Demand Shock: What It Is & Why It’s Relevant to Markets

Demand shock refers to an unexpected demand event, which leads to a large and persistent increase in inflation (and potentially interest rates). Demand shocks can be caused by supply-side shocks (e.g., oil supply shocks), monetary policy actions (e.g., central bank rate hike or QE contraction) or people changing their spending habits (e.g., deciding to save more).

Demand shocks can cause sudden shifts in inflation expectations because of how they impact aggregate demand. This can cause wages and prices to adjust over time before central banks have a chance to adjust monetary policy.

Demand shocks are not something that central banks need to worry about during normal times – economic equilibrium ensures inflation remains low and stable. A demand shock is a concern for central bankers only when the economy falls out of equilibrium, which is often associated with demand-pull inflation.

Demand shocks are significant because they play an important role in determining how monetary policy is conducted in the short run (i.e., changing interest rates).

Demand shocks can be considered one of the most significant risks to global financial markets because they have implications for key economic indicators like GDP growth and inflation levels, both domestically and internationally.

This, in turn, flows into movements in asset prices that respond to shifts in discounted conditions.

Post-Covid Demand Shocks

The coordination of monetary policy and fiscal policy has created a self-reinforcing surge in demand that is making it harder, not easier, for supply to catch up.

Even as supply lags and higher inflation looks less and less transitory, markets are discounting that inflation will fall back to central bank targets. This would otherwise allow that monetary policy to remain easy for a very long time.

While the headlines tend to focus on the micro elements of the supply shock – for example, the Los Angeles port, Chinese coal and energy, European natural gas, semiconductors around the world, UK truckers, and so on – this largely misses the macroeconomic cause that’s more persistent and lacks any type of simple solution.

Inflation globally is largely not a pandemic-induced supply problem or mere pandemic-related volatility in supply.

As shown later in this article, supply of almost everything is at all-time highs.

This is mostly an upward demand shock created by the combination of both loose monetary and fiscal policy.

Some of the drivers of higher inflation have been transitory, but a lot of the supply/demand imbalance has been spreading, not getting better.

This matters for markets. A demand shock can impact markets in two main ways:

1. Demand shocks move inflation towards the higher end of central bank targets (i.e., hitting an upper limit or exceeding it).

As inflation increases, it requires tighter policy which often compresses equity valuations and raises credit spreads (or risk premiums for borrowers/risk-takers).

This is especially true if policy has to follow a path that is tighter than what had been previously discounted in.

2. Demand shocks undermine the operation of forward guidance, which is when central banks commit to holding interest rates lower than usual but find they’re limited because of a combination of:

a) inflation running too high

b) asset bubbles disrupting financial stability

This is why traders and investors care so much about whether the Fed is still committed to its 2 percent inflation target.

It also points to potential divergences in policy (e.g., between the US and Europe and other regions globally) that could cause relative currency movements.

For example, if one area needs to tighten policy relative to another, that’s likely to cause currency appreciation and more FX volatility. This is especially true if one area is tightening and another is easing, creating trending currency movements.

Demand shocks matter because they impact both short-term and long-term inflation.

They can also change expectations about future price growth, which then requires changes in central bank policy accordingly. Demand shocks represent an additional risk factor for global markets that is just another reason traders and investors care about supply/demand imbalances.

Why is policy more inflationary now?

The mechanics of combined loose monetary policy and fiscal stimulus are inherently inflationary: the combination of the two creates demand without creating offsetting supply.

The monetary-fiscal response that was seen in response to the pandemic more than compensated for the incomes lost to widespread shutdowns without making up for the supply that those incomes had been producing.

This is very different than the QE that followed the 2008 financial crisis.

By and large, in that case, QE was not combined with significant fiscal stimulus but instead worked by offsetting a credit contraction and, as a result, was not inflationary. The QE money that flowed into the system was essentially negating deflation.

The inflationary mechanics of the combined monetary and fiscal response started to play out once inventories had been drained in many things and enables market participants to observe just how strong of a tool it is.

The composition of the demand this policy mix fueled will evolve – such as a shift from goods back toward services as Covid recedes. But demand is likely to remain highly elevated.

There are still large cash balances sitting around – i.e., represents latent spending – due to the big effects that the monetary-fiscal response has had on the balance sheets of various entities.

Moreover, there’s the ongoing incentive being contributed by extremely low real yields and more fiscal stimulus is coming.

