GameStop (GME) Mania: What Happened

In short, GameStop (GME) mania began when some smart retail traders started hyping up a stock on social media with some peculiar characteristics:

1. It had a low valuation.

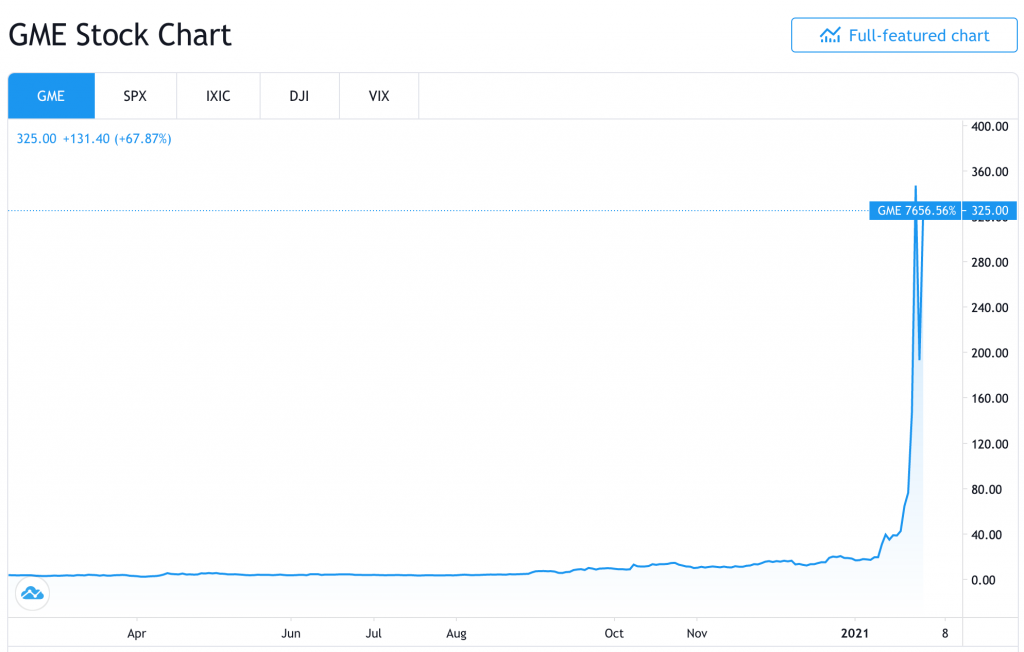

Its price reached a low of $2.57 per share. That valued the once-popular video game and consumer electronics retailer at only a couple hundred million dollars.

Many compared it to company like Blockbuster Video, a well-known entertainment brand that failed to evolve well to meet the demands of modern consumers.

2. Because of its weak economic prospects, the company was widely shorted. Certain types of institutional investors, notably hedge funds, try to pick the winners and losers.

It’s common to go long the “disrupters” and short the “disrupted”.

While the most you can gain on a standard short equity position is 100 percent, the amount you can lose can be many, many multiples. Because of this risk/reward dynamic, that sets up the potential to be “squeezed”.

It had very high (traditional) short interest (about 140%).

Short interest can exceed 100% because a single share may be lent out multiple times.

Each share sold short creates an offsetting long position. Namely, for every seller/short sale there has to be a buyer.

The net number of shares remains equal to shares outstanding.

So 140% short effectively means 240% long. This is why traditional short interest, measures as a percent of float, is flawed because it doesn’t account for synthetic longs created by short selling. These provide additional liquidity to the market. (The percent of actual shares, or net shares, lent out was 56% for GME and 14% for AMC.)

But the idea was that if you could get the share coming up off its very low prices, this would force a lot of the short exposure to unwind as they face losing potentially several multiples of their money.

Even if those shorts hedge by being long call options, it’s the same type of process. Those hedged don’t have to cover their equity exposure. But the market maker or counterparty who’s short the call needs to hedge that exposure by buying the underlying shares, which boosts the price. This is commonly called a “gamma squeeze”.

It was only a matter of getting the process going. For this, there’s social media, most notably Reddit (particularly the subreddit WallStreetBets).

Short selling

Short selling, commonly known as shorting, is difficult to do well as a standalone game because of the bias for stocks to go up over time.

People take on risk when they capitalize a company, especially as common shareholders who are most junior in the capital structure. So they expect more in return in the future.

And central banks increase the money supply and credit-creating capacity of the economy over time, which helps financial assets. Capitalist economies don’t work well when cash outperforms risk assets for extended periods of time.

Was GameStop a David vs. Goliath struggle?

