Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Basics: Accretion/Dilution Model

An accretion/dilution analysis helps to determine the cost-effectiveness of a potential merger and acquisition (often termed M&A) deal.

Mergers and acquisitions are made with the intention of improving the financial performance of each firm relative to what they could accomplish independently. This can be achieved by firms’ ability to reduce costs, combine talent and/or technology, or eliminate competitors.

This allows for greater efficiency and ideally improves economies of scale such that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

The fundamental goal of an accretion/dilution model is to assess the impact of a potential acquisition of a target company on the acquirer’s earnings per share (EPS). All accretion/dilution modeling essentially reduces down to earnings per share analysis.

Accretive or Dilutive?

A deal is considered accretive if it will have the effect of increasing the acquirer’s EPS. (The acquirer’s potential EPS is regularly termed pro forma EPS, meaning EPS projected in advance of a business deal.)

A deal is considered dilutive if it will have the effect of decreasing the acquirer’s EPS, which is generally frowned upon, especially so if it lasts long-term.

A deal that will have no effect is considered breakeven.

All deals are fundamentally about adding value in excess of the costs.

Framework of the Accretion/Dilution Model

The spreadsheet we will be using is slightly modified from a version used by Wall Street Prep (linked here). There are various templates available, but we chose this one for its simplicity.

It highlights the main function of the model without going overboard on the details we would need if examining two actual companies.

Despite that, this spreadsheet outlines a rudimentary means to perform accretion/dilution such that we see how a mergers and acquisitions deal actually works in terms of the basic inputs in play.

Inputs

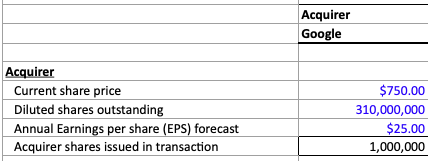

For the acquirer, we need the following inputs:

- Current share price

- P/E ratio

- Diluted shares outstanding

- Acquirer shares issued in the transaction

The current share price divided by price/earnings (P/E) ratio will give us EPS forecast for the next year.

This will be the benchmark on which the effectiveness of the deal will be compared to. If pro forma EPS is higher than the EPS derived from these inputs, the deal will be considered accretive. If lower, then will be dilutive.

Diluted shares outstanding references the number of shares that would be outstanding if all sources of conversion, such as convertible bonds and stock options available to employees, were exercised. Undiluted merely refers to all common shares of stock available.

For purposes of deriving implied standalone net income, we need all types of convertible shares, which are captured via diluted shares outstanding.

We also need a fourth piece of information regarding the prospective acquirer, which is shares that the acquirer would issue as part of the transaction.

This is calculated by:

Shares issued in transaction = (% of the deal financed through stock) * (Acquirer’s offer value ($) to target) / (Current share price of the acquirer)

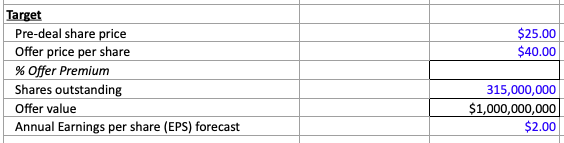

For the target (i.e., the company being acquired), we need the following inputs:

- Pre-deal share price

- P/E ratio

- Offer price per share

- % Offer premium

- Shares outstanding

- Offer value

The % offer premium is how much extra the acquirer is offering to pay to acquire the target. For instance, it makes little sense for the target to accept an offer that is roughly equal to their current value of equity. It must be higher to a degree to incentivize the target company to accept the transaction.

The % offer premium is how much extra the acquirer is offering to pay to acquire the target. For instance, it makes little sense for the target to accept an offer that is roughly equal to their current value of equity. It must be higher to a degree to incentivize the target company to accept the transaction.

We calculate the offer premium by taking Offer price per share and dividing it by Pre-deal share price, and then subtracting one to obtain a percentage:

(Offer price per share) / (Pre-deal share price) – 1

The offer value in monetary terms is equal to:

Offer value = (Offer price per share) * (Shares outstanding)

Assumptions

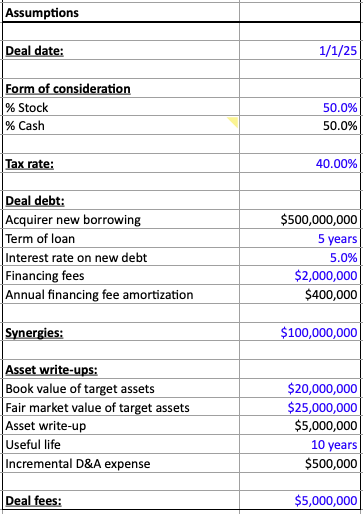

In order to perform this accretion/dilution analysis, we need to input values regarding the framework of the deal itself:

- Deal date (as a matter of answering when the proposed deal is planned for)

- % of the deal financed by stock

- % of the deal financed by cash (assumed to be new debt for simplicity)

- Tax rate

- New borrowing expenses

- Length of the loan

- Interest rate of the loan

- Financing fee of the loan

- Annual financing fee amortization

Synergies

- Book value of target company’s assets

- Fair market value of target company’s assets

- Asset write-up

- Useful life

- Incremental depreciation and amortization (D&A) expenses

- Deal fees

Four of these values are derived via simple calculation (five if you consider percent of the deal financed by cash is (1 – % stock)).

