Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) – Can You Own or Trade Them?

What are Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)?

How do you get ahold of them?

Can you trade them?

We cover all of this in this article.

Key Takeaways – Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)

- PGMs are six ultra-rare, chemically related metals, which are primarily used as industrial catalysts, not monetary metals or stores of value.

- Demand is driven by automotive emissions, electronics, and advanced manufacturing, not store-of-value behavior.

- The six PGMs are platinum, palladium, rhodium, iridium, osmium, and ruthenium.

- Most are mined together as byproducts.

- South Africa and Russia dominate global supply. This creates chronic geopolitical and operational risk.

- Platinum and palladium are the only PGMs with meaningful investment access. Others are illiquid and opaque with respect to access and pricing.

- PGM markets are small, thin, and volatile compared with gold and silver.

- Can they evolve into monetary or monetary hedge assets? It’s unlikely due to their intrinsic character as industrial metals.

Overview

Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) are a family of six chemically related metallic elements that sit together in the periodic table and share a distinctive combination of chemical properties.

They are all:

- Dense

- Corrosion-resistant

- Excellent catalysts, and

- Unusually stable at high temperatures

These characteristics make them highly useful in modern industry. Their rarity also constrains supply and drives unique market dynamics.

The six PGMs are:

They’re rarely found in pure form.

They’re also typically mined together from the same ore bodies. Then they’re separated through energy-intensive refining processes.

Production is geographically concentrated. South Africa dominates primary supply, followed by Russia, Zimbabwe, and smaller contributors such as Canada and the United States.

Let’s go through them one by one.

Shared Characteristics

All PGMs show:

- high melting points

- chemical stability, and

- catalytic efficiency

They’re geographically concentrated in supply and capital-intensive to refine.

These traits create recurring supply shocks and long investment cycles.

Key Differences

Despite chemical similarities, each PGM is distinct in its own way.

Platinum and palladium are semi-investable and heavily tied to the auto sector.

They have very little demand as stores of value or contra-currencies despite their “what about this” kind of interest in a world starved of alternative stores of value.

That market is heavily focused on gold and, to a lesser extent, silver.

Rhodium, iridium, and ruthenium are industrially essential but financially illiquid.

Osmium remains largely peripheral, as there’s so little of it in the world and so little mined.

Strategic Importance

PGMs are used in environmental regulation and advanced manufacturing, and geopolitical risk affects how much each country can get.

They’re critical to emissions control, electronics, and emerging hydrogen technologies, so there’s long-term industrial relevance even as demand patterns evolve over time (e.g., electric vehicles, environmental regulations, advances in materials science).

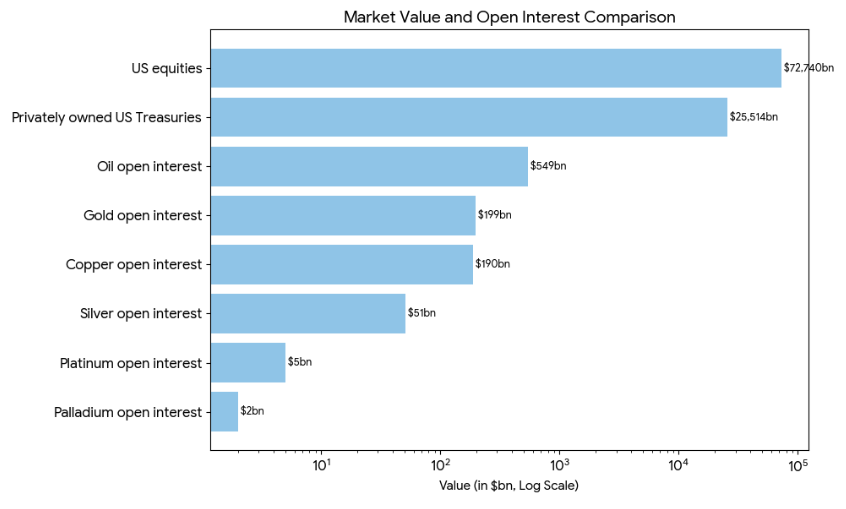

Relative Market Size

These markets are small. By comparison, these are the relative sizes of the platinum and palladium markets compared to equities, Treasuries, and other markets (as of year-end 2024):

- US equities: $72,740 billion (approx $72.7 trillion)

- Privately owned US Treasuries: $25,514 billion (approx $25.5 trillion)

- Oil open interest: $549 billion

- Gold open interest: $199 billion

- Copper open interest: $190 billion

- Silver open interest: $51 billion

- Platinum open interest: $5 billion

- Palladium open interest: $2 billion

(Data source: USGS, Goldman Sachs, graph by author)

Platinum (Pt)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Platinum is naturally the most popular of the six.

