Important WSJ Article on Accounting Fraud in China

Last Friday, the Wall Street Journal published a very important article regarding the rampant accounting fraud, financial reporting improprieties, and securities infractions that occurs in the Chinese capital markets.

For many day traders, prop traders, and high-frequency algorithmic trading operations, fundamentals are often of secondary importance. However, fundamentals are part of it and accurate derivations of fundamental value can matter in terms of how far something can move if a catalyst enters into the picture to move a market.

Moreover, if you have a longer-term trading account where you invest (for retirement or otherwise), what your investments are really worth matters in the long-run.

Many Chinese public companies have very questionable accounting, including some of the largest and most well-known companies. This is easy to get away with when capital is freely available, economic growth is steady, and markets are broadly under-policed. But downturns in the economy make keeping up the charade more difficult and liquidity issues start being exposed.

As Chinese growth slows to its natural equilibrium based on productivity and labor force growth trends (2 to 3 percent), down from its reported 6 to 7 percent, this will uncover companies that are not as healthy as they purport to be. Risk appetite and access to capital become scarcer as growth declines.

Alibaba Example

Alibaba (BABA) is one of China’s largest public companies. It’s often hailed as the “Amazon of China”.

Company management teams often peddle these narratives – whether accurate or specious – because they’re easy to grasp onto and emotionally alluring. People like narratives and stories. We like heroes overcoming obstacles. It’s a type of subliminal thing that’s not particularly productive to investing in a rational way unless there’s some logical basis for tying it to a company’s value creation process.

Alibaba has a complex web of hundreds of subsidiaries, variable interest entities (VIEs), and separate operating entities – a little more than half in China and the others in the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Singapore, and other tax havens. And they all do business with each other. Yet they exclude most of the related party disclosures among “investees” from its filings.

Where are those, why do they exclude them, and how can investors feel comfortable taking a bottom-up approach to a company like that when they can’t verify what’s actually going on in the accounting? Are they going by the emotionally alluring “Amazon of China” narrative and trust that they’re genuinely getting a piece of a $400 billion enterprise?

So much of what goes on at Alibaba isn’t on the balance sheet with these “VIE enhancement” structures. There are tons of off-balance-sheet arrangements, and often these accounting maneuvers are designed to conceal. When Jack Ma announced his retirement in September 2018, he sold various Alibaba VIEs to buyers whose identities were unknown and for unknown reasons.

Alibaba already trades at a premium to its supposed US comparison, Amazon (AMZN). I also believe they’re inflating their numbers with all their incestuous relationships between subsidiaries, VIEs, and separate entities, which means the premium is even larger. Its EBITDA multiple is 34x (taken at face value) vs. 32x for AMZN. Its revenue multiple is 7.5x vs. 4.0x for AMZN.

Their return on invested capital (ROIC) on non-investment-related net assets is also below their cost of capital. (Their capital is equity, as there is no net debt.) And going sequentially, their ROIC is scaling negatively. That means growth doesn’t actually help them at this point and is counterproductive. Their cloud initiatives aren’t the problem.

Alibaba’s primary business model is advertising-based, which is “asset-lite”. Yet the company has voracious capital needs. Amazon employs $42 billion in capital and Alibaba $78 billion. Yet Amazon’s annual revenues are $242 billion on a trailing-twelve-months basis and Alibaba’s are (supposedly) $56.2 billion.

In other words, Alibaba has a capital base 86 percent larger, but generating just 23 percent of the revenue. Amazon’s revenue off capital employed ratio is 8x higher than that of Alibaba’s.

And Alibaba’s capital deployment is up approximately 40 percent year-over-year.

For a company supposedly generating $13.1 billion per year in net income, why is that?

Why do they need to raise tens of billions in extra capital if they have all this cash flow? Where are the related party disclosures that would help people analyze what’s going on accounting-wise? There are many points of contention with Alibaba’s financial reporting.

Alibaba is no Google, Amazon, etc. If you have a reasonable accounting background, you can study Google and Amazon. You can’t study Alibaba.

