Are Cryptocurrencies Worth Owning in Volatile Markets?

Cryptocurrencies are a fledgling asset class that has produced, and is continuing to produce, mainstream speculative interest. Their widespread run-up in price throughout 2017 brought large-scale public attention.

However, whether you’re a day trader, active swing trader, or buy-and-hold investor, trading is a business. In order to trade well, you have to know asset classes well enough to understand where they might go moving forward or how to structure them in a portfolio such that they enhance return and/or reduce risk as part of a broad diversified approach.

You have to have a deep understanding of what makes an asset class move – both how it trades fundamentally and who the main buyers and sellers are and what their motivations could be broadly represented as. That will give you an indication of how it’s expected to trade (e.g., its volatility, when it does well, when it does poorly, what its expected returns are). And you need to be able to do this better than the average market participant either through an information or analytical edge.

For now, cryptocurrencies have been mostly conjectural, speculative instruments that most people put money into because they expect that somebody else will buy it from them at a higher price. That’s pure speculation or the “greater fool theory”, which creates a large amount of volatility in its price.

Nobody knows their exact worth and many of these markets are not particularly liquid, which is what creates the large swings in price. There are no cash flows that can be analyzed (i.e., stocks, bonds), no interest rates that can be compared (e.g., one currency relative to another), and no quality supply and demand analyses can be done (e.g., commodities).

There is the standard regulatory risk to cryptocurrencies. Governments have an influence on whether they are, or will remain, viable as a means of payment even as off-the-grid payments systems. At various points throughout history, governments outlawed gold ownership (a form of foreign exchange control) to curtail outflows of capital that reduce the value of their currency.

For any given cryptocurrency to do well, they must be engineered in a way that makes them attractive. For instance, having the following qualities:

– Easy for people to get on the network and get access to

– Easy to convert into from other currency forms

– Easy to transact in

– Widespread acceptance as a means of payment money

– Stable in value

– Cannot be easily copied, replaced, created, or destroyed

Bitcoin is the most popular cryptocurrency and has been from the beginning as the pioneer in the space. Nonetheless, it’s had, and continues to have, the following problems plaguing its widespread adoption:

– Easy to copy (there are thousands of other “coin” variants)

– Too many speculators, which creates a large variance in its value

– Dubious value as a currency (too volatile to be a store-hold of wealth to go along with limited transactional utility)

– Dubious value as an investment; it doesn’t reliably defer consumption to the future

Nonetheless, bitcoin has first-mover status and established futures markets, both of which help to imbue it with value.

Current Lessons for Policymakers on the Cryptocurrencies Phenomenon

Cryptocurrencies are not simply another random conduit for speculative activity. The phenomenon has broader economic meaning even if much of the market doesn’t have a ton of rationality behind it.

The lesson for policymakers is that our payments systems are too slow and cross-border transactions are inefficient. The ACH system in the United States takes 1-3 days. Getting payments through the SWIFT system can take up to a week and sometimes longer. Payments often involve heavy costs. Vested banking and financial interests have largely impaired innovation in our payments systems. Money should be able to travel as fast as information does, yet it still takes days through the most popular channels. Banks prefer the current system because it generates interest and fees.

This inconvenience in the traditional way of doing things gives cryptocurrencies value and has helped popularize them. Cryptocurrency transfers can be instant, or close to instant, and are also (normally) cheaper.

Do More Cryptocurrency Transactions Boost Their Prices?

More people using cryptocurrencies to transfer funds does not, however, do much to impact their prices directly.

Once people receive a crypto payment, what do they almost always do? They convert it back into their domestic currency. That involves one person buying crypto, and another selling it. There is no net effect on the price.

It doesn’t matter if there are a billion bitcoin / cryptocurrency transactions. If an equal amount is bought and sold, it won’t make a difference if there is no permanent conversion from the fiat currency (or another cryptocurrency) into the cryptocurrency facilitating the transaction.

For example, let’s say someone in the US buys something from Germany. They don’t want to do a bank wire and use bitcoin (or another cryptocurrency) instead.

