Are Stocks Overpriced?

Are stocks overpriced? At the most basic level, the valuation of stocks is a product of cash flows and the rate at which they’re discounted back to the present.

For example, to use real estate as an example, since most have some exposure to the real estate market and it’s another form of equity, let’s think about how would one value a property at a basic level.

First, you’d look at how much you could conceivably rent it for if you were to own it.

Second, you’d subtract out all expenses – e.g., interest expense (paying down the principal builds equity, an asset), net tax effects, insurance, homeowner’s association fees, maintenance, and other such considerations that might be jurisdictionally specific.

You would map out how that revenue and expense figures would change over time. If you have a fixed rate mortgage, your expense would remain constant over the life of the loan. However, you might consider that various other expenses will probably raise by the rate of inflation.

This stream of calculations – revenues minus expenses – would represent a series of cash flows. Then you’d discount these cash flows back to the present by an expected rate of return on your investment. This would represent the value of the property. To figure out the implied rate of returns, you could also triangulate that if you have data on revenue, expenses, and the current market price of the property. You could then determine whether this is too high or too low based on your expectations.

The same type of process follows for stocks.

Are we in a bubble?

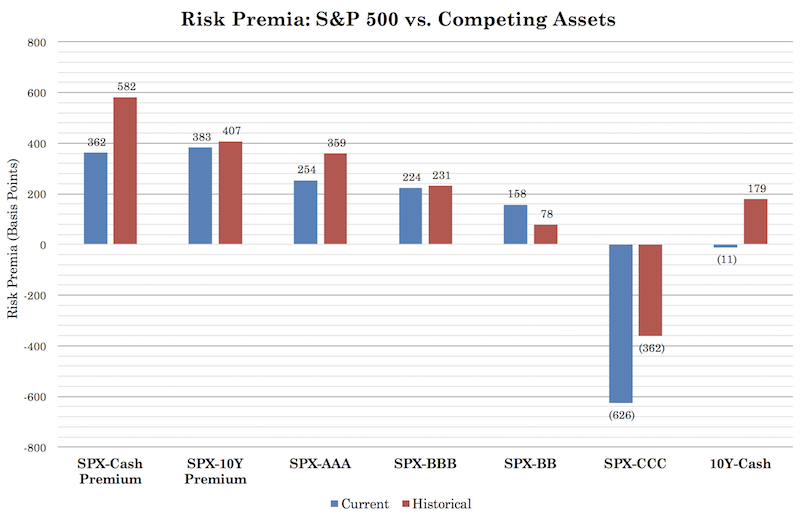

US stock prices don’t look that expensive in relation to bonds. Stocks offer an extra ~4 percent annualized yield over bonds in the belly in the yield curve. This isn’t much. After all, wiping out a few percent in the stock market can occur in just a day or two. But with interest rates low, and long-term rates approximating current cash rates, stocks naturally trade at higher earnings multiples.

If we take the current forward one-year earnings of SPX (around 170), divide by the current level of the index (2883 at the time of writing), this gives an implied yield of 5.9 percent. Relative to cash, this is about 4 percent extra, or about the same as longer-duration bonds – which currently yield even less than cash due to expectations of a forward easing of monetary policy.

This extra yield, called a “risk premium”, is not much relative to history but not wholly out of line relative to where interest rates are currently and the amount of liquidity fed into the financial system since the 2008 financial crisis via central bank asset purchases (through quantitative easing – i.e., “QE”).

The direct purpose of QE is to close the spreads of longer-duration assets to encourage lending and push investors into riskier assets, which helps create a “wealth effect”. This lowers their forward returns in both absolute terms and relative to other assets.

The effect of a bubble bursting on wealth

Following the bursting of an asset price bubble – which we are not in with respect to US stocks, but for explanatory purposes – the influence of asset price movements is more influential on economic growth rates than the impact of monetary policy.

Asset prices fall before earnings do. Based on the same concept, wealth (total assets minus total liabilities) contracts before income (what people earn by selling their goods and/or services, or through returns generated on financial assets).