But, for now, back to the WSJ article:

Some of the best quotes

“With economic growth at its slowest since at least 1992, investors and analysts say many companies are experiencing financial distress, which in turn is revealing accounting problems that were easier to hide when credit was freely available and businesses were growing rapidly.”

This is normally how accounting fraud gets revealed. Unfortunately, you can have more confidence in management’s ability to make up phony numbers than you can in regulators ability to catch the fact that they are fake, within reasonable suspicion.

While companies can fake their revenue, margins, profitability, and other numbers printed, they can’t fake the reality of running out of cash if and when it does happen.

“The reliability of financial statements is one of several challenges facing investors in China. There are also question marks over the quality of local credit ratings and official economic data, while critical commentary by analysts and investors is often censored.”

As China looks to integrate its financial system into the world markets, many investors are eager to tap into the growth potential and burgeoning liquidity of the world’s second-largest economy – and, if managed well, what can be the world’s largest economy within the next 15 or so years.

This has incentivized some businesses within China to take advantage of this foreign exuberance and cut corners. Moreover, US regulators, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in particular, can’t inspect the Chinese auditors of companies that trade on US exchanges. In other words, they can’t get information as it pertains to investigations into Chinese companies. This makes getting away with financial fraud much easier. So, if you end up investing in what turns out to be a fraud, you’re pretty much on your own.

Moreover, it’s important for traders to understand that audits are not particularly useful anyway. They aren’t really “audits” in terms of what the word conveys (an authoritative inspection or review of accounts by an independent body). They are actually limited compliance reviews.

Audits are like spell check on Word – they’re made to find trivial errors, not the big mistakes. Audit isn’t an accurate term. The term itself is made to convey the idea of integrity to a financial report. In reality, it’s simply a delimited compliance review of GAAP, IFRS, or whatever the accounting system is. They should be called “compliance reviews” because that’s what they actually are. They’re not designed to catch fraud; they’re made to catch material, but unintentional bookkeeping errors.

“There has long been suspicion that Chinese companies have a tendency to fabricate results when necessary. And that seems to be a well-grounded concern,” said Paul Gillis, an accounting professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management.

Chinese ADRs are hard to analyze because you don’t get the full picture. You have consolidated line items, but you don’t know what the actual accounting is behind many of those.

“Mr. Gillis said part of the reason is that it is extremely difficult to bet against companies by selling stocks short in China. “It’s short sellers who tend to identify most of the fraudulent companies because they have the incentives to do so.’”

He’s absolutely correct. Fundamental short sellers are a very important element of society. Short sellers are the main group with a direct incentive to actively expose corporate fraud and misdeeds. Whistleblowers are valuable, but are often unsophisticated and don’t get through to regulators like SEC enforcement. Media is beholden to desires of editors and advertisers, reporters are often limited in the depth of their knowledge and are commonly under deadline pressures and resource constraints.

John Carreyrou and his work on Theranos is the exception, not the rule. Unions have a conflict of interest; they will fight, but only to an extent.

Regulators are beset by bureaucratic inertia, regulatory capture, shifting political winds, and are generally interested in easy battles they understand and know they can win. Mark Cuban’s advice to Elon Musk, who was charged with securities fraud in September 2018, to aggressively posture by hiring former SEC staff to defend his case was no accident. Short sellers are the only ones properly incentivized.

“Auditors declined to endorse—or endorsed only partially—a record 219 annual reports last year, nearly double the 113 in the previous year, according to Wind Information Co., a data provider. These actions suggest an auditor has found issues with the results or has doubts about the company’s status as a going concern.”

Very few accounting people take classes in fraud, securities laws, internal controls, or criminology or the incentives to commit crime. So, they often don’t know what to look for – for example, what types of ratios to look at and their trends.

For example, if employee compensation as a percentage of revenue is increasing over time, what might that tell you to investigate further? It might mean that they’re capitalizing future salaries and wages payments upfront and bucketing them into a balance sheet account. In certain cases, getting expenses off the balance sheet to overstate net income is a form of accounting fraud.

If an automotive manufacturer is misclassifying what are rightly called warranty-related expenses into “goodwill / service” and under-reserving for warranties, this has the effect of inflating gross margins. It overstates net income through low accruals.

