Dollar Squeeze Is The Latest Drag on Asset Markets

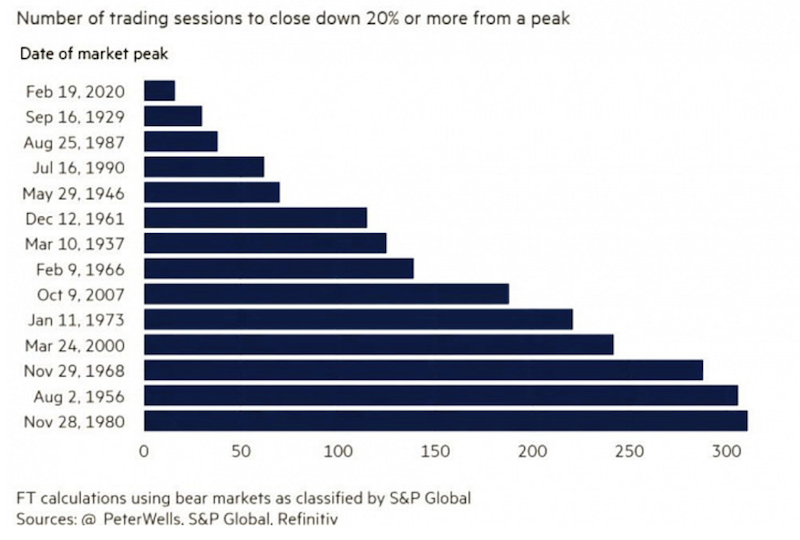

The 2020 bear market was the fastest drop on record, moving down 20 percent from its peak in only 16 days.

As we covered in previous articles, the coronavirus crash is not just about the virus itself, but the fact that debt is high relative to income and that central banks no longer have the capacity to stimulate in the usual ways.

Both of their traditional policy tools – the adjustment or short-term interest rates and bond purchases (also known as quantitative easing) – have run their course with short-term rates and longer-term bond yields at or close to zero.

This means they have to move onto tertiary policy options, which necessarily includes fiscal and monetary policy coordination. There are various ways to do that that go along a spectrum in two main ways:

(i) Who gets the money (public sector, private sector, both) and

(ii) How indirect or direct the disbursement of the money is

The one thing that’s often overlooked

The influence of currency movements is frequently overlooked when looking at the overall mechanics of the situation. Many focus only on the trigger itself or whatever they read about in the media. For example, for the normal media consumer, they will look at the stock market rout as “coronavirus panic” and not directly realize the effects of the lost output and impact on the credit system.

Less appreciated are how movements in currencies influence the picture of what’s going on.

The first wave of the recent dollar move

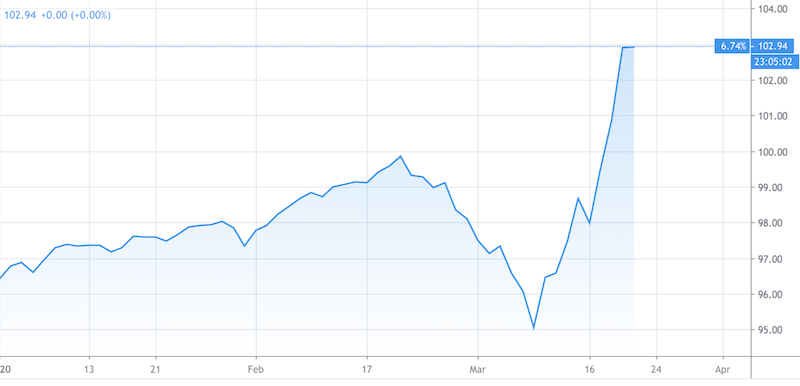

At the onset of the coronavirus hitting the markets, the dollar took a hit versus the currencies of other developed major markets.

(Source: Trading View)

This initial dollar devaluation was a product of the gains in the EUR and JPY.

The euro alone is worth more than half of the dollar index, DXY.

Dollar index components

Euro (EUR): 57.6% weight

Japanese yen (JPY): 13.6% weight

Pound sterling (GBP): 11.9% weight

Canadian dollar (CAD): 9.1% weight

Swedish krona (SEK): 4.2% weight

Swiss franc (CHF): 3.6% weight

The initial gains in the euro and yen primarily came from the unwinding of carry positions.

Traders looking to extract risk premiums from the market will often structure their trades by borrowing in a cheap currency and putting this into a higher yielding asset. For example, if a trader can borrow in yen at zero percent and put that into a stock they expect to yield them 6 percent per year, they capture that spread. If they leverage that, then even more.