Getting demand lower would require central banks globally to shift toward more restrictive policies, which doesn’t look likely.

This article will look at the swell in demand and how supply is struggling to meet it virtually everywhere.

There is not enough of most everything – energy, raw materials, labor/workers, productive capacity, inventories, housing, and other goods.

And alleviating a shortage in one area is likely to make the problem worse somewhere else in the supply chain.

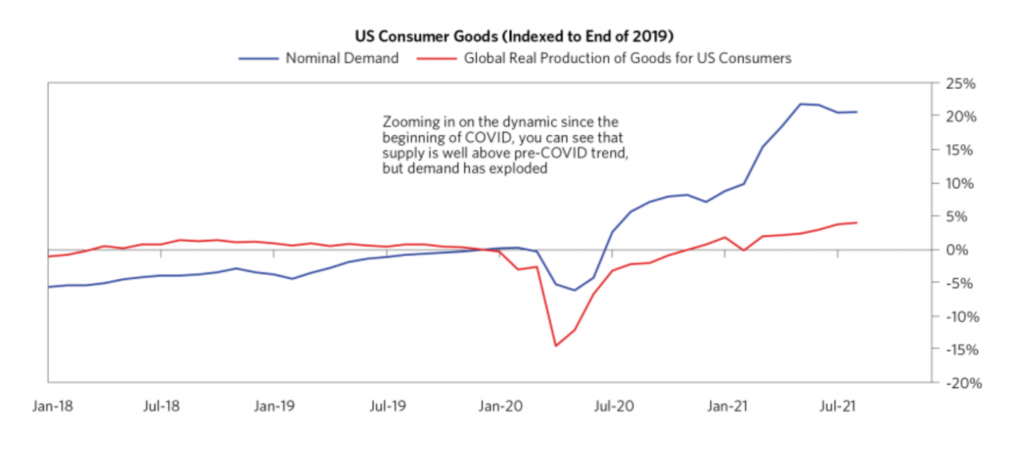

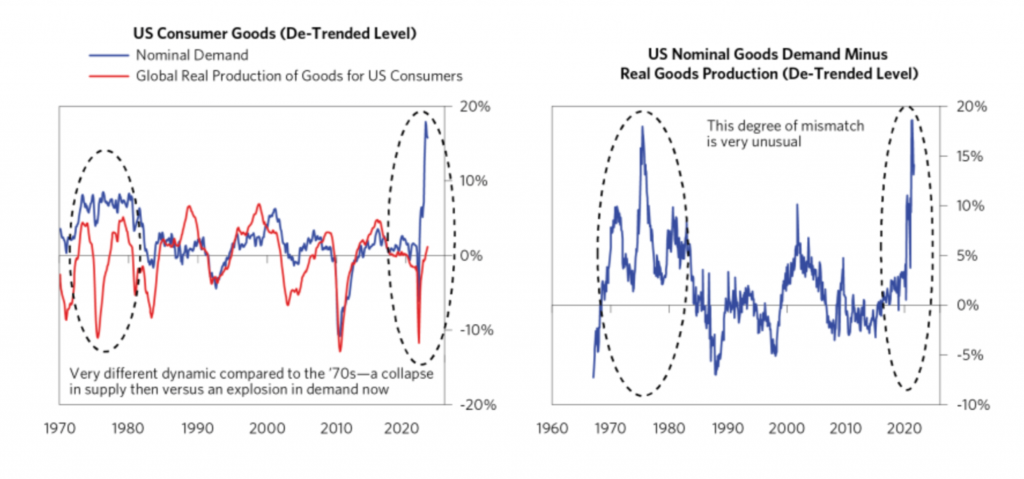

Goods Production Is Above-Trend, but Demand Has Exploded Higher

Supply recovered quickly in the post-Covid period.

In the first chart, real goods production was above its pre-Covid level by late-2020 and early-2021.

The issue is that demand has increased markedly, creating an imbalance of the two that hadn’t been seen since the 1970s. The chart on the bottom shows the current imbalance in a more zoomed out perspective going back decades.

What happened in the 1970s truly was a supply shock. In that case, supply collapsed (oil shocks were a big issue, which feeds into a very large chunk of production), and demand was up but more slightly. In the post-Covid era, demand surged, and supply is also growing, but it simply can’t keep pace with demand.