The German is going to take the American’s bitcoin and convert it back to euros. There’s no influence on the price of bitcoin unless the German keeps the currency in bitcoin, which is highly unlikely if he’s not a speculator. The only relative value effect is on the USD and EUR, not the bridge currency (bitcoin). (It represents a capital outflow for the US (German export, US import), thus the transaction would do its small part in boosting the euro relative to the US dollar.)

Any positive price effect on the cryptocurrency is less direct, coming in the form of higher inflows from more people and other entities believing in its capacity to act as a store-hold of value and an effective means of exchange.

Cryptocurrencies are not at that stage in their development. They are not yet at the point where the big players in the market have a material impact on their prices. This is because of their lack of structural robustness. Namely, they are not yet relevant as store-holds of wealth either as reserves (i.e., how central banks would view them) or as currencies and currency hedges to protect against low rates and monetizations of national currencies (i.e., why institutional investors would show interest). They don’t matter yet at that level and have a long way to get there.

Moreover, people use the past to determine how asset classes will behave going forward.

Cryptocurrencies do not have the track records of the US dollar, other developed market currencies, or something like gold. Therefore, policymakers and investors don’t know how it’ll perform in down or volatile markets. With a longer track record, and if cryptocurrencies can act as a risk-off hedge, they’ll see more attraction beyond retail speculation.

However, that future, if it ever comes, is very far away given the extreme volatility. Good store-holds of wealth do not move around in price to the extent cryptocurrencies do.

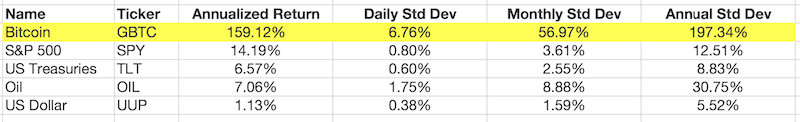

The chart below compares bitcoin’s volatility to that of mainstream assets – the S&P 500, US Treasuries (average duration of 20 years), crude oil, and the US dollar – from December 1, 2016 to the present (almost three years):

Quality store-holds of wealth do not have 11x the annualized volatility of US stocks, 24x the volatility of US Treasury long bonds, 23x the volatility of oil, and 141x the volatility of the US dollar.

For cryptocurrencies going forward, it will heavily depend on how they’re engineered. All financial assets have an environmental bias, and some will act differently from others.

For example, the Japanese yen (JPY) is typically going to act quite a bit differently than the Australian dollar (AUD) even though they are both Asian Pacific currencies. The yen is a more commonly held currency by central banks and institutional investors. The Japanese economy is larger than Australia’s and the yen has “risk off” properties, unlike the Australian dollar, which tends to correlate with the business cycle given its export base is heavily concentrated in industrial commodities.

Even well-established store-holds of wealth like gold, which has a track record going back millennia, has its own issues. Gold is not a particularly deep market in terms of size. It is only about 3 percent of the size of global equities markets and some 1 to 2 percent of the size of global debt markets. It has limited capacity to take in large wealth transfers from more traditional asset markets as a consequence of this smaller size and its relative illiquidity. However, it functions reasonably well as a reserve asset for smaller amounts of money.

Conclusion

Can cryptocurrencies be a risk-off hedge or a viable diversification item for volatile or down-trending markets?

In their present form, cryptocurrencies do a poor job of this. The buyers and sellers in these markets are mostly speculators. They are not the types of serious investors that would own them for purposes of establishing foreign currency reserves or using them as currency hedges or alternative currencies.

Trading cryptocurrencies in their current incarnation amounts to almost pure speculation. In the run-up in price in 2017 (and other runs before and since) it was largely a game of “hot potato”. It was a speculative bubble where people were betting on the idea that they could make a quick buck because of the rapid movement in the price (mostly upward) and flip it to somebody else before they got burned. Or, because it’s price had gone up so quickly, basic extrapolation of the past told them that that behavior was likely to continue.

Some might view it as a “bet on the future” – i.e., that cryptocurrencies are in their infancy and will develop into popular mainstream assets in time. But this merely conjectural. Central bankers and large institutional investors cannot validate their use in a portfolio with their current properties and turbulent price action.

Maybe someday they will be viable enough with the following properties or qualities: a robust network, reasonably liquid, easy to transact in, used broadly as a means of payment in transactions, stably valued, cannot be viably manipulated. But cryptocurrencies do not exhibit these traits currently.