It’s a dense, silvery-white metal with exceptional resistance to corrosion and oxidation.

It remains chemically stable at high temperatures and doesn’t tarnish in air.

These properties mean that platinum can function reliably in extreme industrial environments where many other metals fail.

(For example, standard industrial metals like iron, copper, aluminum, nickel, zinc, and lead will at a point run into issues with melting, deformation, oxidation, or corrosion.)

Industrial Applications

Platinum’s largest end use is in catalytic converters for gasoline vehicles.

In these contraptions, platinum helps convert carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides into less harmful emissions to reduce air pollution.

It’s also critical in things like chemical processing, petroleum refining, glass manufacturing, and hydrogen production.

There are also electronics applications. Hard disk, thermocouples, and specialized sensors are examples.

Jewelry and Investment Demand

Platinum has long held a place in high-end jewelry due to its durability, purity, and prestige. Platinum often, but not always (due to its industrial cyclicality), trades at a premium to gold.

Investment demand exists through bars, coins, and physically backed funds.

ETFs like PPLT and PLTM are available and can be traded daily.

At the same time, the platinum market is structurally smaller and more cyclical than gold.

Platinum trades more like an industrial metal than a monetary asset, which reduces its structural appeal. Pricing is sensitive to auto demand and substitution trends.

Market Dynamics

Platinum supply is highly exposed to labor disruptions, energy shortages, and political risk in South Africa.

On the demand side, substitution between platinum and palladium in catalytic converters is influential in price cycles.

Platinum is liquid relative to other PGMs. But it’s still thin compared with gold or silver.

In terms of demand:

Platinum is ~5-7% of gold’s annual market.

It’s ~15-20% of silver’s annual market.

In terms of scarcity, which we can measure in above-ground stock:

Platinum vs. Gold: ~1-2%

Platinum vs. Silver: ~5-7%

What we can glean from this is that platinum is far scarcer physically than gold or silver. But it’s far less liquid financially.

Gold and silver markets are made up large, stable above-ground inventories and come with massive monetary demand.

Platinum trades on a much smaller, thinner industrial flow.

As such, this is why we see platinum experience sharp price moves despite low overall market depth.

Where it’s Mined

South Africa dominates here:

- South Africa: ~70-75%

- Russia: ~10-12%

- Zimbabwe: ~7-8%

- Canada: ~4-5%

- United States: ~2-3%

- Other countries: ~3-5%

Palladium (Pd)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Palladium is lighter than platinum and has strong catalytic activity, especially for oxidation reactions.

It absorbs hydrogen efficiently.

This makes it widely useful in purification systems as well as certain chemical processes.

Industrial Applications

Palladium is simlar to platinum in that it’s primarily used in catalytic converters for gas vehicles.

It became dominant during the 2000s due to cost advantages over platinum.

You also see it in electronics, dentistry, chemical catalysts, and hydrogen-related technologies.

Market Structure and Volatility

Palladium markets are structurally tight.

Above-ground inventories are limited. Mine supply is heavily concentrated in Russia and South Africa.

This combination means that historical price action has seen sharp price spikes during supply disruptions. Regulatory shifts in auto emissions standards are another driver.

Investment Characteristics

Palladium is investable through bars, coins, and exchange-traded products (PALL, an ETF with an expense ratio of around 0.60%).

But liquidity is thinner than platinum.

Prices tend to be extremely volatile, driven by auto sector demand and substitution dynamics.

Macroeconomic hedging behavior doesn’t have a big role, so there is generally minimal strategic demand from macro hedge funds and other types of market players looking for alternative stores of value.

Where It’s Mined

- Russia: ~40-45%

- South Africa: ~35-40%

- Canada: ~5-7%

- United States: ~4-5%

- Zimbabwe: ~3-4%

- Other countries: ~3-5%

Rhodium (Rh)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Rhodium is one of the rarest and most reflective metals on Earth.

It has exceptional resistance to corrosion and high melting temperature.

It’s especially prized for its unmatched catalytic efficiency for reducing nitrogen oxides.

