What Is a Stock-Picker’s Market?

The phrase “it’s a stock-picker’s market” means that there’s enough performance dispersion in the market’s components such that it benefits those armed with better information, analysis, or insight on which securities will outperform (or underperform).

The phrase is typically promoted by active managers and those paid to pick stocks.

Naturally, it’s a controversial claim/slogan given that alpha generation (returns above a representative benchmark) is a zero-sum game. After expenses and fees, it’s negative-sum.

Key Takeaways – What Is a Stock-Picker’s Market?

- We define stock-picking as the extent to which market conditions make it easier for skilled investors/traders to choose which securities are more or less likely to perform well.

- People tend to underestimate variance in markets. It can take a long time or a lot of trials to see skill shine through.

- Achieving a sustainable edge in stock-picking is similar to professional sports, where only a small number develop the skill to win fairly consistently against other professionals while the vast majority of participants are merely recreational players or professionals pursuing more passive strategies (i.e., indexers) and not looking for that level of competition.

- Nobel Laureate William Sharpe argues that active management is mathematically a negative-sum game after fees.

- Fama and French’s research suggests that long-term “star” records are often statistically indistinguishable from luck.

- Consistency is low. S&P data shows zero domestic top-quartile funds maintained that status for five consecutive years.

- Where Alpha Exists – Efficient US large-caps offer little edge, but genuine opportunities exist in niche markets like small-caps, fixed income, and private equity. Information asymmetries allow skilled managers to exploit mispricing.

- Index funds are the better fit for a lot of people in markets, if not most.

- But that’s not to say that active management isn’t right for some.

- Moreover, some traders are genuinely skilled and add clear value to markets.

Basic Performance Data

Nearly 50% of US equity mutual funds beat their benchmark in the first half of 2025 (net of expenses). (Source: SPIVA US Mid-Year 2025 Scorecard (S&P Indices Versus Active))

This represents the best performance for active funds in three years.

The Definition and the “Grain of Truth”

What it Implies

The belief that skilled managers can navigate fraught or unusual markets better than passive indexes.

The Impact of Volatility

Active management tends to perform better relative to benchmarks during volatile periods.

For example, when stock markets are expensive relative to traditional measures – and especially expensive and volatile – this often tends to benefit value and quality over growth and companies with lower-quality assets and more leveraged balance sheets.

When markets are recovering from price declines, on the other hand, this tends to benefit growth over value and riskier securities often outperform.

Examples

The volatility surrounding the tariff-related “Liberation Day” in March 2025.

Skilled traders and investors could outperform in a period by looking at the securities that are more or less impacted by tariffs.

The 2022 bear market (Fed rate hikes by more than discounted into the curve), where nearly half of funds also beat their bogeys.

Managers who were in long-duration names tended to lose a lot in 2022 whereas those who were in more value-oriented names beat the benchmark. (The decline was mostly growth-related; value was only slightly down for the year.)

Variance in Markets vs. Skill

Traders/investors generally underestimate the role of variance in financial markets. They often mistake short-term outcomes for definitive proof of skill.

In reality, asset prices are heavily influenced by random noise (i.e., transactive activity that isn’t relevant to any given edge). This can easily swamp the small edge a skilled manager might possess.

Consequently, a skilled trader or investor can underperform for years due to bad luck, while an unskilled one can ride a lucky streak.

To mathematically separate genuine talent from random chance requires a massive sample size, often decades of data or thousands of distinct bets.

It’s analogous to poker. For a professional vs. a decent amateur or weaker professional, at the sample size of one hand, it’s almost 50/50 (like a single trade or being in markets for a single day). It can take a long time to separate skill levels.

Therefore, evaluating performance over standard one- to three-year horizons is statistically unreliable and often misleading.

How Many Stock Pickers Beat Benchmarks Over Long Time Horizons?

Short-term vs. Long-term

Current success rates are merely a “coin-flip” or slightly worse after factoring in bid-ask spreads and other expenses that come with running a fund (approx. 50%).

The 5-Year Drop-off

S&P data shows only 13% of large-capitalization stock funds beat the market over the past five years.

Investor Psychology

Investors and traders are drawn to active management by the belief in superior individual skill.

Recent good performance by a specific manager drives assets.

The Outlier Effect

Random distribution guarantees some managers will win. This can create the illusion of skill when a lot of it is still variance.

