Pure Yield Income Strategy for the Stock Market

Below we are going to go through an example of a pure yield income strategy for the stock market. The strategy is designed to deliver yield as opposed to capital growth.

Top Brokers For The Pure Yield Income Strategy

Let’s say you have $100,000 to invest.

And you identify Altria (MO) stock as one trading at a price of $45 and an annual dividend of $3.92 per share, covered by its earnings.

As a mature business, Altria can afford to pay out more to its shareholders rather than pushing more into capital investment to fund growth initiatives (in such cases, capital appreciation is a bigger influence).

And let’s say you don’t care about capital appreciation part and just want a pure yield approach.

The Setup

It involves two parts:

1) Sell ATM Calls

You can sell at-the-money (ATM) calls on the stock. Looking out about a year, ATM calls on Altria are going for $3.40 per share.

So now you have a dividend of $3.92 per share and an options premium of $3.40 per share.

Combined, that’s $7.32 per share.

Dividing that income by the share price – $7.32 by $45, that comes to 16.3%.

Based on how many shares you’re going long (figured up in the point below), you would sell 22 ATM calls, which covers 2,200 shares.

2) Buying the Stock

For $100,000, that can buy you about 2,200 shares.

Technically it’s 2,222 ($100,000 divided by $45), but we’re rounding since options contracts are sold in increments of 100 shares per contract.

With 2,200 shares and $7.32 per share, that can produce about $16,000 in income within the next 12 months after taking into account transaction costs.

How can you lose money?

You can lose money by the shares losing value mark-to-market.

This is always a material risk.

Since you’re generating $7.32 of income per share under this setup, your breakeven is your net income per share minus your purchase price:

7.32/45 = 16.3% loss per share

1 – .163 = .837 = 83.7% of share purchase price

$45 * .837 = $37.68

So, under this setup, you will make money if your share price remains above $37.68.

You’ll lose money if it goes below.

You will not make any additional money for the share price going above $45 because the call options with a 45 strike cap your potential gains.

What are your other risks?

Your main other risk involves options assignment.

In other words, if you are short an option and it is in-the-money, this gives the option’s buyer the right to buy the stock at any time. Each option contract represents 100 shares of stock.

Early option is available for American-style options and not available for European-style options.

If you trade US equities and options on US equities, you can be pretty sure that early assignment is a possibility.

Early assignment can happen at any point for American-style options when ITM.

In particular, when a stock carries a dividend with it, the option’s buyer is going to be more motivated to exercise the option.

This is so the trader can capture the dividend before the ex-dividend date.

Does this always happen? No.

But using some basic math (which we’ll provide an example of later), you can better understand the economic incentives of the other party and accordingly predict the likelihood of being assigned early.

Likewise, if you are an option buyer, you can also go through the math to determine whether it’s in your best interest to exercise early.

Determining which options are quality candidates for early exercise lies in what’s known as an option’s extrinsic value.

Extrinsic Value

The extrinsic value is made up of two parts:

- its time value, and

- the implied volatility of the underlying security

The more volatile the underlying security is expected to be, the greater the premium of the option, all else equal.

Moreover, holding all else equal, options further away from expiry (i.e., more days remaining until expiration) have more value than those closer to expiry.

The longer the time remaining, the more that can happen to influence the price of the stock, causing the premium to go up.

Option Price Component

An option’s price is comprised of two components:

- its intrinsic value – or the amount by which the option is in-the-money (ITM), and

- its extrinsic value – the value above its intrinsic value (i.e., time value plus implied volatility)

If you are the owner of an ITM call on a stock that’s about to go ex-dividend, you will have the choice of either holding onto the option, or exercising it to collect the dividend. (You might also have another motivation, but dividend capture is the most common one.)

Should you exercise to capture the dividend? It’ll depend.

If you choose to exercise the call, you are exchanging the call for the underlying security at the strike price of the option. Any remaining extrinsic value in the call is foregone.

