Cash-Futures Basis Arbitrage

Arbitrage, at its core, is the art of exploiting price differences for the same asset across different markets.

Cash-futures basis arbitrage is a specific type of arbitrage that leverages the relationship between the cash (or spot) market and the futures market for a given underlying asset.

Key Takeaways – Cash-Futures Basis Arbitrage

- Understand the Basis – The basis is a key metric that indicates the difference between the spot and futures markets. It reflects market dynamics like cost of carry and supply-demand. Arb opportunities come up when the basis deviates from its fair value.

- Leverage Convergence – Profits are “locked in” as the basis narrows toward zero near futures expiry, aligning cash and futures prices.

- Two-Sided Strategy – Arbitrage involves buying the cheaper asset (cash or futures) and selling the more expensive one to take advantage of pricing discrepancies.

- Manage Risks – Basis risk, execution challenges, and margin requirements can impact profits. Accurate calculations and efficient trade execution are important.

The Foundations: Cash, Futures, and the Basis

Before we go into the strategy itself, let’s clarify the key terms:

Cash Market (or Spot Market)

This is where assets are traded for immediate delivery and payment.

For example, if you buy a stock on a stock exchange, you’re participating in the cash market.

You pay the current market price, and the shares are transferred to your account.

The trade is settled immediately, and the payment is exchanged.

Futures Market

In the futures market, participants enter into contracts to buy or sell a specific asset at a predetermined price on a specified future date.

These are standardized contracts traded on futures exchanges.

Futures contracts are agreements to buy or sell an asset, such as a commodity, currency, or index, at a future date and price.

Basis

The basis is the difference between the cash price of an asset and the price of the futures contract for that same asset.

In equation format:

Basis = Cash Price – Futures Price

The basis can be positive or negative, and it fluctuates constantly based on markets.

The Cost of Carry: A Key Factor in Basis

The basis often reflects something called the “cost of carry.”

This represents the costs associated with holding an asset until the futures contract expires.

Think of it as the expense of storing a commodity like wheat or gold, or the foregone interest you could have earned by investing the money elsewhere, instead of using the capital to buy the asset.

Stock futures will generally include the cost of borrowing, so the futures prices will typically be higher than the spot price in the cash market.

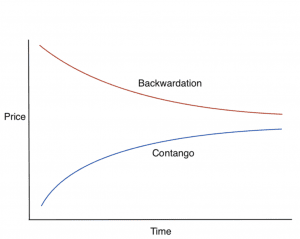

Positive Basis (Contango)

When the futures price is higher than the cash price, we say the market is in “contango.”

This often occurs when the cost of carry is positive, such as storage costs for physical commodities.

A positive basis implies that the market anticipates higher prices in the future, often due to storage costs or expected supply shortages.

Negative Basis (Backwardation)

When the futures price is lower than the cash price, the market is in “backwardation.”

This can happen when there’s a shortage of the asset in the cash market, or when there’s a high demand for immediate delivery of the asset.

A negative basis indicates a premium on immediate delivery – i.e., could suggest strong demand or supply constraints in the spot market.

How Cash-Futures Basis Arbitrage Works: A Two-Sided Trade

The arbitrage opportunity arises when the basis deviates significantly from the “fair” value, which is typically determined by the cost of carry.

A savvy arbitrageur (or an arbitrageur’s algorithms/computer system) spots these discrepancies and takes advantage of them with a two-sided trade:

Buying the Cheaper Asset

If the basis is too wide (e.g., the futures price is excessively high compared to the cash price, considering the cost of carry), the arbitrageur will buy the asset in the cash market (where it’s relatively cheaper).

Selling the More Expensive Asset

Simultaneously, the arbitrageur will sell an equivalent amount of the asset in the futures market (where it’s relatively more expensive).

The arbitrageur takes a short position in the futures market to lock in the current price for future delivery.

The Convergence Principle: Locking in Profits

The key to this strategy is the expectation that the basis will eventually converge, or narrow, as the futures contract approaches its expiration date.

In an ideal world, at the contract’s expiry, the futures price should equal the cash price (because a futures contract essentially becomes a cash transaction at that point).