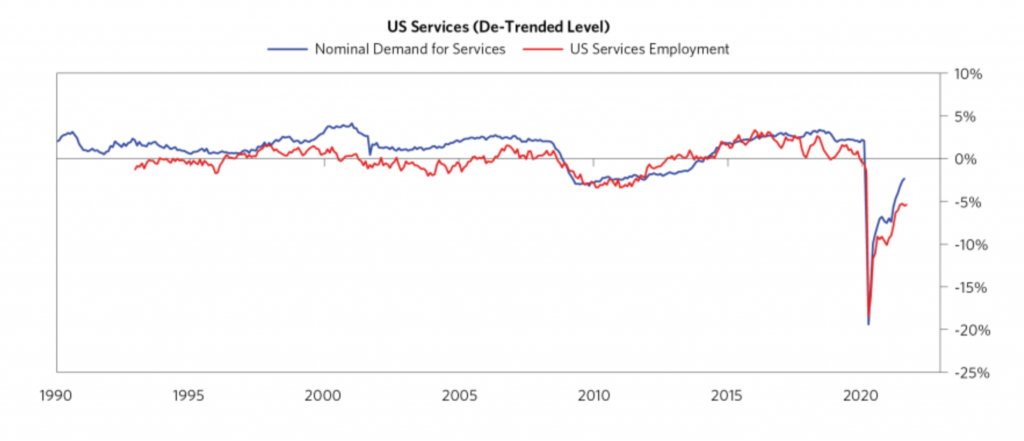

Some of the goods demand is unlikely to persist because Covid created the necessity for a lot of people to shift their spending to goods from services.

But the shortages for services is clearly visible and more persistent. Demand for services increased, but employers are having issues finding enough workers.

As services demand increases, this will put more pressure on a labor market that’s already suffering from worker shortages.

If you take how much labor it takes to satisfy services demand, if services demand goes back to pre-Covid levels it would bring unemployment down to historic lows.

This means wages will have to go up to get more workers to come back and work longer. It will also require more investment to improve productive output.

Given what’s causing all of this demand, addressing these shortages is difficult. You can address it in one place, but there’s no easy fix for everything.

It’s going to require a lot of extra investment and/or a lot of productivity enhancement in order to catch up.

On top of that, the gap is so large – and policy remains so easy such that it’s encouraging additional demand – that this gap is likely to be sustained going forward.

In terms of household demand, the combination of loose monetary policy and loose fiscal policy has created a lasting change. Governments transferred a large amount of cash to households, which for many more than offset all of the income lost due to Covid.

Household balance sheets are in a materially better state than they were pre-pandemic, as the policy mix created a significant amount of nominal wealth. This is very different from real wealth, but it pushed up the value of assets like houses, stocks, cryptocurrencies, and so forth.

And these gains have been broad-based, not just skewed toward high-earners or those with high net worth, which is different from QE policy.

Ongoing stimulative financial conditions have further lowered the cost of debt servicing. Incomes have also benefited as economies have reopened and people have gotten back to work.

In short, households are in better shape, have more cash, and are ready to spend. These conditions help with a self-reinforcing surge in demand.

Further in the article, we look at each set of shortages across the economy.

Each category has its own set of supply and demand conditions. But in all of them, demand is outpacing supply, even though supply is higher than what was seen pre-Covid.

As a consequence, prices are rising and are likely to continue to rise unless there’s:

a) a significant increase in productivity so supply will catch up with demand, or

b) policymakers move towarc a tighter stance in order to reduce demand in order to cure the issue of high inflation