That’s the way the story was commonly portrayed. The “rich vs. poor” and other “competing faction” storylines sell well, especially in a more divided environment.

While the “small guys” taking it to the “big guys” narrative helps the story reach a wide audience, it’s more complicated.

While there were some retail day traders that benefited a lot and some institutional investors that lost a lot, most of the actual wealth transfer in the GameStop (GME) market, even in the short-run, was from institutions to other institutions.

The dynamics

To better understand the dynamics, this goes back to how Robinhood and some other online brokerages generate revenue.

Brokers traditionally execute trades on behalf of their clients in exchange for a commission.

Since the rise of Robinhood this has shifted.

Robinhood is well-known for executing free trades for its customers.

How does Robinhood make money off this?

Robinhood sells its customers’ order flow to institutions, a practice known as payment for order flow (PFOF).

Institutions use this data in the process of market making. This provides liquidity to the market and helps reduce bid-ask spreads, which in turn reduces overall trading costs across the board for all market participants.

Most discount brokers route orders to market makers who will fill at the best price. Robinhood does not. They only route for a “fair price” that will give them the largest kickback.

They are transparent about this practice, as all retail brokerages have to be as a highly regulated industry.

Market makers will look to payment for order flow to give them information on what is being bought or sold and what the customer is willing to pay.

They can front-run the spread by filling the order at something other than best price by buying at one price and filling at another higher price. They can also fill basic market orders through the same process.

To do this effectively, they also need to fill the order faster than other market makers competing for the same orders.

So, payment for order flow isn’t intrinsically bad for the customer so long as the order is filled for best price.

Those who trade on Robinhood, however, need to accept that the market maker taking their order may not be filling at the best price.

To the market maker, this process largely makes money off transaction volume.

With the extremely high retail interest, institutions with market making/high-frequency trading (HFT) operations were heavily involved in these particular markets – i.e., GME, and also others including AMC, BB, EXPR, KOSS.

By leveraging the order flow data, market makers/HFTs helped amplify the volume.

How can day traders protect themselves from brokers that don’t fill for the best price?

1. Brokerages are transparent about how they route trades. As noted, they need to be for regulatory purposes. Robinhood is upfront about the way they fill trades. Trading with a brokerage that routes for best price can be a good idea.

2. Use limit orders instead of market orders. Or use a broker that has a market order routing engine that works to execute for best price (Interactive Brokers is one example).

Most of the order discrepancies between best price and any other price happens on market orders.

A market order is an instruction to trade your order at any price available in the market, subject to any additional instructions for handling or simulating the particular order type specified and other order conditions you specified when submitting the order.

A market order is not guaranteed a specific trade price and may trade at an undesirable price. If you would like greater control over the trade prices received, using a limit order makes more sense, which is an instruction to place the order at or better than the specified limit price.

On top of that, large market orders may be split into smaller orders, which will be traded over time. This is designed to reduce the impact of these large orders on the market, including the impact any given order has on the market price.

Who are the losers and winners?

The portrayal was that retail was beating hedge funds. But in reality most of the transfer was going from certain types of institutions – i.e., those short and overexposed to a rising price – toward other types of institutions, most notably those long the stock and HFTs.

Many retail traders made gains and some institutions lost, but this is always true in any public market.

Just as in the long-run, many retail traders swept up in the mania are quite likely to lose a lot when the price falls. Many of those buying at high prices, many on leverage, and trying to eventually resell it will inevitably get burned.

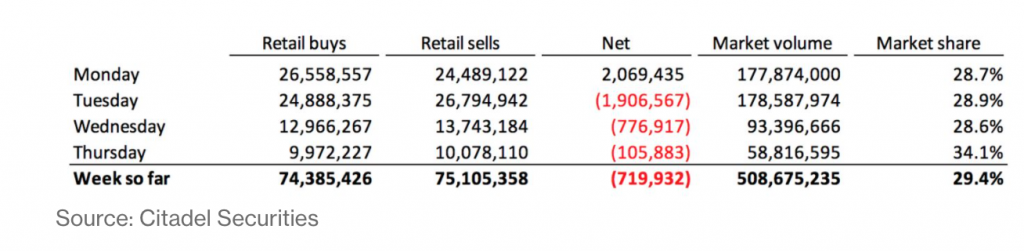

In GME’s most volatile week of trading in the last week of January, Bloomberg ran an article showing that, based on Citadel Securities’ retail flow in GME (a lot of this flow was sent from Robinhood), retail day traders’ were actually net sellers of the stock.

So, one highly plausible interpretation is that retail flow ignited the rally, but were net sellers after the first day of the week.