However, the basis rarely goes to zero.

Profit at Expiry

When the futures contract expires, the arbitrageur can either:

- Deliver the asset they bought in the cash market against the futures contract they sold.

- Offset their futures position by buying an equivalent futures contract in the market.

The profit is essentially “locked in” at the time of initiating the trade because the arbitrageur knows the difference between the price they paid in the cash market and the price they will receive (or pay) in the futures market.

This difference, less any transaction costs and the cost of carry, represents their arbitrage profit.

The arbitrage profit is guaranteed because the basis will converge toward zero at the contract’s expiration.

Example: Arbitraging the Corn Market

Let’s say the current cash price for corn is $4.00 per bushel.

A futures contract expiring in three months is trading at $4.25 per bushel.

Let’s assume the cost of carry (storage, interest, etc.) for three months is $0.10 per bushel.

- Basis = $4.00 (Cash) – $4.25 (Futures) = -$0.25

- Fair Value of Basis = -$0.10 (Cost of Carry)

The basis is wider than it should be. The futures price is too high relative to the cash price, given the cost of carry. This presents an arbitrage opportunity.

The Arbitrage Trade

- Buy Corn in the Cash Market – The arbitrageur buys corn at $4.00 per bushel.

- Sell Corn Futures – Simultaneously, they sell corn futures contracts expiring in three months at $4.25 per bushel.

At Expiry (Assuming Convergence)

Let’s assume the cash price at expiry is $4.15 per bushel (it could be anything, but the basis will narrow). The arbitrageur:

- Delivers the Corn – Delivers the corn they bought at $4.00 against the futures contract, receiving $4.25.

- Profit = $4.25 (Futures Price) – $4.00 (Cash Price) – $0.10 (Cost of Carry) = $0.15 per bushel profit.

Real-World Business Examples

Cash-futures basis arbitrage isn’t just a financial market thing. It has important real-world implications.

Farmers often use futures markets to stabilize their income by shorting the commodities they grow or produce.

When a farmer grows crops or raises livestock, they’re naturally “long” in the physical market, meaning they own the actual product and are exposed to the risk of price falls.

To manage this risk, they can sell futures contracts, effectively locking in a price for their goods in advance.

So, by shorting futures, farmers hedge against potential price declines.

If market prices fall, the profits from their short futures position offset the lower prices they receive for their physical commodities.

Conversely, if prices rise, the losses on the futures contracts are balanced by higher market prices for their goods.

This strategy doesn’t try to maximize profits but to reduce uncertainty, so that they have more stable cash flow and helps farmers cover their production costs and financial obligations.

Hedging in this way is a key tool for risk management in agriculture.

It allows farmers to focus on their operations without being overly vulnerable to market fluctuations.

Naturally, a farmer will feel much more comfortable having their business based off of what they produce rather than how lucky they are on prices when selling into the market – especially given it’s not uncommon for many commodities to move 5% or more in a single day.

Risks & Considerations

There are various risks.

Basis Risk

The most significant risk is that the basis may not converge as expected.

Unexpected market events, changes in supply and demand, or errors in calculating the cost of carry can all affect the basis.

Changes in interest rates or storage costs can also impact the cost of carry.

Execution Risk

Successfully executing the trades in both the cash and futures markets at the desired prices can be challenging.

Slippage, where the actual execution price differs from the expected price, can erode profits.

Slippage can occur due to market volatility or large order sizes.

Futures markets can be illiquid, as can some cash markets as well.

Counterparty Risk

In the futures market, there’s a risk that the counterparty to the contract may default.

However, futures exchanges typically have clearinghouses that act as intermediaries and guarantee the performance of contracts.

This risk is reduced by the use of clearinghouses.

Margin Requirements

Futures trading requires margin, which is a deposit of funds to cover potential losses.

Changes in margin requirements can force an arbitrageur to close their position prematurely, potentially at a loss.

Margin calls can occur if the market moves against the arbitrageur’s position.

LTCM was a hedge fund that famously blew up in 1998 by leveraging basis trades and not understanding how their own positioning was impacting the correlations of their trades.