Auditors are largely trained to be process-oriented, not judgmental. They’re supposed to be the first line of defense, but they’re really no match for even mildly sophisticated corporate/white-collar fraud.

Regulators, the supposed backstop, also have trouble catching fraud in most jurisdictions because they’re undermanned and understaffed. Moreover, the SEC is an organization of securities lawyers. Having high financial acumen is of tertiary importance.

White-collar crime is more sophisticated and more difficult to investigate than blue-collar crime, yet the resources dedicated to it are relatively minimal by comparison. The SEC doesn’t have the manpower to police the capital markets of the United States. There’s a false sense of security even in the US that companies are regulated and properly audited to ensure their financial reports are thoroughly and accurately vetted.

“Amy Lin, a Shanghai-based senior analyst at Capital Securities, said the cost of breaking the law was too low in China. The maximum fine for false financial disclosures is 600,000 yuan ($87,000), while the top criminal punishment for hiding or destroying accounting records is a prison term of five years and a fine of up to 200,000 yuan.”

In the US, the federal government has effectively decriminalized securities fraud to the level of an ordinary civil tort (i.e., minor fines and other relatively trifling punitive measures relative to the level of ill-gotten gains).

“On July 26, the market regulator said it would increase prison terms and fines for capital-markets misdeeds, and would revoke licenses of intermediaries, including accounting firms, that failed to fulfill their duties.”

Corporate fraud is rampant in many countries because they perceive the reward to be higher than the risk. They don’t believe they’ll ever do time let alone ever face criminal charges if there’s an investigation.

Prosecuting frauds is not easy to do because the justice system is based on the presumption of innocence and most of these cases are built on circumstantial evidence that often doesn’t meet the standard required in the court system.

Now if people’s compensations are on the line this might have an influence. But the SEC (the main US watchdog) brings forward very few clawback cases. There’s a socialization of bad behavior. The companies pay for the individuals and effectively indemnify their bad behavior. Or the insurance companies are indemnifying the firms and paying for the companies’ mistakes. The consequences are socialized and the individual doesn’t have responsibility for their own actions.

As is often the case, all they do is pay a small fine relative to the level of illegitimate proceeds.

And even if firms are falsely reporting numbers and get caught, the regulators just tell them to fix their numbers. So, they fix them and the regulatory agencies walk away. Auditing firms have access to the bookkeeping and generally have a good to very good relationship with management. On the other hand, investors and outside accounting folks, all they have (in an official sense) are the SEC documents (e.g., 10-Qs, 8-Ks, etc.). Auditors simply conduct limited compliance reviews; they aren’t the police and are of little value in terms of catching fraud.

For example, there were fifteen different legal, financial, and accounting firms involved in HP’s 2011 acquisition of Autonomy. Not one of them raised red flags and everyone missed the accounting irregularities and disclosure “oversights”.

When they’re paid by the company to work for them, these people will be incentivized to want the deal to get done, so it probably will be.

“Independent audits” are fundamentally there to protect the company, not the employees, vendors, or consumers. Investors tend to think of auditors as guardians, but this couldn’t be the further from the truth. When accounting investigations do occur, they typically align with management teams because they don’t want their negligence exposed.

“’The authorities have a clear intention to use the outburst of financial fraud as an opportunity to clean up the market, partly because they have limited capacity to bail out all the troubled companies,” said Shen Meng, director at Chanson & Co., a Beijing-based boutique investment bank.”

Unfortunately, the incentive isn’t about truly upholding the integrity of financial information off which our financial system is heavily predicated upon. Rather, when various forms of impropriety are uncovered and companies aren’t as healthy as they’ve been portraying themselves as, this puts a strain on sovereign finances.

For systemically important companies – whether these are banks or service- or tech-based businesses – central governments will be reluctant to let them fail because of their strategic significance to the advancement of their national interests. This is particularly true in state-directed economies such as China.

At the same time, bailing out failing enterprises comes at a cost. It can be a very large one depending on the extent of the problem (e.g., global banking system in 2008). Accordingly, holding private or semi-private companies to higher standards can be necessary to enforce discipline in financial reporting.