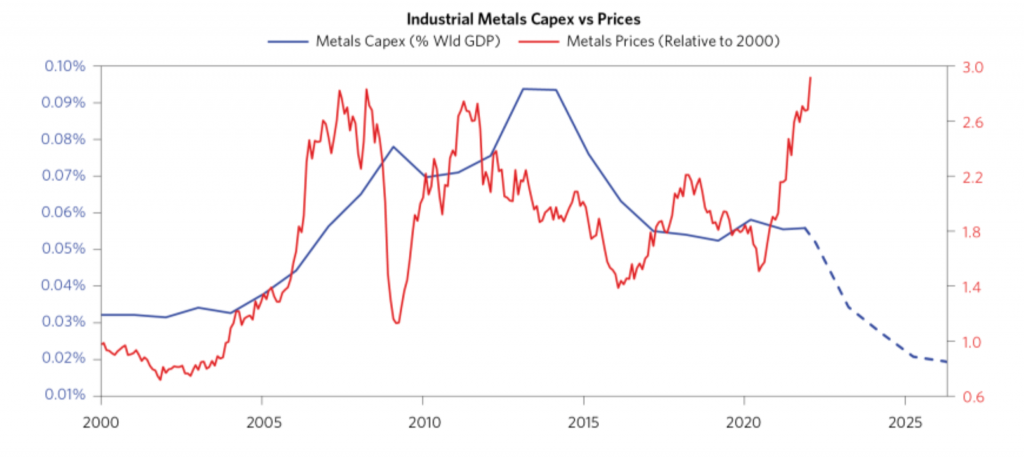

Raw materials are lacking

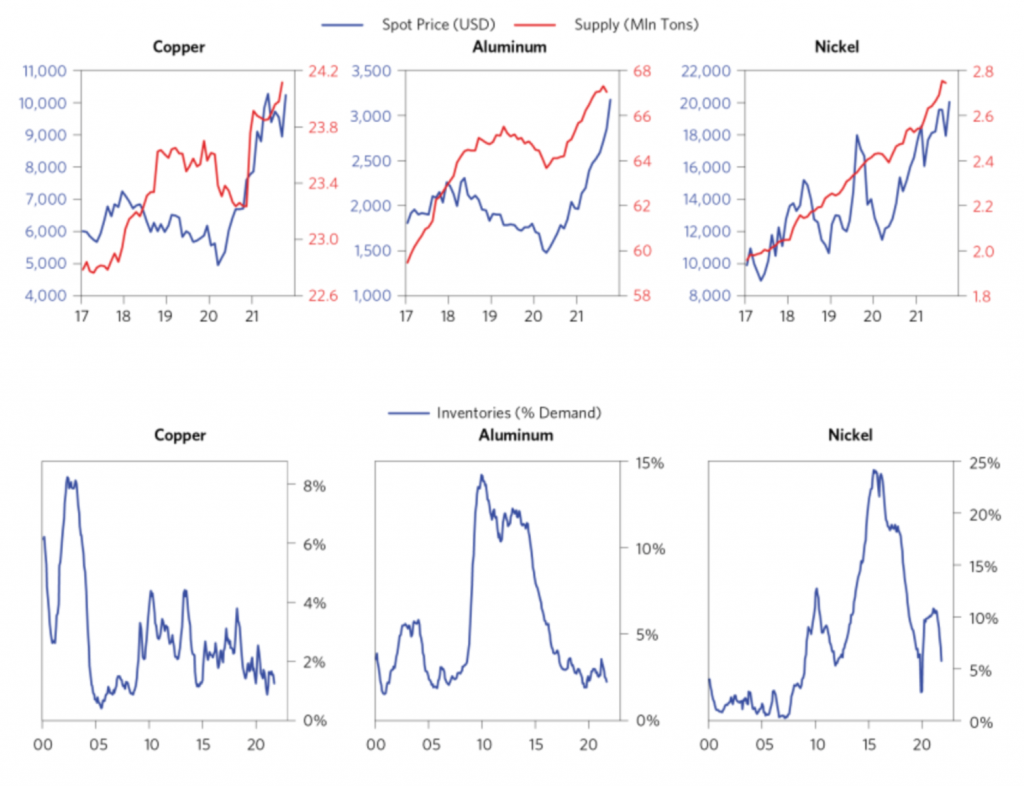

Metals prices rose a lot from 2020, as demand has simply risen way above supply.

Going forward, it will be hard to bring a lot of raw materials supply online because capex spending has been so low over the past decade. Moreover, capex spending on its own will be a strain on resources, particularly when companies have other issues to deal with, such as rising costs of labor and other things.

Capex still remains low even now that prices and demand for commodities are back to or above where they were before the pandemic. Some commodities are possible to ramp up quickly (US shale is a common example), but others it takes much longer.

This is because despite the seemingly strong incentive, it can take up to a decade to bring new supply online, so shortages are likely to persist.

Looking at examples of individual markets better paints the picture that price increases are not due to a shortage of supply, but due to demand.

For example, when it comes to copper, aluminum, and nickel, supply is much higher than in recent years. But prices are still rising and inventories are falling.