This may be risky because by owning the security, you now bear the entire downside, as opposed to having a limited risk structure in place with the call option.

What this means is that if the dividend you could collect has more value than the extrinsic value of the option, this could be a worthwhile candidate for early exercise.

Example

Using the example used in this article, let’s say you’re on the other side of the option and you own a 45 strike on an Altria (MO) call option and the stock sits at 46, leaving the call option ITM.

Let’s say the value of the option is $4.00 per share ($400 per contract). And this option expires in 11 months and has four separate quarterly dividend distribution payments remaining of $0.98 per share ($3.92 per share for the year and over the duration of the options contract).

The intrinsic value of the option is easy to figure out. We simply take the price of the underlying ($46) and subtract from the strike price ($45). That gives you $1.00.

That means the extrinsic value of the option is the rest of it – $4.00 minus $1.00, which leaves $3.00.

The value of the next dividend distribution is $0.98.

Because the value of the dividend is lower than the extrinsic value of the option ($3.00), that means you would likely not exercise early. Some people might, as the option conveys to them that right. But most won’t.

Most options assignment occurs in the final ex-dividend date leading up to expiration.

This is when the extrinsic value of the option will be the lowest (due to time decay), and may leave the dividend payment higher than the extrinsic value.

Accordingly, this will commonly trigger early assignment.

What should you do if you are likely to get assigned early?

You have a few options.

1) You can roll your option out further.

In other words, if you believe you are likely to get assigned early, you can cover your position in your current options contract and move into one further out that has an extrinsic value above the upcoming dividend payment.

You can do this by lengthening the maturity (e.g., Jan ’22 call –> Jun ’22 call) or choosing a strike price that’s further out of the money or less in the money (e.g., 45 call –> 50 call).

2) You can close your entire position.

This would especially be important if being assigned stock would whittle down your excess liquidity cushion to the point of triggering a margin call or giving you little wiggle room.

If you do get assigned stock and run into margin issues, then you should close out your position immediately, or else your broker will do it for you.

3) You can buy an equal amount of stock you already have open to still collect the same amount of dividend.

To complete the same covered call structure, you could sell either an OTM option (where no early exercise would be possible) or an ITM or ATM option whose extrinsic value is less than the upcoming dividend.

Again, any ITM option is fair game for early assignment, so be careful.

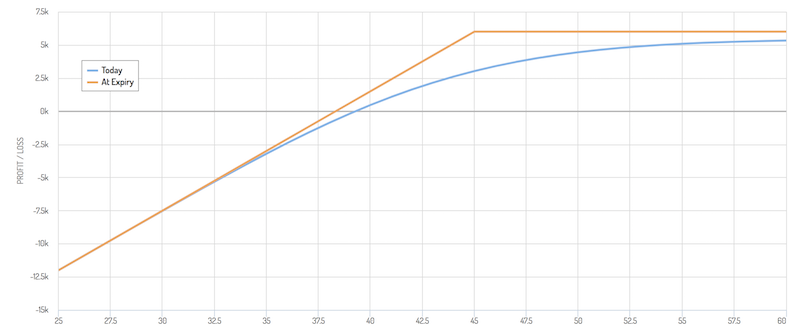

Payoff Diagram

Going back to our original setup:

1) Buy X00 shares of Altria (MO)

2) Short X long-dated calls of the stock at a 45 strike to generate a covered call structure.

This represents your payoff diagram:

It illustrates the reality that if the stock goes in your favor you make the income regardless of what happens.

However, if something goes very wrong, then you can lose a large amount.

From a risk management perspective, you may want to buy long-dated OTM puts to protect your downside. Or you can make your position sizes so small relative to your equity – i.e., diversify – that a trade gone bad won’t hurt you that much.