Corporate Accounting and Strategy in Various Stages of the Business Cycle

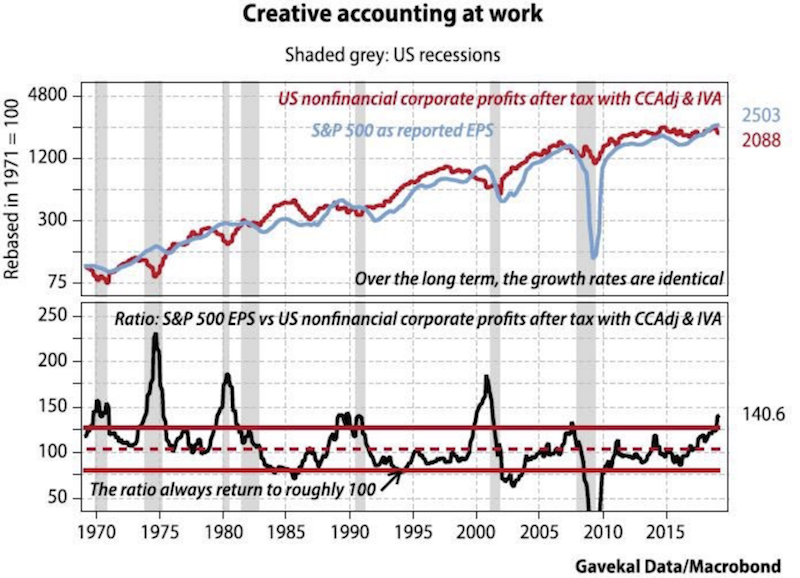

To the extent to which the data is available, the accounting quality of a country can be determined by comparing the aggregated individual company results to what you see in the economic or national-level accounting (i.e., nonfinancial corporate profits).

In some countries, however, the national-level accounting as compiled by government statistics and data agencies isn’t very accurate, so it must be done through other means (e.g., high-frequency output indicators, triangulation of other data points).

In the US, accounting “creativity” is on the rise more broadly when comparing national to aggregated individual results.

You will often see reported earnings run ahead of national-level earnings toward the later stage of the business cycle. They undershoot immediately after recessions.

Firms get more creative in the later stage of the business cycle because it becomes harder to meet embedded expectations. Asset prices rise, debt servicing rises relative to income, and forward rates of return on projects decline.

When companies don’t meet what analysts expect, they typically get punished. Moreover, management team are often compensated heavily through stock and stock option rewards and have the incentive to keep it elevated.

Once growth reaches an inflection point sometime in the middle of the economic cycle and decelerates, organic growth opportunities fade. As a result, reported earnings relatively late in the business cycle – where we are now in developed market economies – will tend to be a bit exaggerated as a whole.

This doesn’t just mean accounting adjustments or financial reporting tricks, but also financial engineering. Companies are more likely to shake up their corporate structures, whether it be via operations or capitalization. Operationally, this means mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures, where margins can be augmented by getting rid of less profitable divisions and improve scale through acquisitions.

Whenever pre-tax operating income stalls without increased capital costs offsetting the strategic desire to merge, it should be expected that M&A activity increases. There’s a reason why the top in M&A cycles (in total dollar volume) roughly accorded with tops in the previous two business cycles (Q3’07 and Q1’00). Total dollar M&A volume as a percent of US market value of equity is generally 11%-12%, though can get up toward 18%-20% late cycle and sub-5% early cycle.

Conclusion

To anyone trading or investing in Chinese equities on a fundamental basis, it’s important to be aware that the financial information reported by these firms is difficult or next to impossible to verify.

China is purportedly taking some steps to crackdown on financial fraud. Unfortunately, the reasoning largely isn’t to better police their capital markets because it’s the right thing to do. Rather, allowing companies to easily fool or outright defraud their investors creates economic inefficiencies and distortions when businesses are fed capital based off fraudulent information, which keeps otherwise poor businesses afloat or appear much healthier and valuable than they really are. Much of the burden can and will fall on sovereign finances when growth slows and capital is less freely available, which tends to expose the problems of companies who have been cooking the books.