Energy

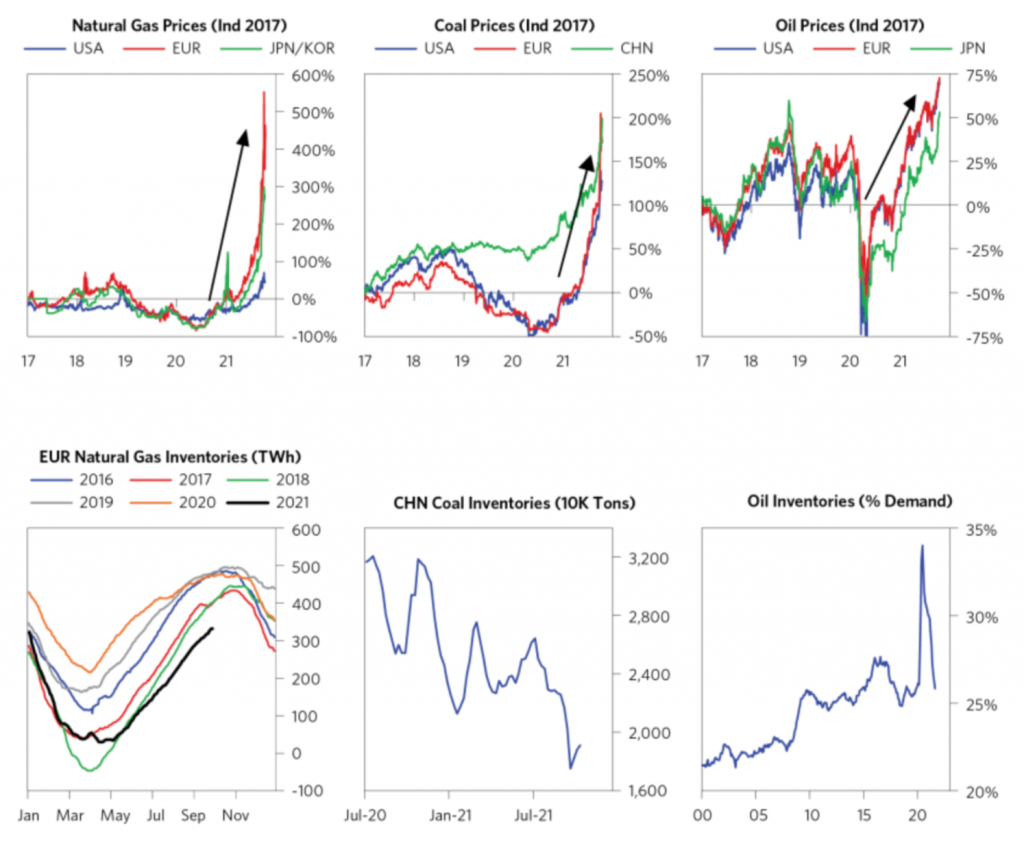

Likewise, there’s not enough energy to power economic activity given where demand is.

Prices of oil, natural gas, and coal are all going up. Even though commodities are heavily local markets, this is true globally.

There are also various types of idiosyncratic constraints on supply, such as environmental regulations constricting the production of coal or Russia restricting how much natural gas it exports to Europe.

But prices are rising because demand is surging, and that demand is depleting inventories despite production being high.

Climate initiatives have also reduced the supply of so-called brown energy. At the same time, infrastructure is still dependent on this type of energy. Accordingly, this is inflationary.