In the early stages of a bubble bursting, stock prices fall and earnings have not yet contracted. Many will mistake this as “buying low” because they will ignore the influence of falling earnings and falling expected earnings. Markets are always looking ahead and discounting the future, so forward expectations are more important than what is happening right now.

This decline is also self-perpetuating. When wealth falls, followed by falling incomes, this results in a decline in creditworthiness. This holds back lending activity. In turn, this hits spending and lowers the pace of investment. Moreover, it becomes less appealing to buy financial assets on leverage while this process is unfolding.

Consequently, the fundamentals of riskier financial assets decline as softer economic activity leads corporate earnings to persistently underwhelm expectations. This causes traders and investors to sell assets, which drops asset prices further. Naturally, this will resemble a trend in the market. This has further negative feed-through effects on income and wealth.

The central bank will eventually need to arrest this decline by pushing nominal interest rates below nominal growth rates. This alleviates the worsening debt service burdens, which become more difficult as incomes decline and are insufficient to cover them. Economies will slow and eventually contract when debt servicing requirements compound faster than output.

To illustrate the importance of forward expectations and effective communication from policymakers, when US equities declined 20 percent in Q4 2018, the US Federal Reserve did not reverse this process by actually moving interest rates down or doing anything with their balance sheet. They provided a bottom in asset prices by revising their forward guidance with respect to future policy – namely, how far interest rates could rise further. Once the market gained wind of the fact that short-term rates would stay lower for longer and the term structure of rates shifted downward, this increased the present value of asset prices. This led to a conspicuous V-shaped recovery.

The influence of central banks

It is not an exaggeration to say that the central bank is responsible for almost all debt creation in an economy. Through their adjustments to monetary policy, they can either kill off credit creation or spur it along to the extent of the policy tools available to them to influence how lenders and borrowers are with each other.

Based on central banks’ statutory mandates, they primarily focus on growth within the context of price stability. They will tend to not focus on the amount of debt that’s being created and what that means for the purchase of investment assets.

Namely, when we discussed our three main equilibriums that economies and markets are perpetually fighting to get toward, central banks pay robust attention to one, but pay, in my view, insufficient attention to the other two.

Whether the economy is operating at a rate that is too high or too low relative to capacity is their chief focus.

How debt growth is trending relative to output – more precisely, how the growth in debt service payments is trending relative to income growth – is of secondary focus. It’s not explicitly in their mandate, although it’s exceptionally important. Failure to pay attention to this can result in credit bubbles – or asset inflation due to debt creation that is systemically dangerous.

These days, the Federal Reserve is required to run stress tests of how a certain confluence of economic events would impact the solvency of individual global systemically important (commercial / investment) banks (“GSIBs”). But asset bubbles can occur in all industries. The purchase of tech stocks on leverage in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s led to a recession in the US.

Most central bankers and traders missed the influence of residential housing on the global economy because they looked at the averages, which mostly concealed the extent of the problem, and extrapolated the past. Residential housing had mostly gone up in price for as far back as the data went in the US and hadn’t caused an asset price bubble of that magnitude for a very long time.

Moreover, most bubbles don’t result in excessive inflation in the real economy. They’re often disguised as a boom and policymakers don’t want to rain on the party. But it’s important to distinguish a boom from a bubble by doing the underlying calculations as to whether the debt being used to purchase the assets is likely to throw off the cash flow needed to service such debts going forward.

The new post-crisis regulations – e.g., Dodd-Frank, Fed stress tests of various systemically important banks – have in some respects reduced the odds of another crisis developing. But the issue is that each debt crisis occurs somewhat differently to different segments of the economy. And broadly speaking, how each can be handled is different as well. Households are different from corporations, which are different from sovereign governments.

Some parts of the economy also escape regulation. A more tightly related financial sector will tend to spawn a “shadow banking” sector that exists outside the scope of the normal regulatory framework. This occurs because it’s typically more profitable to adopt alternative legal structures that give more latitude in business operations.

