Will 2019 Be Another Bad Year For The Stock Market?

2018 has been a mostly poor year for the stock market and financial assets more broadly. The S&P 500 is down, and most public companies are in a bear market globally. In other words, their stocks are down 20 percent or more from their peaks. Global earnings growth is still positive, but a combination of slowing growth and higher rates is making things less accommodative for asset prices.

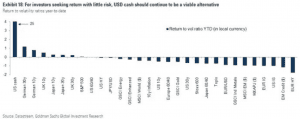

Only USD cash has seen high returns relative to volatility.

The S&P 500, the most followed stock benchmark globally, containing 500 of the largest public companies in the US, is expected to see earnings grow by about 9 percent in 2019.

Stock prices are a function of a future cash flows discounted back to the present. In other words, you pay a lump sum for a series of future cash flow payments.

What are cash flows?

They are what companies earn after taking into consideration any net expenditures that are not already expensed on the income statement.

The discount rate is an expected return on investment. If earnings rise faster than the discount rate increases, then stocks can be expected to go up. If the opposite is true (earnings rising slower than the discount rate increases), stocks will go down. Even if earnings decline, then stock can increase in value as long as a decline in rates is sufficient to more than offset the decline in earnings. (This is what happened in the US from Q1 2015 to Q3 2016.)

So if rates didn’t move at all, and earnings do come in at about 9 percent, then stocks should be expected to come in around that 9 percent.

Where Are Rates Likely to Go?

Earnings tend to be less volatile than interest rates. Accordingly, figuring out what rates are going to do tends to be of more use in figuring out where asset markets are likely to do.

What influences rates? Supply and demand for credit – e.g., loans, bonds, money market instruments, and other credit products (e.g., asset-backed securities, leveraged loans).

A lot of bonds have to be issued because of the US deficits, which will go higher in time, and there is very likely to be a shortage of buyers for them, which means credit costs are poised to continue rising and that’s a negative through the present value discounting effect. (As mentioned above, an asset is just the present value of future cash flows.)

Foreign central banks’ reserve growth is flat and these entities are close to being maxed on their allocations toward US Treasury bonds. Commercial banks’ reserve growth is about flat and don’t need much more in the way of liquid assets to satisfy regulatory requirements, so there is not much buying support there either. The US Federal Reserve is a seller as it unwinds its balance sheet. The ECB is no longer a net buyer of EU debt (where there will also be a shortage of bond buyers). Retail might soak up $500 billion through bond fund inflows, while pension funds and insurance companies will take in an estimated $550 billion to $700 billion. But even going with the top end of those range estimates, there’s a shortfall.

That means lower prices and higher yields.

The Fed gets one rate hike to work with in 2019 (20-basis point hike on the interest rate they pay on excess reserves) and just 10bps of tightening is priced into the curve 2 to 3 years out. Anything beyond that is a drag on financial assets.

Each 25-bp parallel shift in the yield curve has the effect of pushing US equities valuations down 4.8 percent, holding everything equal.

Looking one year out, US growth is priced to be around 2.5 percent and CPI inflation slightly above 2 percent, WTI oil priced at $53, and the US dollar is priced to fall 2 percent against developed market currencies.

Equities are priced to only give you an extra 3.7 percent of yield above 2-year Treasuries, which is an asset where you don’t have to worry about substantive price risks. This means that stocks don’t provide very much additional yield for a lot of extra price risk. So those look bad from a reward to risk perspective. (2,870 on the S&P 500 would put that extra yield at 3 percent, holding interest rates constant.)

Monetary policy is a drag through the selling of bonds (and potentially more rate hikes). And so will fiscal policy soon through the selling of US Treasuries to finance the US fiscal deficit. Fiscal stimulation – via the tax cuts and spending bill that were passed on November 2, 2017 – will pass through and be a drag on US economic growth in 2020 and 2021 though it adds about 0.35 to 0.40 percent to US GDP growth in 2019.

Conclusion

Through this lens, you probably wouldn’t find the vast majority of financial assets very attractive. The expected 9 percent earnings growth in stocks is likely to be offset to a degree by the volume of bond issuance and the lack of available buyers. If central banks ease (e.g., Fed reducing the rate at which it sells assets from its balance sheet), that would help ease the supply and demand issue in credit and also transfer through into equities. But this would represent a reversal from the current stance.

But this would provide a 2019 market outlook where one would likely be roughly neutral to stocks and short a range of US and EU credit. 2019 recession risks are nonetheless low as the ability to service debt from assets, income, and new borrowing is sufficient to attend to upcoming debt servicing obligations.