Will We Have a Recession Within 18 Months?

Due to the stream of recent events, there’s been discussion on whether a recession is likely in the US and other developed market economies within the next 1-2 years.

For example, over the past few months, we’ve seen the following:

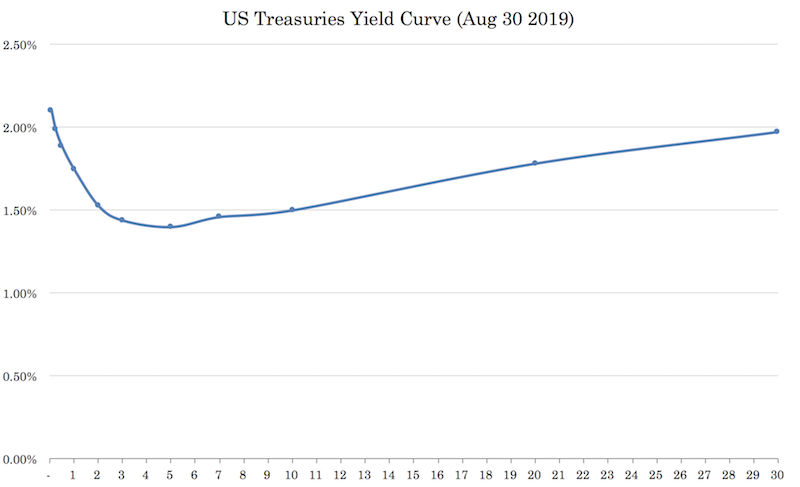

1. Various yield curve inversions in various developed market economies

2. Slowing growth

3. Tepid inflation

4. Easing central banks, or messaging of an intent to ease

5. The rush into safe haven assets, such as US Treasuries, German bunds, gold, yen, and the Swiss franc

6. Worsening of US-China trade relations, and evidence of a broader geopolitical competition and disagreements with respect to currency management, intellectual property, forced technology transfer, government subsidies, market access, market competition, global spheres of influence, cyber-espionage, and related sub-categories.

Will we have a recession?

It largely depends on what policymakers do and the range of unknowns is much larger than the range of knowns. Broadly speaking, nominal interest rates need to remain below nominal growth rates otherwise debt servicing payments will eventually swamp the ability to pay them and growth will contract. This is a basic matter of financial and economic sustainability.

If the Fed follows nominal growth down (cutting 100bps over the next 9-12 months), the economy should be fine. They’re in a difficult situation currently with the overnight rate higher than anywhere else on the curve. Investors currently earn higher interest on money they lend overnight than they do on a 30-year bond by some 0.2 percent.

Given the duration risk associated with a 30-year bond and the fact that you can be sure that that your money will be safer lending it out on merely an “overnight” basis than over the course of 30 years, having cash rates above long-run interest rates doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. It also throws certain business models that rely on the “borrow short to lend long” model for a loop, such as lending institutions (i.e., a large component of the banking system) and many mortgage real estate investment trusts.

For the Federal Reserve, it’s a problem with their mandate with the intense focus on labor conditions, which is a lagging indicator of economic health.

Accordingly, it’s no surprise that they’re regularly behind markets – or more hawkish (i.e., expect rates to remain higher for longer) than markets. That’s why shorting fed funds in the lead up to Fed meetings – or expecting rates to be higher than the market has priced in by a certain date – has been such a strong trade going back to last year. (For the September meeting, the market is roughly in line with expectations).

The longer duration parts of the curve, which are controlled by traders and the broader free market, on the other hand, have gone down materially.

10-year US Treasuries peaked at around 3.2% and are now challenging the all-time low of 1.34% set previously in July 2016.

A third mandate, outside maximum employment and price stability, should come in the form of maintaining sustainable credit growth conditions.

In reserve currency countries, recessions are typically triggered by a contraction in private sector credit creation. As mentioned, debt servicing payments rise in excess of income growth and output necessarily diminishes in conjunction.

While central banks have made strides in better integrating “financial conditions” as a new de facto mandate since the global crisis, there needs to be an increased focus on prudent underwriting standards and other risk mitigation initiatives such as central clearing such that a problem in one sector of the economy should be better contained and less likely to have knock-on effects in others.