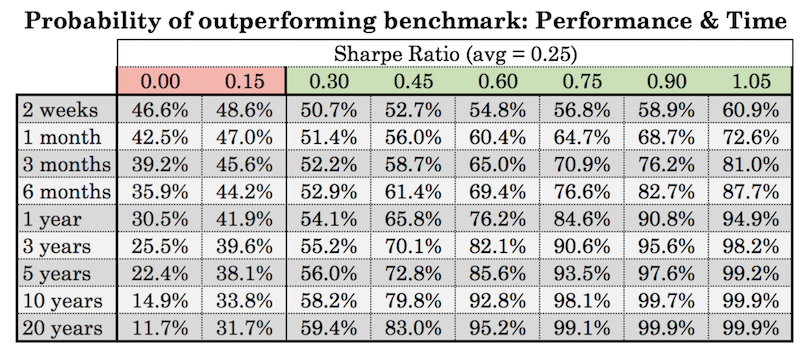

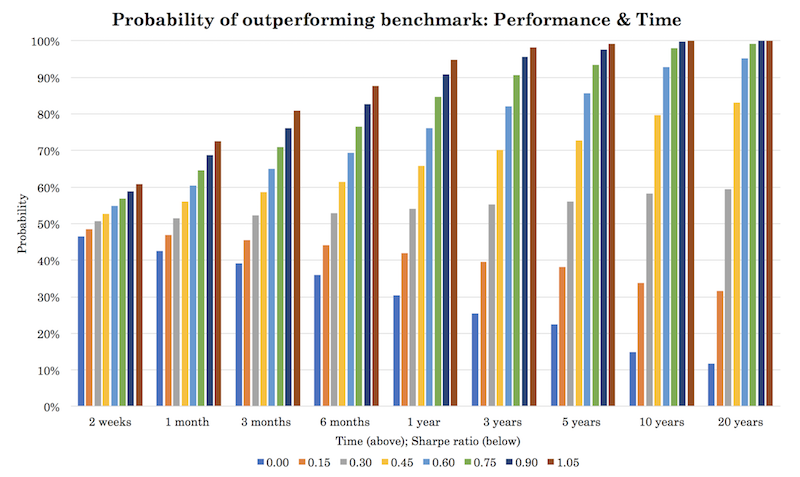

In this article, we looked at skill and the probabilities of seeing it shine through at different time horizons.

Even if a manager adds no value over simply investing in cash (i.e., a Sharpe ratio of 0.0), there’s a 22% chance they could outperform a stock benchmark over 5 years.

And a manager with skill that can outperform with a Sharpe ratio 0.20 above an index still has nearly a 30% chance of underperforming after 5 years.

Exceptions: Where Skill May Exist

Many people are skeptical of stock-picking skill or believe it just doesn’t exist at all.

Famous studies/analogies like “monkeys throwing darts” (and doing just as well, or if not better given the absence of behavioral errors) means a lot of people simply buy index funds and call it a day.

Considering that all known information is already in the price, for most market participants there’s generally not a lot of value to picking stocks for the purpose of beating a standard benchmark. Nor a lot of value in trying to time the market.

At the same time, there is value is having more information or better analysis than the average market participant – even if it is true that it doesn’t apply to the average market participant.

Niche Markets

For large stocks, the bar for proving skill versus luck is extremely high.

It’s more difficult to have unique, profitable insights on stocks when there’s a lot of competition.

The US market, especially among large caps, is among the most difficult markets to add alpha.

For example, am I going to have a unique insight on Google that’s going to allow me to outperform the tens of thousands of other investors in the stock, all of whom are adding some type of information to the price?

The niches we cover below benefit more from human judgment than the large-cap sector.

Other markets, though, can add opportunity.

For example:

1. Value Stocks

Alpha opportunities exist because market sentiment often overreacts to negative news.

Managers profit by identifying fundamentally sound companies temporarily mispriced relative to their intrinsic worth.

2. Small-Cap Stocks

With scant analyst coverage, information inefficiencies are rampant here – if you can figure them out yourself.

Diligent stock pickers can discover high-growth companies and mispriced assets long before institutional investors recognize them.

Small-caps aren’t “easy”; they’re still a hard market to add alpha in. But the competition level isn’t quite like large caps.

3. Fixed Income

The sheer diversity of bonds (e.g., corporate, government, municipal, nominal/inflation-linked) creates pricing discrepancies.

Active managers generate alpha by having unique insights on credit risks, yield curve shifts, and interest rate nuances more effectively than indices.

4. Emerging Markets

Less transparency and lower liquidity create significant information gaps.