In normal environments, carry trades tend to work well. But they’re like synthetic short gamma trades in the sense that when things are bad, they really fall apart. Years of gains can be blown apart in just a few weeks. That was true in March 2020 when the coronavirus effects really hit and in 2008.

The danger in such a carry trade is two-fold if the yen (or whatever cheap currency you’re borrowing in) is not your domestic currency:

(i) The currency could appreciate, which squeezes your returns, and effectively acts as an increase in interest rates.

(ii) The stock could decline, which squeezes your return in the other direction.

When people need to deleverage en masse – e.g., 2008 and March 2020 – the carry currency gets squeezed (e.g., euro, yen) as people unwind their short positions, which sends it higher, and risk assets decline because people need to raise cash.

The US still had positive interest rates at the front end of its curve going into the coronavirus crash at a little above 150bps. So the unwinding of carry positions mostly squeezed other developed market currencies that were cheaper to borrow in. When short positions were reduced in those currencies, that caused them to gain against the USD.

That was your first wave of currency movement seeing the dollar decline.

The second wave

Then the dollar bottomed because a new dynamic emerged.

Because of the economic damage caused by the coronavirus, a lot of entities globally have debts and obligations to pay and there’s a shortage of dollars relative to those figures.

In the US, corporations alone have an estimated losses in revenues of $4 trillion to $5 trillion so far. Going globally, that figure looks to be about $15 trillion. That’s about 20-25 percent of US GDP with respect to the US figure and 15-20 percent of world GDP pertaining to the latter figure.

Opening up of swap lines

The Federal Reserve opened up swap lines with five major developed market central banks (ECB, BOJ, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada). These swap lines are reciprocal and often referred to as the C-6 standing facility swap lines. They were first set up during the 2008 financial crisis.

That helps those jurisdictions get more dollars into their financial system through their banks. Central banks normally take care of money markets within their own borders by providing liquidity to banks to avoid funding stress.

But a lot of the world’s dollar funding occurs offshore outside of the Fed’s oversight.

In 2007 and 2008, the offshore dollar funding market became stressed due to the subprime lending market. BNP Paribas was the first notable example in August 2007 after the preceding years were characterized by the offshore dollar funding market being leveraged up. European banks also heavily acted to facilitate lending between emerging market countries (most notably China) and their need for USD funding.

When offshore dollar funding costs rose in 2007-08, European banks simply couldn’t get them from the ECB. There were US dollars as part of the FX reserves among the various national banks. But there was no reliable way of obtaining them and the quantity relative to the scale of the needs at the time would have been insufficient.

This brought about the idea of reciprocal swap lines between the US and other developed market central banks to help relieve some of this funding stress by getting access to the currency they need.

Due to the coronavirus and financial and economic fallout, these swap lines have been revived.

Meeting debts and obligation

Still, there are a lot of debts and obligations coming due for a lot of firms and there’s a shortage of dollars available to pay them due to hits in revenues.

Dollar demand is outstripping supply, so the dollar began to rise.

On top of that, the US federal government is having to spend a lot on programs to counter the steep drop in output.

To fund revenue shortfalls, that traditionally means having to sell a lot of bonds.

Who’s going to buy these bonds?

Lenders have been hit and the private sector doesn’t have the spare capacity to absorb it. That means the buying has to come from the Fed.

At the same time, the big supply of bonds having to come onto the market and the resulting supply/demand imbalance is being anticipated, or discounted into financial markets. That’s causing bond prices to fall (less attractive) and bond yields to go up. Prices move inversely to yields.

When you’re in a recession, as we can safely say we are now, letting nominal interest rates run higher than nominal growth rates is a bad idea. The Fed can’t let bond yields rise.

So, it’s either going to have to buy the bonds, or it’s going to have to provide the money directly to the Treasury and effectively monetize the debt.

If they let the bond yields go back up, then that’s a drag on asset prices. Higher yields reduce the prices of financial assets through the present value effect.

If they aren’t careful, or they’re too slow to react, then there’s going to be another wave of selling as credit spreads widen and debt squeezes continue.

Final Thoughts

The latest issue for the markets is the classic dollar squeeze that’s emblematic of a debt problem. You saw the same thing in 2008 as shown below in the shaded region.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

When a lot of entities globally have debts and other bills and there’s a low supply relative to the demand, then the dollar naturally goes up, holding all else equal.