Four of these values are derived via simple calculation (five if you consider percent of the deal financed by cash is (1 – % stock)).

Acquirer new borrowing (cash needed) is determined by offer value multiplied by the percentage of the deal that will be financed via cash.

Annual financing fee amortization is financing fees divided by the length of the loan.

The asset write-up is (Fair market value of target company’s assets) – (Book value of target assets).

Incremental D&A expense is equal to asset write-up divided by the useful life (in years) of the assets.

If the useful life is determined to be ten years, for example, then the assets will incur a loss of value equal to the fair market value of the target company’s assets minus the book value of target assets, with that figure divided by ten.

Deal fees are simply the advisory costs involved in a merger and acquisition deal.

Analysis

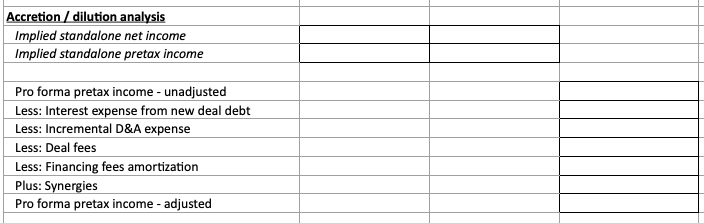

In order to determine our eventual outputs informing us whether a merger/acquisition deal is accretive or dilutive, we need to form additional financial information from our inputs.

We need the following from both the acquirer and target: implied standalone income and implied standalone pretax income.

Implied standalone income is the company’s upcoming year EPS forecast multiplied by diluted shares outstanding (for the acquirer, simply shares outstanding for the target).

Implied standalone pretax income takes that value but with taxes taken out – Implied standalone net income / (1 – Tax rate).

Now we can actually begin to form a financial understanding of these two companies if they existed as one (Company A acquiring Company B).

To do this, we need to find Pro forma pretax income (adjusted).

We can do this via the following formula:

Adjusted pro forma pretax income= Implied standalone pretax income | acquirer + Implied standalone pretax income | target – Financing fees * Length of loan – Incremental D&A expense – Deal fees – Financing fees amortization + Synergies

To find Pro forma net income, we take the value just derived and take the taxes out:

Pro forma net income = Adjusted pro forma pretax income / (1 – Tax rate)

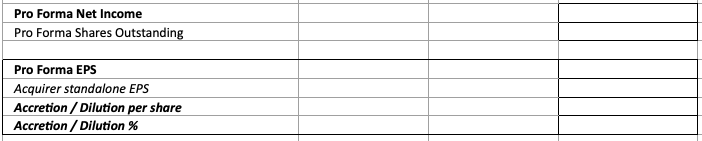

The pro forma shares outstanding is equal to the diluted shares outstanding of the acquirer minus the number of shares the acquirer will issue in the transaction. It comes in the form of a blank table.

Outputs

Our final output to the model is pro forma EPS, or the projected earnings per share for the acquirer should they acquire the target. This was we can understand if the acquirer will gain from the deal (accretive), lose from the deal (dilutive), or simply breakeven with no financial impact. We do this by dividing our pro forma net income by the number of pro forma shares outstanding.

We can find the accretion or dilution per share in the potential deal by subtracting the acquirer’s standalone EPS from the pro forma EPS. That is, how much has the acquiring accreted or diluted on a per share basis. If the deal is accretive, this will yield a positive value. If the deal is dilutive, it will give a negative value.

We can also read the projected level of accretion or dilution by deriving an accretion/dilution percentage. This is simply:

Acquirer standalone EPS / Pro forma EPS – 1

What Impacts Accretion/Dilution Value

Given our inputs, there are certain variables that tend to affect the accretion/dilution percentage most.

The prominent two with respect to the target are its upcoming year EPS forecast and shares outstanding. If the EPS forecast decreases relative to some starting point, the value of accretion (assuming the deal was accretive in the first place) will decrease.

If the number of shares outstanding decrease, then the value of accretion will decrease as well.

The level of synergy in the deal can have a marked effect on EPS. The level of synergy created in the deal is largely the purpose for making it in the first place.

If the firms did not operate more efficiently or achieve greater financial results together than they do apart, there would be little use to considering the acquisition/merger.

For a pro forma EPS of $200 million, a $10 million change in synergy will generate an EPS variation of perhaps around $0.25 per share, which is a reasonably large change.