For example, not many American or European investors are in China or have a grasp of its unique system, its culture, and all of its various nuances.

Specialized managers use local insights to exploit inefficiencies and regulatory differences that passive global indices typically overlook.

5. Private Markets

Extreme information asymmetry exists due to a lack of public data.

There’s also a massive amount of opportunities in private markets that aren’t available in public markets.

Managers here drive returns through proprietary deal sourcing, operational restructuring, and strategic guidance that’s generally unavailable in public exchanges.

6. Process-Driven Investments/Returns Streams

Similar to what we mentioned in the private markets section, but process-oriented investments are often a key source of return.

These might be more skill-driven. That comes with the trade-off that many of them are not passive. Sometimes it’s like buying yourself a job.

Some are very effort-intensive in the early going, but then more passive once a certain amount of work has been put in.

Whatever the case, be sure you have a definable and sustainable edge. And also make sure that it’s repeatable and isn’t just about lucking out or might appear every blue moon.

For example, selling annual S&P 500 volatility at 35% might have better than normal odds of working out if you trade it well. But it’s also something that’s very rare and unlikely to repeat itself very often.

Theoretical Arguments Against Stock Picking

While specific niches like small-cap or emerging markets may offer room for specialized insight, the ability to consistently pick winners in the large-cap market is heavily contested by financial theory.

William Sharpe (Nobel Laureate)

Nobel Prize-winning economist William Sharpe provided perhaps the harshest critique of the industry in his 1991 paper, “The Arithmetic of Active Management.”

As he wrote:

Before costs, active and passive returns are equal. After costs, active returns are lower due to higher active management costs.

Sharpe’s argument is not based on market trends, but on immutable mathematical laws. He posits that the “market portfolio” represents the sum of all holdings.

If passive investors hold a pro-rata slice of the market, then active managers, as a group, must hold the remaining slice, which is also identical to the market.

Therefore, before fees, the average return of active managers must equal the return of the market. However, active management involves high transaction costs, research expenses, and management fees.

Once these expenses are subtracted, the average active manager must mathematically underperform the passive benchmark.

In Sharpe’s view, the stock-picker’s market is a negative-sum game.

Of course, this is all speaking categorically, not individually.

Eugene Fama and Kenneth French

Building on this, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French used simulations to analyze fund returns over decades.

They sought to distinguish genuine skill from luck.

Simulating thousands of portfolio outcomes, they demonstrated that in any random distribution, some participants will inevitably reside at the far right of the bell curve (the “outliers”).

Their research concluded that the number of managers with long track records of beating the market is statistically indistinguishable from what one would expect by pure chance.

A “star” stock picker is likely just a lucky coin-flipper who hit heads ten times in a row.

Criticism of Academic Arguments

Academics will naturally believe in efficient markets and lack of skill differential relative to practitioners who have more practical experience and see the nuances.

Sharpe’s arithmetic is mathematically sound for the aggregate, it ignores the nuances of individual execution.

Just as academic research doesn’t believe in “hot hands” in sports, actual athletes generally do believe that getting in a certain performance tier is a real thing. That it isn’t simply luck but an edge or increase in performance, if only temporary.

Financial theorists may overlook the tangible edge of experience and skill.

Practitioners argue that markets aren’t perfectly efficient and they can and do allow astute managers to extract alpha before the window – as is often the case – closes as more pick up on the edge and it attracts competition.

The Persistence Problem (S&P Scorecard)

Consistency Data

Real-world data from S&P Global reinforces the academic skepticism. If stock picking were a durable skill, top performers should be able to repeat their success year over year.

However, the S&P “Persistence Scorecard” reveals a stark lack of staying power.

As of the end of last year, only 2.4% of large-capitalization stock funds could consistently remain in the top half of all funds for five consecutive years.

And zero domestic top-quartile funds managed to maintain that top-tier status for five years straight.

Implication

The implication is that consistency in active management is difficult, and arguably worse than random chance.

For traders/investors, this turns conventional wisdom on its head. The data suggests that pouring money into a fund because it just had a “winning” streak is a flaw in logic.

Because performance tends to mean-revert, picking the worst manager might not necessarily be a worse bet than chasing the manager who just finished first.

Index Funds Over Active Management?

This makes a case for index funds. If you need or want specific exposure to something, bet less on the specific strategy and more about what it’s doing for you (e.g., tail risk hedging, strategies unavailable in public markets).

Think more in terms of strategy and de-emphasize funds that are overly tactical.