As a notable example, post-crisis, trading operations largely went from depository commercial banks to prop trading firms and hedge funds, which were exempt from this legislation. And certain structures in the economy are never expected to run into issues.

The regulatory framework in the US and other developed markets also lacks sufficient flexibility to deal with an array of problems. For example, if there is a crisis emerging beyond the existing regulatory structure, there is no such thing as an “emergency act” where the heads of various representative branches of government – e.g., President, Federal Reserve chair, Senate majority leader, House majority leader – can declare that an emergency exists and bringing in knowledgeable people to determine what to do about it.

If I’m a buy and hold investor, what kind of returns might I get long-term?

In the US, with long-run real growth likely to come in somewhere between 1.7 and 2.0 percent, pending an uptick in productivity or growth in the labor force. Inflation will average around 2 percent or perhaps less.

Due to structural changes in the underlying economy – aging demographics and the pension and healthcare obligations associated with those, high debt levels relative to output (more debt servicing leads to less consumption and spending), labor arbitrage activity, and technological advances that have enhanced price transparency and ease of commerce – inflation is likely to remain low for a long time.

The additional influence of microeconomic financial engineering (namely, merger and acquisition activity, stock buybacks, and dividends) and macroeconomic financial engineering (interest rates and asset buying) will be lower going forward.

When central banks lower interest rates, and buy assets (quantitative easing) to lower rates further out on the yield curve, this pulls forward future returns. Interest rates have a limit in terms of how low they can go. Once spreads close, further asset purchases are no longer effective in achieving these goals.

In the US, the future effects of central bank induced financial engineering will be around 30 percent.

This is calculated by taking the area under the Treasury bond curve – some 150 to 200 basis points (1.5-2.0 percent) – and multiplying by the effective duration of stocks. Stocks currently yield some 5.9 percent in terms of their implied future yield as mentioned earlier in this article.

The inverse of this percentage yield is the duration. In other words, theoretically, if you invested a lump sum, how long would it take you to earn your money back without touching the principal? Earning 5.9 percent per year, that’s about 17 years (1 divided by .059).

Taking the range of 1.5-2.0 percent and multiplying by 17 gives you about 25 to 34 percent.

So, over the long-run, taking into account real economic growth, inflation, and financial engineering in its various forms, we expect US stocks to return 5 to 6 percent annualized over the long-run.

Are stocks overpriced right now?

Whether stocks are overvalued in absolute terms or relative to the amount of their risk is a personal question. It depends on your time horizon, risk tolerance, and other such factors that influence your trading or investment style.

As mentioned in the section above, we know that stocks are likely to yield about 5 to 6 percent annually long-term. This comes with expected annual volatility of some 15 percent per year. Government bonds give you 1.5 to 2 percent, with volatility ranging from practically nothing to beyond that of equities. All of that return will be eaten up by inflation if holding for the long-term. Cash yields just below 2 percent with no risk or volatility.

Is 5 to 6 percent compensation enough? Is that extra 3 to 4 percent extra yield for all that risk worth it? That’s not a question that’s easily answerable. It’s totally dependent on the person. The different wants, opinions, and motivations between different market participants is what makes a market.

All assets compete with each other. When you lower the interest rate of cash and of bonds, you lower their future expected returns. That feeds into risk assets, including stocks, real estate, private equity, and other asset types. These assets are not necessarily expensive in relationship to each other and they are not especially overvalued in relation to cash looking at the premiums between them.

Throughout the developed world, cash gives you about minus-1 percent in countries like Germany and Switzerland and just below 2 percent in the US. If you account for inflation, there is no real yield or it is negative. This pushes people into risk assets.

Central bank balance sheets still hold more than $15 trillion worth of financial assets. This $15 trillion went into the financial system. The central bank purchased securities; the financial system received cash in return. All of that money will inevitably go into assets. So, even though based on forward earnings multiples (17x), stocks are not that cheap, they are not particularly expensive relative to bonds or the rate of return you’d get holding your money in cash.