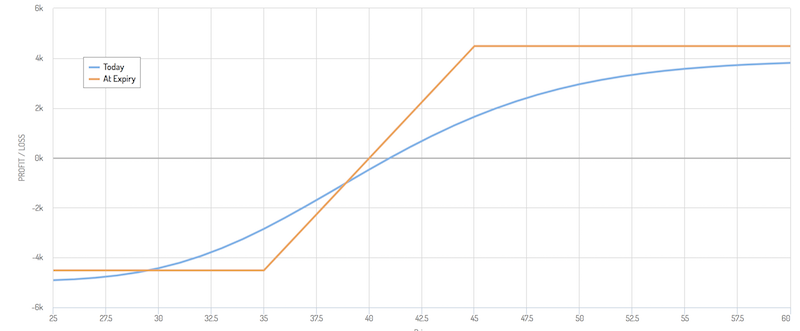

But if you wanted to go the options route, this can be done, for example, by buying 35 puts at the same expiry as your calls.

This reduces your maximum loss to a little under $3 per share.

This would also limit your upside relative to keeping it unhedged.

Your payoff diagram would therefore look like the following:

But note that your odds of making money are materially higher than your odds of losing money. Your starting point is $45 per share, not $35.

This means taking into account the probabilities – there’s greater than a 50 percent chance that your ending price will be above the strike and you’ll get the maximum amount possible. There’s less than a 15 percent chance that the price will end below $35 per share and you’ll suffer the maximum loss possible.

The expected value of the trade is positive.

This is one of the pitfalls of options payoff diagrams. They show outcomes in purely linear terms when the reality is that outcomes are better modeled in terms of distributions.

If price is currently $45, then it’s more likely to be $45 in a future period and less likely to be at $35, $55, or some other distant price.

But always know how bad things can get and take steps to avoid what can punch a large hole in your account.

You can take steps to limit drawdowns by having a well-diversified portfolio, but any type of concentrated or idiosyncratic risk needs to be considered and dealt with in a prudent manner.

Limiting losses is your most important consideration and carries material compounding effects over the long run.

Pure Yield Income Strategy: What This Amounts To

In this example, we’ve basically done what’s simply known as the covered call, which we covered in more depth in a previous article.

It’s a simple setup that involves the following:

1. Buy 100 shares of a stock

2. Sell 1 options contract on said stock

These are particularly effective yield enhancers when implied volatility on a particular instrument is higher than what’s likely to transpire. People pay more money for options when volatility is higher.

They serve as a source of an unlimited upside/limited downside trade structure and also as a prudent source of hedging. The demand for these becomes higher in more turbulent environments.

It can also be useful as part of a pure yield income strategy when markets are high. Any decline in shares can be offset partially or completely through the income derived from the option.

The covered call strategy is popular among both individual and institutional investors because of its attractive risk-adjusted returns.

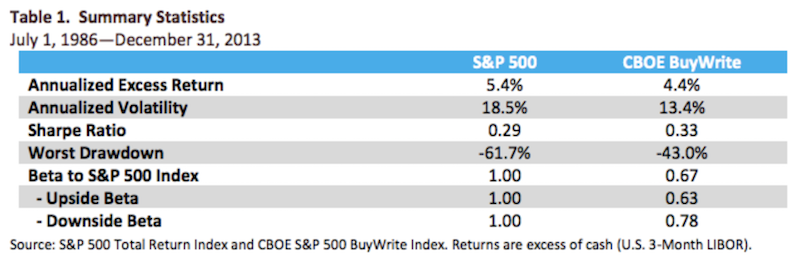

By comparing the return of the S&P 500 to the return of the CBOE S&P 500 Buy Write Index (BXD), the industry’s popular covered call benchmark, we can see that it has had returns comparable with that of the S&P 500 (about 100bps lower per year) but with only about two-thirds of the volatility.

Here are the results of one such study from 1986 to 2013:

The advantages of the covered call in comparison to a standard delta-1 position – i.e., being long the stock as a vanilla position – include lower volatility, lower beta to the equity market, and lower tail risk given the income from the option.

As a result, the strategy has produced higher returns in risk-adjusted terms, as reflected in the Sharpe ratio, a common measure of excess returns over excess risks.