However, we are in an environment where economic growth will remain sluggish going forward. There is only so much economies can squeeze out of a debt cycle and most developed markets are approaching the upper limits of those constraints. We know this because rates throughout the developed world are negative, zero, or very close to zero.

When rates are close to zero, it becomes increasingly difficult to push investors out of cash and into riskier assets and to push rates lower in order to increase lending demand and credit creation.

The global economy, especially in developed markets, also faces a longer-term trend of steady demographic headwinds (i.e., aging populations, rising dependency ratios), weaker productivity growth, and intense international competition.

In the last cycle, it was the residential mortgage market and the buildup of underwater loans that hit consumers and caused collateral damage in lending and spending patterns throughout the economy. This cycle it’s in the corporate and government debt markets.

Trade conflicts

China is a rising power gaining strength to challenge the US economically and militarily in much the same way Japan and Germany rose up to challenge the British Empire and allied countries that won World War I.

These types of conflicts are always practically inevitable when one emerging power gains comparable or near-comparable strength (e.g., economically, militarily, technologically) to an existing power.

These tensions inevitably impact trade flows, capital flows, and supply chains, and the China-US situation is playing a significant role in the movement of markets, interest rates, and asset prices. While some market participants view the trade tensions as nothing more than a Trump induced phenomenon, the situation will be with us for many more years irrespective of the US leadership scenario.

The election of somebody different in 2020 or 2024 (either Democrat or Republican) might initially be beneficial for risk assets like stocks and negative for safe haven assets (e.g., US Treasuries, gold, JPY, CHF, German bunds) when taking into account the discounted pricing of the trade tensions. However, these conflicts are driven fundamentally by competing interests in a competitive world.

In the past sixteen times that this type of conflict has played out over the past five centuries, in twelve of those times, a military conflict has transpired to help establish which power is dominant.

The incumbent power typically wants to fight early because it perceives its strength is waning in relative terms. The rising power typically wants to fight later because its strength is gaining but not yet on comparable terms.

This doesn’t mean that the US and China situation will devolve from a “trade war” or “currency war” / “capital war” into something that’s militaristic in some form. But the relationship between the two nations and how that’s handled over the coming years will be very important. Clearly the relationship has gone from each side trying to gain from the other in a mutual way and turned more antagonistic and confrontational.

Of course, from Trump’s point of view, the relationship is too heavily slanted in favor of China. He also tends to view bilateral trade balances as indicative of the direction and magnitude of the “give and take” relationship.

(In the long-run, the influence of tariffs on trade balances is offset by currency moves, with deficit countries seeing a depreciating currency in relative terms and surplus countries appreciating.)

China hawks in the Trump administration largely favor a position of decoupling ties in various respects, as it pertains to trade, supply chains, technology (e.g., the Huawei matter), among other matters. They cite China’s mistreatment and exploitation of foreign companies, its militant behavior toward neighboring countries, and Chairman Xi’s desire to squeeze out domestic dissent.

What traders should take away from “US vs. China”

Traders need to know that the US trade situation with China is not like Canada or Mexico where they work through their fairly straightforward differences, sign some agreement, and everything is “back to normal”. Or the assumption that Trump just needs to be out of office.

It’s a long-term geopolitical confrontation that’s one block in a larger picture of a rising power coming up to challenge the status quo of an incumbent global economic and military superpower. When it comes to structural concessions that impedes China’s long-term goals – e.g., intellectual property, non-tariff barriers such as market access for US companies, government subsidies, technology transfer, cyber-related espionage – China simply won’t follow through as the two sides’ interest are very far apart.

This will also have consequences for the polarity of the global order. Namely, we are likely to go from a largely uni-polar global power structure (US being ahead of everyone else in terms of the size of its economy and military by a wide margin) to bi-polar or multi-polar with the rise of China.

The last time this occurred was during the Cold War era between the US and Soviet Union, roughly from post-World War II until 1991 (though the official demise of the Soviet Union had begun earlier with a highly inefficient state-directed economy combined with a crumbling political structure).

As the US-China relationship unfolds, traders can navigate these differences by betting on what’s going to be good and what’s going to be bad in the context of these trade frictions playing out. Or they can diversify their portfolios to be largely immune from them.

For the vast majority of market participants, the latter approach is the better option.