have lower yields than “risk free” Treasury bonds has become the new norm.

Takeaway

Most retail / individual traders don’t have access to the swaps market (though Interactive Brokers offers some exposure to swaps on Treasury futures). But the general point is not just the unusual relationship in this particular niche of finance, but rather the idea that just because something seems fundamentally out of whack (and therefore ripe to exploit) doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily a good trade idea.

Anyone who follows the markets is probably aware of the storyline of how “value investing” has become either “ineffective” or “out of style” in some form.

While buying something that’s notionally undervalued is good in theory, movements in financial markets are based on buying and selling activity, and clearly that’s not always based on strict adherence of what something is theoretically worth. In all markets, there are different buyers and sellers of different sizes and various motivations. While some markets may be more expensive or cheaper than others, they can remain that way for long periods of time. Some markets, such as cryptocurrencies, have little to do with value and are more speculative pursuits.

Shorting a higher-credit-risk security and going long its equivalent corresponding lower-credit-risk counterpart sounds good in theory as a relative value opportunity. However, in the case of the US Treasury swap market there is an underlying reason why this spread is backwards and out of line with its putative equilibrium value.

No matter what the market is, when something doesn’t make sense fundamentally, always question whether you are missing something and why other players in the market – all looking for the same forms of money-making opportunities – haven’t already exploited a seemingly obvious trade.