Productive Capacity

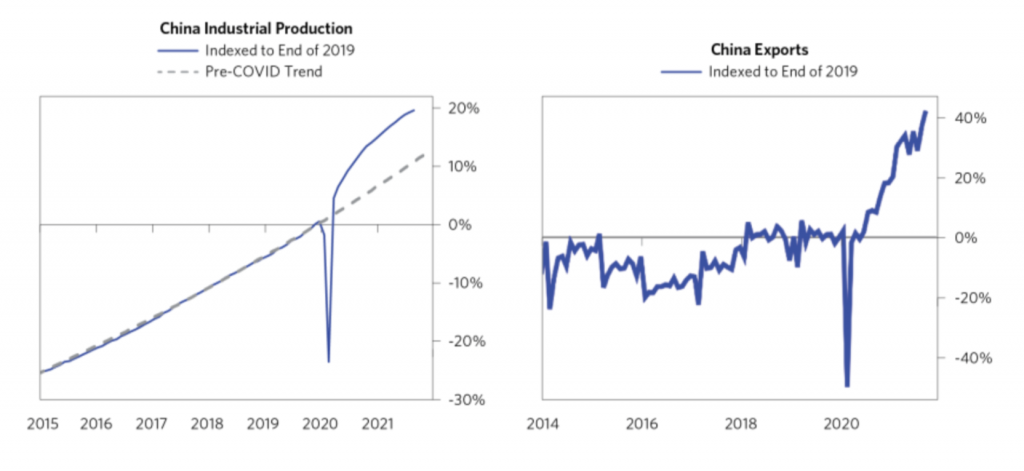

To keep up with the upward surge in demand, global production has risen above trend.

Most of the marginal productive capacity has come from China, which has ramped up its production (and exports) materially above where it was pre-Covid, but there’s a limit to how much it can improve further. Their production is up 20 percent and exports are up more than 40 percent.

China’s surge in production is also why there’s not enough coal or energy in China – huge global demand has created a massive need for energy.

Despite the big lift in supply, it’s not enough to keep pace with demand.

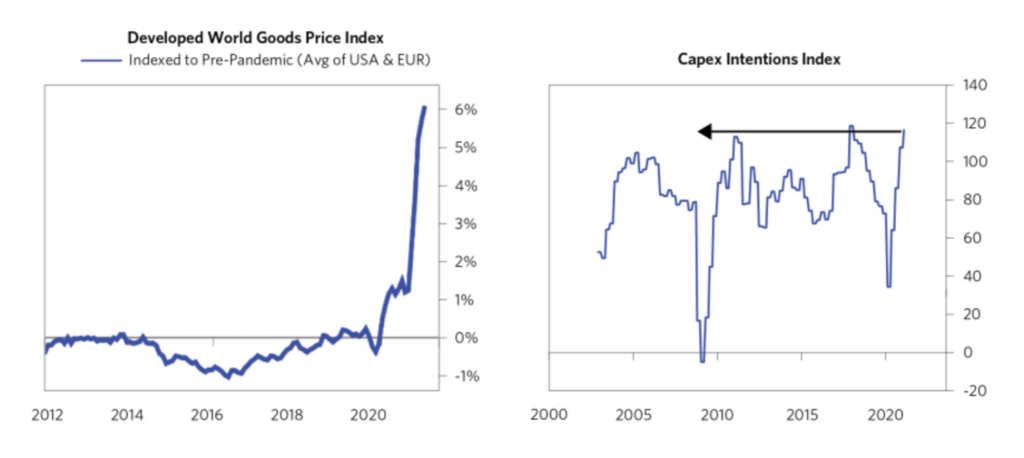

Consequently, developed world goods prices are moving higher because demand has pushed the global supply chain to a point where it simply can’t produce anymore.

As a result, businesses are pushing capex spending or intentions to highs in order to try to deal with the demand.

More capex will create more supply in the long term, but it also adds more demand that will contribute to the ongoing squeeze over the short run.

Shipping Capacity and Inventory

As you go up the supply chain you see more problems.

There wasn’t adequate production, and more companies don’t have enough inventory, which also forces adaptations.

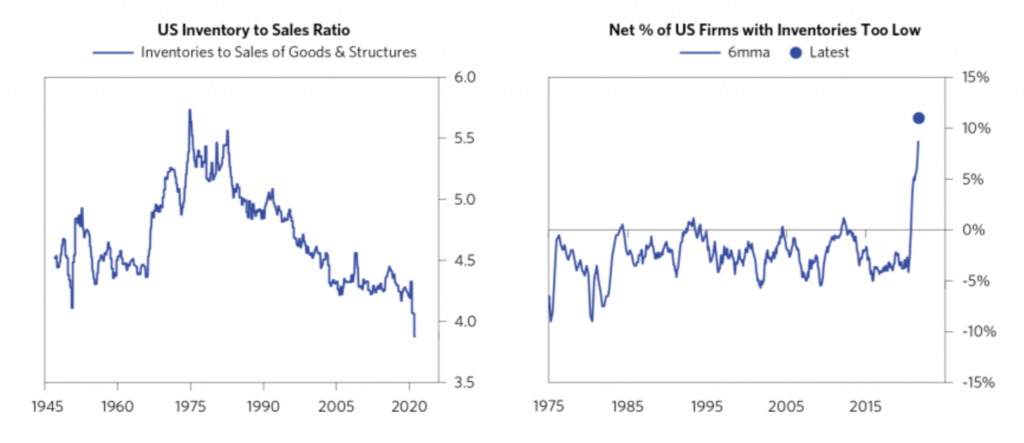

Firms have held low levels of inventory for decades to improve margins, and producers typically expect to be able to get their inputs and supplies quickly whenever they’re needed. But now that’s more challenging. Inventories across the economy have fallen to levels that haven’t been seen historically.