Industrial Applications

Rhodium, like platinum and palladium, is almost exclusively used in automotive catalytic converters (emissions control in gasoline engines).

Small quantities have an outsized impact on performance.

So even minor supply disruptions can cause dramatic price movements.

Supply Constraints

Rhodium isn’t mined independently.

It’s a byproduct of platinum and palladium mining.

Accordingly, supply can’t easily respond to price increases.

Because of the structural rigidity in its market, this makes rhodium the most volatile of all PGMs.

Market and Investability

There’s no deep futures market for rhodium.

Trading is largely over-the-counter. Prices can be opaque and it’s illiquid.

Investment access is heavily limited to physical bars and specialized products.

There are physically backed products like the Xtrackers Physical Rhodium ETC (XRH0) (listed in London) or the 1nvest Rhodium ETF (ETFRHO) (South Africa), but no US-based products.

This makes rhodium unsuitable for most institutional portfolios despite its price cycles occasionally making it into the financial news.

Where It’s Mined

- South Africa: ~80-85%

- Russia: ~8-10%

- Zimbabwe: ~3-5%

- Canada: ~1-2%

- Other countries: ~2-4%

Iridium (Ir)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Iridium is extremely dense and one of the most corrosion-resistant elements known.

It maintains its structural integrity under extreme heat and pressure, including conditions that would otherwise destroy most metals.

Industrial Applications

Iridium is used in spark plugs, crucibles, chemical catalysts, medical devices, and aerospace components.

Essentially the applications are specialized coatings and certain electronics where durability is front and center and can’t be compromised.

Rarity and Supply

Iridium is among the scarcest elements in the Earth’s crust.

Annual global production is tiny. Approximately 6-9 metric tonnes are mined per year (≈6,000 kg to 9,000 kg).

Like rhodium, it’s recovered only as a byproduct of other PGMs.

In iridium’s case, it’s heavily a product of platinum and nickel mining, rather than a primary mined metal.

This scarcity leads to chronic supply inflexibility.

Market Characteristics

Iridium pricing is opaque and largely contract-based.

There’s almost no speculative investment demand. Liquidity is minimal.

Price behavior is driven by industrial supply-demand imbalances rather than macroeconomic trends.

Essentially nobody uses iridium in a gold-like, monetary hedge type of way.

Where It’s Mined

- South Africa: ~75-80%

- Russia: ~10-12%

- Zimbabwe: ~5-7%

- Canada: ~2-3%

- Other countries: ~2-4%

Osmium (Os)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Osmium is the densest naturally occurring element (element 76 on the periodic table)

It has a bluish-silver appearance and a very high melting point.

In powdered or oxidized form, it can be toxic. So this limits its practical handling.

Industrial Applications

Osmium has very limited industrial use.

It’s mainly used in specialized alloys, electrical contacts, fountain pen tips, and niche scientific applications.

Its role in modern industry is marginal compared with the other PGMs we cover here in this article.

Market Reality

For any prospective osmium investors or traders out there, the unfortunate reality is that there’s no meaningful global osmium market.

Production volumes are extremely small. We’re talking approximately 0.5-2 metric tonnes per year (≈500-2,000 kg), though production estimates therefore vary by year and are inherently imprecise.

As such, that makes osmium the least-produced platinum group metal.

It’s recovered only in trace amounts as a byproduct of platinum and nickel refining.

Moreover, most osmium is not traded through standardized channels – i.e., not into open, standardized global market.

There have been recent attempts to market crystalline osmium as a collectible asset. But this is more novelty than fundamental demand.

Investment Assessment

Osmium lacks liquidity, transparency, and industrial scalability. From a financial perspective, it functions more like a collectible than an investable metal.

We have no idea what its price would be. Supposedly, it traded for around $2,900 in early 2024 for a 1 troy ounce pellet (31.1 grams).

But for higher purity (>99.95%), it would likely be in the five figures per ounce.

There are only a small subset of people who might have inside information on osmium prices, and I’m unfortunately not one of them.

Where It’s Mined

- South Africa: ~70-75%

- Russia: ~10-15%

- Zimbabwe: ~5-8%

- Canada: ~2-3%

- Other countries: ~2-5%

Ruthenium (Ru)

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Ruthenium is a hard, brittle metal. It’s known for its strong catalytic properties and good resistance to wear.

It improves hardness and corrosion resistance when alloyed with other metals.

Industrial Applications

Ruthenium is widely used in electronics – e.g., chip resistors and data storage technologies.