After that, influential directional price movements were guided largely by institutions – whether that’s hedge funds, high-frequency traders, or entities that access the markets through prime brokerage arrangements.

It’s also worth noting that GME, AMC, BB, IRBT, and others favored by smaller day traders on social media were only 0.13 percent of the S&P 500 on December 31, 2020 and only 0.17 percent on January 26, 2021.

And not even five percent of common indices of small cap stocks.

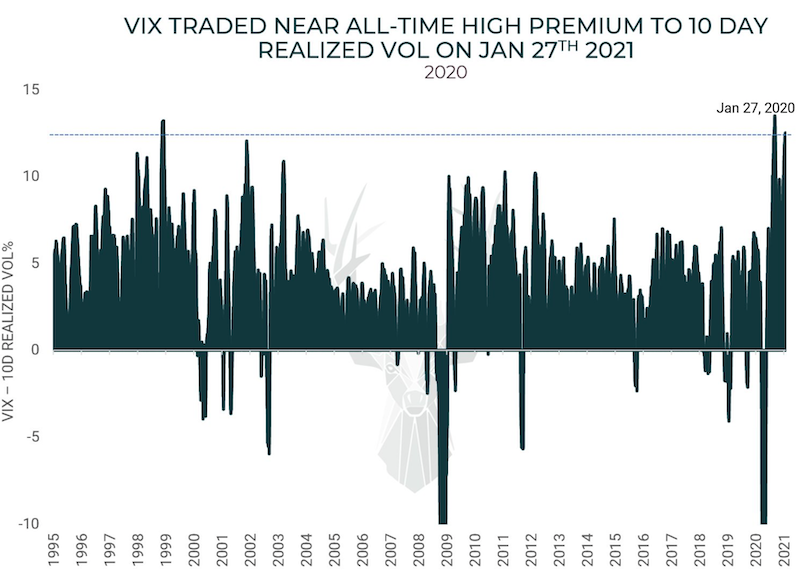

Overall market volatility during the frenzy in these stocks is still in the middle of the range it’s been at since 1928.

Getting things to go from ‘right’ to ‘wrong’

One of the more interesting aspects of the GameStop phenomenon (and AMC, among other similar bets) is that their low valuations were justified by traditional valuation reasons. But some bet that they could artificially force them to go very high.

Normally, when it comes to these types of bets, a trader or groups of traders will see something that’s unsustainable in the market and bet that it will go toward a more proper equilibrium.

Taking a few of the most popular trades of all-time:

1) Shorting of the British pound in 1992

2) Shorting Enron (ENE) in the late-1990s and early-2000s

3) Shorting mortgage-backed securities in 2007 and 2008

Traders were simply betting on what they believed would happen eventually to unsustainably high markets.

- The British pound was inconsistent with its fundamentals and would have fallen anyway.

- Enron didn’t actually make a profit or have its stated revenue total despite what their accounting said, and wasn’t the “innovative energy company” that it pretended to be.

- Consumers had taken out far too much mortgage debt relative to what could realistically be paid back.

Those in those trades believed there was a stark misallocation of capital that they thought eventually had to correct and did.

In the case of GameStop and other bets that became correlated, they saw something that was by and large right (fundamentally weak companies with low valuations) and saw if they could make them go wrong (and create a misallocation of capital).

Bubbles vs. crashes

GameStop mania emphasizes the two sides of a coin when it comes to helping broaden market access to investing, and how frequently investing gets confused with speculation.

Typically, in bubbles there’s the call to democratize access to whatever it is (e.g., tech stocks, housing) so everyone can participate in the supposedly great or even never-ending upside.

When it crashes, there’s widespread anger about what went wrong and why so many folks were left to destroy their financial livelihoods speculating in whatever it is.

Why did brokers shut down GameStop and AMC trading (among others)?

It’s helpful to know the basic plumbing between banks and brokerages.

Third-party clearinghouses are instrumental in working with individual brokerages for purposes of trade settlement.

And there are various types of lending procedures that go on between buying clients, buying brokers, selling clients, selling brokers, and the central clearinghouse.

Robinhood needs to post margin for any net unsettled activity. The higher the activity, the more of their own resources they have to post. This can drain their liquidity.

That means the broker can (and may need to) increase its margin requirements or refuse any opening trades on the security to its customers in extreme circumstances, such as high volatility or lots of new trade activity. Typically, it will allow closing trades and enable customers to hold currently open positions.

This is clearly bad for individuals in those names who can no longer open trades because of a problem with the brokerage they trade with.

This is a tail risk that happens rarely. But it’s still an important risk nonetheless in that you could end up being shut out of buying a security, or more of one that you already own.