Based on surveys, the net percentage of US companies that think total inventories are too low is higher than anything that’s been seen since data started being collected in 1975.

Drawing on inventories was a way to provide enough supply to keep pace with strong demand in previous times. But companies don’t have that option now to satisfy demand on a forward-looking basis.

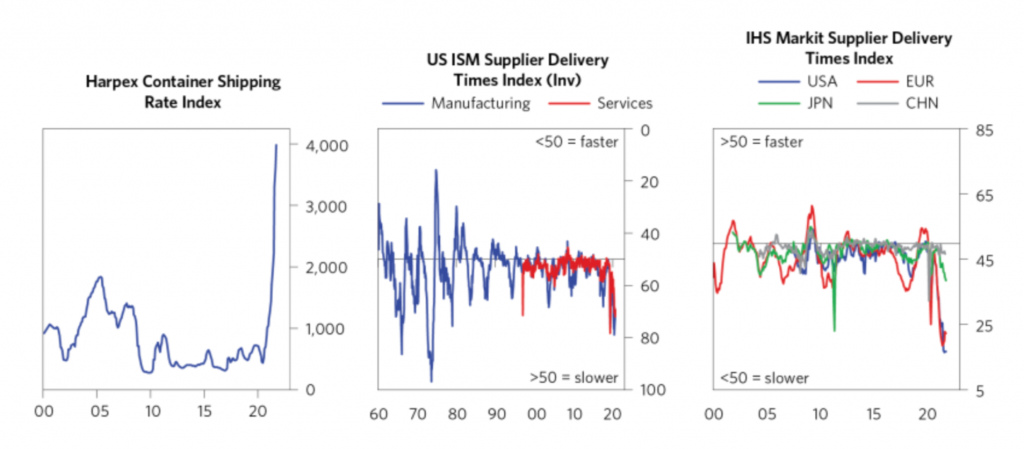

Not only are low inventories an issue, it’s harder for firms to get supplies delivered when they need them.

Shipping costs and shipping delivery times are much higher. This is true across a number of different metrics.

Housing

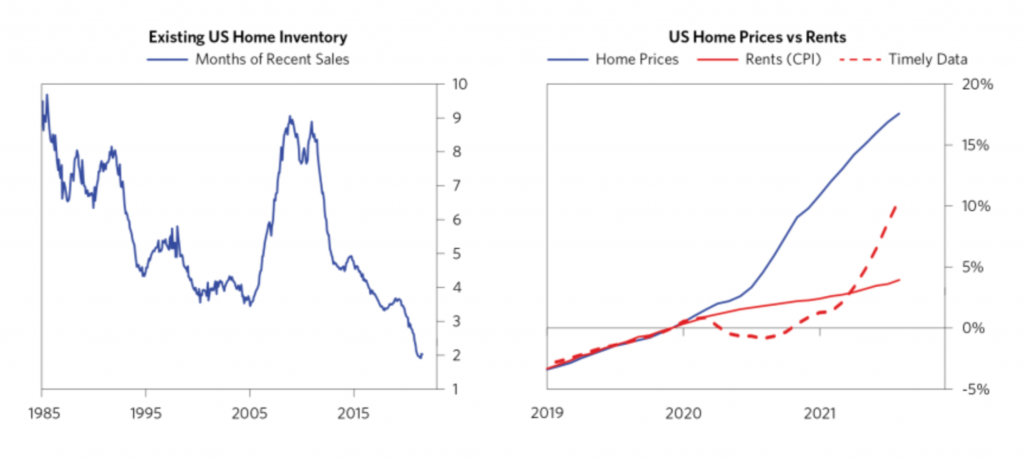

Housing is an example where inflation comes into awareness with a lag because of the idiosyncrasies in how CPI is reported.

In the US (and in many advanced countries), housing is about one-third of CPI. So it will be an important source of inflationary pressure moving forward.