It also serves as a chemical catalyst and is used in certain solar cells and electrochemical applications.

Supply and Demand Profile

Like other minor PGMs, ruthenium is produced only as a byproduct.

Demand is tightly linked to electronics manufacturing cycles rather than automotive emissions.

This gives it a distinct demand profile within the PGM complex.

Market Characteristics

Pricing is opaque. Volumes are thin. There’s virtually no retail investment market.

Ruthenium is best understood as a strategic industrial input rather than a financial asset.

Where It’s Mined

- South Africa: ~75-80%

- Russia: ~10-15%

- Zimbabwe: ~5-7%

- Canada: ~2-3%

- Other countries: ~2-5%

Why Are Gold and Silver Not PGM?

Gold and silver are often discussed alongside platinum and palladium because all four are precious metals.

Nonetheless, gold and silver are not classified as Platinum Group Metals because the PGM designation is a chemical and crystallographic classification, not a value-based or historical one.

1. Periodic Table Position and Electron Structure

Platinum Group Metals occupy Group 10 and Group 8-9 transition metal blocks of the periodic table and share similar d-orbital electron configurations.

These shared electronic structures explain their common catalytic behavior, high melting points, and chemical stability under unconventional/extreme conditions.

Gold and silver sit in Group 11 (the coinage metals).

Their outer electron configurations differ materially, which leads to very different chemical behavior.

This is the primary scientific reason gold and silver are excluded from the PGM family.

2. Chemical Reactivity and Catalytic Behavior

PGMs are very good heterogeneous catalysts.

Their surfaces accelerate chemical reactions without being consumed, even at high temperatures and in corrosive environments.

This catalytic property is the defining feature of PGMs as a group.

Gold and silver don’t show the same catalytic profile:

- Gold is chemically inert and historically prized – for literally thousands of years – for resistance to oxidation.

- Silver is more reactive than gold but oxidizes and tarnishes readily.

Gold can act as a catalyst at the nanoscale and silver has antimicrobial and conductive uses, but these behaviors don’t align with the industrial catalytic role that unifies PGMs.

3. Geological Formation and Ore Associations

Platinum Group Metals are typically found together in the same ore bodies – especially in layered mafic and ultramafic igneous formations.

South Africa is so rich in platinum group metals because it hosts these vast intrusions.

This is most notable in the Bushveld Complex, which covers 66,000 km^2. Here, slow-cooling magma from a geological event 2.05 billion years ago concentrated PGMs into laterally extensive, mineable layers.

They form through these similar geochemical processes and are mined as a group, then separated during refining.

Gold and silver form in entirely different geological environments, including hydrothermal veins and sedimentary deposits.

They’re often mined independently. And they don’t co-occur with PGMs in economically meaningful concentrations.

4. Physical Properties and Density

PGMs are among the densest elements on Earth and are known for their very high melting points.

This makes them suitable for extreme industrial environments.

Gold and silver have:

- Lower melting points

- Lower densities

- Higher malleability

These physical differences reinforce their separation from PGMs in both science and industrial practice.

5. Historical and Economic Classification

Gold and silver earned their status as precious metals primarily through monetary history.

They served as money, reserves, and stores of value for thousands of years.

PGMs, by contrast, gained importance through modern industrial chemistry and emissions control, not monetary systems.

Even today, PGMs trade primarily as industrial commodities rather than monetary hedges.

Summary

In short, gold and silver are not Platinum Group Metals because:

- They don’t share the same electron structure

- They lack the defining catalytic chemistry

- They form in different geological settings

- They have distinct physical properties

- Their economic role is monetary rather than catalytic

The PGM label is therefore a scientific classification, not a judgment of rarity, value, or prestige.

Where Gold and Silver Are Mined

Gold:

- China: ~10-12%

- Australia: ~9-10%

- Russia: ~9-10%

- Canada: ~6-7%

- United States: ~5-6%

- Other countries: ~50-55%

Silver:

- Mexico: ~23-25%

- China: ~13-15%

- Peru: ~11-12%

- Chile: ~5-6%

- Australia: ~5-6%

- Other countries: ~35-40%

Top Mining Companies for Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)

So, we’ve established that outside platinum, and maybe palladium, it’s very hard to get investment access to PGMs.

But is it possible to get access to the miners that produce them?