The federal government’s upcoming big spending program is also causing a notable rise in yields. This is due to the surge in new bond issuance that’s expected to come out of it. This will ultimately total at least $2 trillion depending on their assessment of the damage and how the stimulus package is structured.

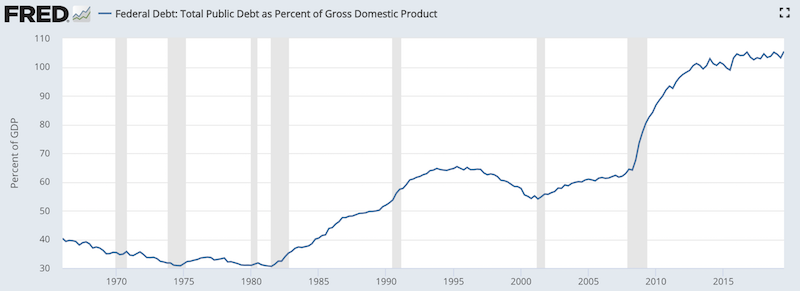

The federal debt as a percentage of GDP surged coming out of the last recession:

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Now it’s about to go up a lot higher unless the Federal Reserve directly creates the money and supplies it to the Treasury.

Otherwise, it’s going to have to sell bonds that could be upwards of 10 percent or even more of GDP. This is at a time where within 2-3 years, the US government debt rollover requirements were already looking at being around 25 percent of GDP.

Normally, you assume that can happen. But if you look at who the owners of that debt are and who the future owners of that debt are going to need to come from, a lot of it are non-US entities. In particular, they are countries like China who the US already has a lot of conflict with.

And then if you look at the yields on those bonds and the secular forces going against the dollar, as a foreigner, you probably don’t find the debt that very attractive.

The US is in the privileged position of having the world’s top reserve currency. Yet with the combination of the high debt situation, the obligations that are debt-like in nature and many multiples of that figure (i.e., pension obligations, healthcare obligations, and unfunded liabilities), the upcoming debt rollover required, and the fact that both the US private sector and foreigners won’t be able to absorb all that debt necessary to fund what it needs to fund, this is a secular problem for the currency.

The US dollar is currently being driven upward due to a squeeze, but this is temporary, particularly in relation to something with a hard backing like gold, which is no one’s liability and the supply of it increases by only a small amount each year.

When there’s a supply and demand imbalance through the issuance of debt, this normally raises interest rates. When this occurs you normally constrict credit. With the current crisis we’re in, the Federal Reserve can’t allow bond yields to go up when credit is already being choked off as lenders are pulling back and the central bank can’t stimulate much further due to zero interest rates.

Foreigners won’t be able to absorb all this debt. The motivations between domestic and foreign buyers of debt are different.

A foreigner buyer cares about the currency. If they’re getting a 1 percent nominal return on a bond, if left unhedged, just a one percentage point adverse move in the currency would wipe out the entirety of the annual yield of that bond. A domestic buyer cares about inflation to calculate the real return of the security – i.e., what’s the rate of inflation and how does that compare to the nominal return advertised on the bond. The difference is the real return, with the higher the real return the better. When the real return is lower, they’re more likely to look to something else, either riskier form of credit or stocks if the risk premium is good enough, or another safe haven asset like gold, which typically increases in value when the real interest rates on fiat money becomes unacceptably low.

Lacking support from foreign sources of demand, the Fed is going to have to come in to monetize the debt to avoid triggering an increase in interest rates, which is not at all in their interest, particularly now with the large output gap.

The US is in an advantageous position with its reserve currency status. But it risks endangering that with its finances long-term.

At the same time, when monetary policymakers have to choose between the two alternatives of what to do upon a big debt issuance – namely, taking it through the interest rate channel (i.e., higher interest rates) or through the currency channel (i.e., a secular pressure on the currency) – they’ll prefer to take it through the currency. This assumes that the debt is denominated in their own currency. (Reserve currency countries can borrow in their own currency; non-reserve currency emerging market typically borrow in a foreign currency, which makes the nature of their depressions inflationary in nature rather than the deflationary ones experienced in developed markets, but that’s an entirely different subject.)

The key thing for the Federal Reserve currently is to prevent interest rates from rising due to all this sudden unprecedented level of spending that needs to go on and needs to be financed in some way (bonds or directly monetized).

If they aren’t careful or they’re slow, then they’re going to get another wave of selling in financial assets as credit spreads widen and debt squeezes continue.