The most important thing going forward is central bank liquidity. Will they continue to lower interest rates? This will pull down cash rates and bond rates and push more investors into stocks to grab the extra yield. Lower rates also support lending activity, which feeds into spending and investment, which helps economic activity and creates the cash flows that underlie the value of asset prices.

Pricing in interest rate markets implies that all reserve currency central banks – the US Federal Reserve, ECB, BoJ, BoE – will ease moving forward. If they don’t follow through, this acts as a de facto tightening of policy. Markets always discount forward-looking information. If forward discounting changes, asset prices and forward returns change.

Where many traders get into trouble is that they tend to overemphasize assets that have done well in the very recent past. When stocks go up, they assume that it’s a better investment, rather than a more expensive one.

In reality, when asset prices go up, some of that price is simply pulling forward future returns. Moreover, when interest rates go down, this lengthens the duration of financial assets and makes them more sensitive to changes in interest rates.

So, even though the multiples (relative to earnings, EBITDA, etc.) are relatively high, this does not make equities inherently risky as long as interest rates don’t rise faster than what’s discounted into the forward curve. If ample liquidity is available, then it will get into assets.

The key question going forward is what kind of tools central banks have available to stimulate asset prices if their primary form of monetary policy (interest rate adjustments) is no longer effective because they’re already at zero or negative and secondary policy (asset buying, or QE) is no longer effective once forward bond spreads are comparable to cash rates and lack additional stimulatory effect.

Beyond that point, central banks will likely have to engage in currency depreciations. This will have some additional stimulatory impact on risk assets.

But currency depreciations also have their own limitations. It can include increased capital flight, to other countries and to inflation-hedge assets such as gold, due to undermined confidence in the currency. Imports become effectively more expensive because the currency doesn’t stretch as far in relative terms and hence hurts the consumer. Value is diminished for foreign holders of debt denominated in that currency. In general, currency depreciations are a hidden tax against those who have assets denominated in that currency and a benefit to those who have liabilities denominated in the currency.

What about the Trump impeachment inquiry? Does that matter?

Betting markets imply a 60 percent probability that an impeachment process will start. But they are also convinced that it does not matter and view the event as political theatre.

In terms of the second-order political strategy involved – namely, influencing public opinion on Trump and the knock-on effects of impacting the odds of the 2020 election, which is genuinely what markets are predominantly discounting as it pertains to this event – it is not likely to influence the voting behavior of independent voters or others on the margin according to recent poll data.

Conclusion

Equities appear expensive, near all-time highs in the US.

Nonetheless, they are not particularly expensive relative to cash or relative to other competing assets – e.g., bonds, private equity, real estate.

They are not, however, that attractive relative to their risks, offering 5 to 6 percent annualized long-run return relative to some 15 percent annualized volatility.

What complicates the picture in the near-term is that we are in the later stages of the business cycle. This means that the operating capacity rate of the economy is high and there’s the output and inflation dynamic that central bankers try to balance. They have a difficult time managing it toward the end of a business cycle. Sometimes “inflation” can mean real economy inflation, which puts excessive upward pressure on consumer and/or producer prices or it can mean the inflation as a result of asset bubbles, which can have systemically dangerous effects once they pop.

We are also in a situation where total debt relative to output is high and short-term interest rates are very low. This means there’s little ability to ease further to help rectify this debt issue going forward.

When business cycles end and there is sufficient room to lower short-term interest rates, central banks are relatively adept at handling these situations because they are well understood. However, when interest rates are already low and debt servicing burdens become difficult to manage, they cannot be rectified by the central bank changing the cost of credit. There will be a shortage of capable providers of credit and equity capital and shortage of capable recipients of capital.

Accordingly, we are likely to be in a low-returning environment for a long time moving forward. In the near-term, central banks will need to continue to ease monetary policy to the best extent of their powers to provide ample liquidity to the financial system, and the feed-through effect this has on elevating, or at least providing a floor under, asset prices.