We have the following lists below between majors, diversified miners, and North American specialists:

Major Primary PGM Producers

- Anglo American Platinum – World’s largest primary PGM producer. Dominant exposure to platinum (38% of world’s supply), palladium, rhodium. It trades on the OTC markets as Valterra Platinum Limited (OTCMKTS: ANGPY). (Anglo American Holdings Ltd. is the parent company.)

- Impala Platinum – Large diversified PGM output. Has significant rhodium and palladium byproducts. OTC (ADR): IMPUY

- Sibanye-Stillwater – Major global PGM producer. Has operations in South Africa and the United States. NYSE: SBSW

- Northam Platinum – Mid-tier PGM producer. High exposure to platinum and rhodium. OTC: NHMJF

You can also get more direct access to these on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

Integrated / Diversified Miners with Large PGM Output

- Norilsk Nickel – World’s largest palladium producer. PGMs primarily from nickel-copper operations. Moscow Exchange: GMKN; (Limited Western access due to sanctions; no active NYSE ADR)

- Glencore – Produces PGMs as byproducts from nickel and copper assets. London Stock Exchange: GLEN; OTC: GLNCY

- Vale – Palladium and platinum produced as byproducts of nickel mining. NYSE: VALE

North American PGM Specialists

- Stillwater Mining Company – Historically the only primary PGM miner in the United States; now part of Sibanye-Stillwater. No longer publicly traded (acquired by Sibanye-Stillwater). Exposure now via: SBSW

- Ivanhoe Mines – Emerging PGM exposure through large-scale polymetallic African projects. Toronto Stock Exchange: IVN; OTC: IVPAF

Key Industry Reality

PGM supply is highly concentrated among a small number of companies.

South African producers dominate platinum and rhodium.

Russian nickel-linked producers dominate palladium.

There are no meaningful “junior-only” PGM markets at scale, like you see with gold, silver, and conventional industrial metals.

Most production comes from large, capital-intensive operators.

Is It Posssible for PGMs to Evolve into Monetary Stores of Value?

In theory, yes. In practice, it is highly unlikely for most PGMs.

What Makes a Monetary Store of Value

To function as a monetary asset, a metal needs:

- Large, stable above-ground inventories

- Deep, liquid, globally trusted markets

- Low industrial dependency

- Price formation driven by macro demand, not supply shocks

- Historical or institutional anchoring (reserves, savings, collateral)

Gold fits this criteria. Silver has to a lesser extent and correlates more with growth assets because of its industrial input.

Why PGMs Struggle Structurally

- Industrial dominance – PGMs derive most demand from emissions control, electronics, and chemicals, not savings behavior.

- Thin markets – Volumes are too small for reserve-scale allocation without extreme volatility.

- Supply rigidity – All PGMs are byproducts; supply cannot expand to meet monetary demand.

- Price instability – Rhodium, iridium, ruthenium, and osmium exhibit order-of-magnitude swings, disqualifying them as stores of value.

- No monetary history – Unlike gold and silver, PGMs lack centuries of trust, reserve use, and legal tender legacy.

The Only Partial Exception: Platinum

Platinum comes closest due to:

- Physical durability and scarcity

- Some investment products (bars, coins, ETFs)

- Historical periods trading above gold

However, platinum still behaves like an industrial cyclical asset, not a monetary hedge.

Its price is driven by auto demand and substitution, not currency debasement.

Why Palladium and Others Fail the Test

- Palladium – Too volatile, auto-sector dependent.

- Rhodium and Iridium – Illiquid, opaque, no scalable markets.

- Osmium and Ruthenium – Niche industrial or collectible status only.

Overall

In an environment with rising government deficits, political risk, geopolitical fragmentation, and a lack of good money alternatives, there’s a big demand for a wider range of stores of value.

At the same time, it’s a matter of intrinsic reality.

PGMs are strategic industrial metals, not monetary metals.

Even under currency debasement or commodity re-monetization scenarios, gold will remain structurally dominant, silver secondary, and PGMs peripheral.

PGMs may hedge supply shocks. They don’t inherently hedge money.

Conclusion

Platinum Group Metals form a small – but strategically important – corner of the global metals complex.

Their extreme rarity, industrial indispensability, and concentrated supply chains create unique economic and market behaviors.

Understanding the full PGM suite requires treating each metal individually rather than as a monolithic group.

Platinum and palladium attract most attention, but the lesser-known PGMs are important for modern technology in ways that are disproportionate to their visibility or market size.