When you buy securities with a broker, those securities are placed in the broker’s name. You can often get the securities in your own name if you want to pay extra fees.

But to have commission-free trades or low-commission trades, you essentially have only a claim on your broker and insurance on your balance up to a certain amount of money depending on the arrangement.

Helping hedge funds and institutions?

At the time there was commentary on social media and in the mainstream media about how the trading restrictions on these stocks were put into place as part of some collusive effort to help out hedge funds and other big institutions who may be shorting the stocks and losing money.

But this has everything to do with plumbing and regulatory capital constraints and was not a matter of “saving big guys”.

This widespread popularity of this simple distortion is in part illustrative of the growing intolerance people have for those who are different from them based on viewpoints or how they class themselves (e.g., the rich and the poor, the left and the right) and the desire to get at each other’s throats.

For those who want to day trade, they will need to recognize that extreme volatility can cause their broker to up margin requirements or not be able to get into certain securities in the middle of the frenzy.

It can even lead to a liquidity crisis and even the potential failure of a broker.

These restrictions applied to not only many retail brokers, but some institutional clients as well.

The role of the DTCC

Most retail traders and practically all institutional investors use margin accounts instead of cash accounts. They can buy securities in values beyond their own cash reserves.

In margin accounts, the client does not technically own the securities they have. Instead they are in the broker’s name. This makes the client essentially the broker’s creditor.

The broker used by the buyer and seller in a transaction is typically different.

So they use a third-party entity called the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC). The equity options equivalent is Options Clearing Corporation (OCC).

The brokers are DTCC’s (and OCC’s) clients.

DTCC is used to match and clear stock transactions. The title is moved from the selling broker to the buying broker and ensures that the accounting is matched up.

DTCC is both the guarantor and central repository of the title to a stock. This means the title is held in the broker’s name, not your name.

Once this settlement occurs, the transaction has cleared.

US equities clear on what’s called a “T+2” basis. This means settlement takes up to two days from the time of the trade.

However, the broker of the buyer and seller will reflect the transaction immediately as if it’s already in effect settled. This is done through lending depending on the net number of buys and sells. Any time there’s lending there’s counterparty risk.

The National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) is the entity bearing this risk, which is owned by DTCC.

DTCC guarantees settlement by using its lending capacity. At the same time, DTCC is not a big entity. So its counterparty risk has to be managed tightly in order to guarantee that transactions settle accurately.

To manage risk, NSCC demands that brokers post a clearing deposit, per Dodd-Frank.

All brokers post a clearing deposit as the extra collateral helps reduce overall systemic risk. In the event a broker fails, the NSCC will take losses out of the failed broker’s deposit, then from itself, then from all other brokers.

How these deposits are calculated involves a technical calculation involving Value-at-Risk (VaR), a gap risk measure, deposit floor calculation, and mark-to-market accounting, as the main items.

The deposits are held in the NSCC’s Clearing Fund. The financials can be found here.

The VaR calculation means that they have to post more collateral when volatility increases. Higher volatility means a wider distribution of potential outcomes and thus a higher VaR.

With the gap risk measure, if a certain stocks or group of stocks is a large fraction of their net unsettled portfolio, they must post additional collateral and this exposure can lead to a lot of downside.

If a broker’s clients are up on their positions, the mark-to-market calculation will take care of it.

But if a bunch of new positions are being opened, that creates additional resources that the broker has to post with NSCC. Moreover, if the stock falls, the broker has to post the loss before settlement occurs.

This is why Robinhood drew its credit lines to be safe in the middle of the frenzy while also increasing margin requirements and/or reducing some securities to closing-only trades.

In total, Robinhood had to capitalize itself by another $3.4 billion. That’s more than it previously raised in its existence.

Settlement guarantee is normally low-risk. But that doesn’t mean that there’s no risk at all.

Policy goals

From a policy perspective, the objective is to prevent having the most important entities from having to bear the most credit risk. Naturally, this is DTCC and NSCC, which are practically the same entity. This increases their profits.

It also raises costs to entry for brokerages. Robinhood has done well in opening up trading to the masses by pioneering the zero-commission model. But the regulations that it faces in the form of capital requirements makes it challenging.

DTCC can also set up its own margin rules on a particular stock or group of stocks on the fly, known as a Margin Liquidity Adjustment Change.

For policymakers wondering why Robinhood and other brokers had to stop its customers from buying certain securities, this has nothing to do with secret machinations and “buddy-buddy” deals and everything to do with the regulatory system requiring brokers to post collateral to cover their clients’ pre-settlement trading risk.