How do we evaluate synergy? For the simplicity of this spreadsheet, it’s simply written in as an input.

In actuality, there is an entirely different financial model for this. Or at least a portion of one that is determined by several additional inputs.

The pre-deal share price of the target company has zero effect on the value of accretion.

It is totally predicated on the offer share price, as that is what financially effects the accretive value, as the target company being absorbed into the acquirer makes its current share price irrelevant on its own.

Variables that have a slight to moderate effect on the value of accretion include:

- Offer share per price

- Financing fees

- Tax rate

- Asset write-up

- Useful life

- % Stock or % Cash used in the deal

Although the pre-deal share price of the target has no effect, the offer share price doesn’t have a significant effect either. The offer price per share has an inverse relationship to the accretive value. If the offer price per share decreases, the value of accretion increases.

This is simply due to the fact that if the acquirer pays less money to buy the target, the acquirer saves money (income) and hence increases its EPS.

The lower the financing fees, the higher the accretive value (another case of saving money). But the effect is not strong. A couple million saved in financing fees between two moderately sized firms will boost EPS by perhaps $0.01.

The lower the tax rate, the higher the pro forma EPS. This is also readily intuitively understandable based on the fact that the acquirer is saving money with the lower tax rate.

At a $200 million pro forma net income, a 5 percent drop in the tax rate could boost pro forma EPS by approximately $0.15.

The smaller the asset write-up (i.e., discrepancy between fair market value of target assets and book value of target assets), the higher the pro forma EPS.

But like the aforementioned two, the difference will typically be a couple cents per share if we are talking about a difference of $10 million in a deal that forms a pro forma net income of only about $200 million.

The greater the useful life of the assets (i.e., smaller depreciation and amortization rate), the higher the pro forma EPS.

The percentage of stock or percentage of cash used in a deal can alter pro forma EPS a moderate amount of negligibly depending on the extent.

If we are in a deal that’s under a 50/50 stock-to-cash financing consideration and this shifts to 60/40 at a $200 million pro forma net income, we might be looking at a +$0.05-$0.06 change in pro forma EPS.

However, let’s say we go from all stock to all cash, or from all cash to all stock.

At the same $200 million pro forma net income, it could be around a +$0.70 change in EPS. The greater the amount of cash used in the deal’s financing, the higher the resultant accretion in EPS.

Additional Items

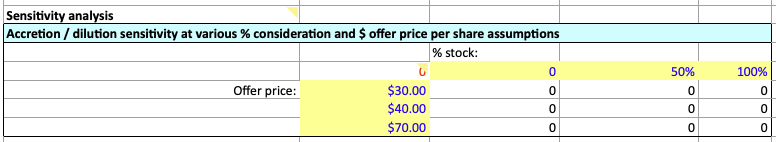

At the bottom of the spreadsheet is a sensitivity analysis table. This is designed to compare sensitivity in the accretion/dilution per share based on both offer price and percent of stock used to pay for the deal.

There are three stock financing percentages – 0 percent, 50 percent, and 100 percent. And three offer price deals.

Conclusion

In sum, the central purpose of an accretion/dilution model is to assess the impact of a potential mergers and acquisitions deal on the acquirer’s earnings per share (EPS).

This degree of accretion/dilution is impacted most prominently by P/E ratio, offer price per share, the financing form (stock/cash ratio), and the level of synergy in a projected deal.

A deal will always be accretive when the acquirer’s P/E ratio is higher than that of the target. If a deal involves 100 percent stock financing (no cash), a higher P/E for the acquirer will prevent it from needing to offer more than a 1:1 ratio of its own shares for the target company’s shares.

For example, if the acquirer has a P/E ratio of 10 and the target has a P/E ratio of 20, the acquirer will need to issue two shares in order to acquire just one share of the target.

The non-benefit of share dilution in that case will more than offset any increase in net income. This doesn’t mean that the deal cannot be accretive. It can be if the monetary value of synergy is sufficiently high, then the deal can still be breakeven or accretive.

For instance, going back to our $200 million pro forma net income deal, for an acquirer with a P/E of 10 and a target with a P/E of 20, synergy would need to be approximately $27 million, or 13.5 percent of the pro forma net income.

At smaller level deals, synergy would need to be closer to 20 percent of pro forma net income.

In the end, an acquisition deal can create shareholder value by buying a target company with an intrinsic value that is less than the purchase price.

So if the acquirer purchases the target for a 50 percent premium, the acquirer must be certain that the intrinsic value of the company plus the underlying synergy in the deal provides greater than a 50 percent value in order to add to shareholder value.

Even though discussion of this model can be somewhat involved, this is still a much simplified accretion/dilution analysis versus an entire Excel workbook that would actually be used in an actual analysis of a potential merger and acquisition deal.

However, it covers all the basics to learn how the accretion/dilution model works as a whole and fundamentally boils the model down to where it truly lies, which is earnings per share analysis.