For many retail traders, it was ultimately government regulations that caused the trading restrictions they didn’t expect.

What happens when you buy a stock

So, if you buy GameStop, AMC, or some other stock, there is a bunch of activity going on behind the scenes:

1. You submit an order and it executes. (You’ve bought a stock.)

2. At the end of the day, the broker has the money it needs to send to DTCC.

3. Based on the aggregate account for a particular stock, if the broker has to send money on net to DTCC, it will need to borrow that money.

Since it’s a short-term transaction, the borrowing is normally done through cheap interbank lending.

If brokers have net proceeds in a particular account, DTCC sends it to those brokers.

4. Settlement of the transaction occurs within two days.

Forms of credit/counterparty risk

As you can see, there are different forms of credit risk associated with the different entities involved.

1. Buying broker and DTCC

If a client executes a trade before the close of business, there’s credit risk between the time the transaction is executed and the end of the day.

2. DTCC and itself

There’s credit risk between the time DTCC sends net proceeds and when it officially settles the transaction.

3. DTCC and selling broker

DTCC owes the selling broker proceeds at the end of the day.

4. Selling client and selling broker

The selling broker uses its credit line to provide its client with the proceeds immediately when the transaction executes

5. Buying client and buying broker

In the case of Robinhood, you make a deposit of a certain amount and a margin account is opened.

As mentioned earlier in the article, traders on Robinhood are primarily the product.

Its customers are mainly market makers who buy the order flow and monetize that soon-to-be-executed trade activity by feeding that information into their algorithms.

Very small amounts are made by the market maker on each trade by slightly reducing the quality of the execution. This enables it to be free without paying any commission.

In this case, buying a stock on Robinhood doesn’t mean you technically own it. It simply passes through the rights.

If Robinhood were to fail, you would not own the stocks in your account. You would have a claim against Robinhood as a creditor up to a certain amount of insurance protection (depending on the mix of cash and securities).

This is all spelled out in Robinhood’s customer agreement and terms of service. It’s necessary to agree to this before signing up.

Robinhood’s variable-rate lending

On top of that, Robinhood also has the ability to take the stock that you buy and lend it out to others to short.

Robinhood makes a variable rate on this stock loan depending on supply and demand. If the demand to short a stock is high, the rate is higher if there are fewer shares available.

If something has less demand and more shares available the rate is lower.

Many brokers share the lending proceeds with their clients. But Robinhood doesn’t. It keeps all the proceeds.

In addition to payment for order flow, payments from proceeds on “hard to borrow” stocks can be quite a bit as well.

Something like Apple (AAPL) is easy to borrow and the rates are generally very cheap. In a low-rate environment, it’s almost nothing.

Something like GameStop (GME) can command much higher rates. The rate is reset daily based on the supply/demand dynamics.

When somebody wants to short a stock, the broker needs to first locate them. If they can, the borrow rate is published and the entity shorting (e.g., an individual, hedge fund/institution, whoever) can decide if they want to go through with selling the shares.

The broker lends the shorting client the shares, which the client sells, receiving a cash credit in return.

The client has cash that it can earn interest on potentially – if it has a positive net balance – and owes shares and pays borrowing costs on the paid shares. It may also have to pay dividends on those shares if necessary. Then there are, of course, market-to-market fluctuations in the share price that are a big determinant in the profit/loss of the trade.

Evidence of potential brokerage solvency risks in volatility data

For reasons covered in this article, whenever there’s a large deviation of volatility relative to expectations and in certain pockets of the markets, it can lead to solvency risks for brokers.

This is also true for a select number of long/short hedge funds on the wrong side of the trade(s).

This can be reflected in such measures like VIX (i.e., implied volatility) relative to realized volatility. This was at an all-time high January 27. “Vol of vol” (VVIX index) was also near an all-time high. VVIX measures the volatility of options on the S&P 500 index.

(Source: Bloomberg, Artemis Capital Management)

Conclusion

Market players getting squeezed is nothing new in markets. Traders prey on each other all the time.

What made ‘GameStop mania’ unique was the channel of communication (social media) and the general idea of trying to make markets go “wrong” (unsustainably high) instead of a “right” (a more plausible equilibrium).

But all of this new trade activity and volatility caused some brokers (notably Robinhood) to run into regulatory capital issues due to the lending interactions and counterparty risk that take place between buying clients, buying brokers, selling clients, selling brokers, and DTCC.

Robinhood had to place trading restrictions on some securities (e.g., GME, AMC, EXPR, KOSS) and raise over $3 billion of new capital.

Ultimately, it was government regulations that tripped up speculators in their quest to make money in these markets.