Real interest rates are very low, which incentivizes more borrowing. (Naturally, because houses are so expensive, they are purchased with lots of debt.) And increasing wages having been sustaining an increase in housing prices, and supply just hasn’t been able to keep pace:

in the US, housing inventories have gone to levels far below anything seen in recent history. This is a remaining legacy of the 2008 financial crisis that saw building and construction fall in a big way.

As a result of these factors, home prices are seeing a sustained surge. Rents are also going up. But rents as reported in the CPI numbers are lagging this rise.

This will provide another support to CPI levels going forward.

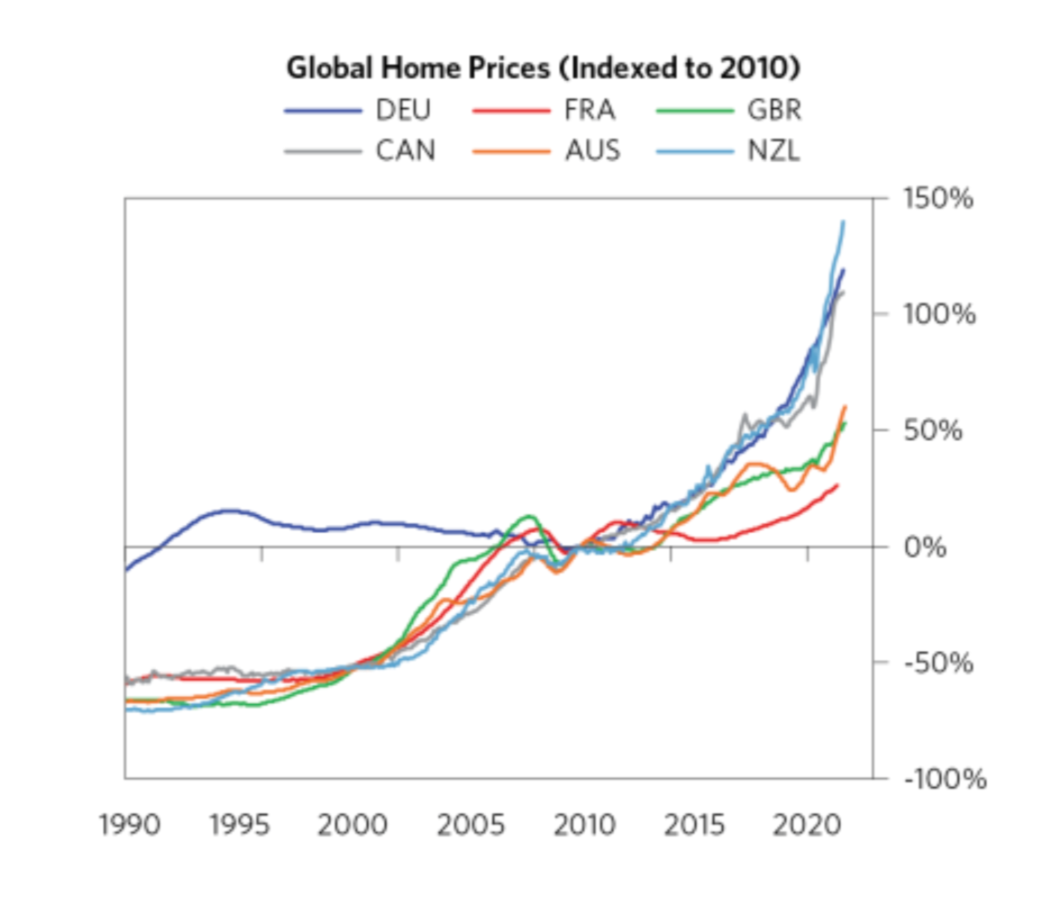

This isn’t only happening in just the US.

Typically, while there are macro forces that impact housing globally, but real estate is heavily a localized market, even within countries or regions within countries.

But there are fewer divergences across countries than normal.

This is because of the incentives created by the monetary-fiscal policy mix we’re in. We have extremely low nominal interest rates, negative real interest rates (nominal rate minus inflation), and a tight labor market that is pushing wages higher and getting more people into the housing markets.

Labor

And there’s labor.

We’ve spoken about the labor market in other articles and what’s driving the tightness of it.

This is different from what was seen in the 1990s, 2006-07, or in 2019 leading up to the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

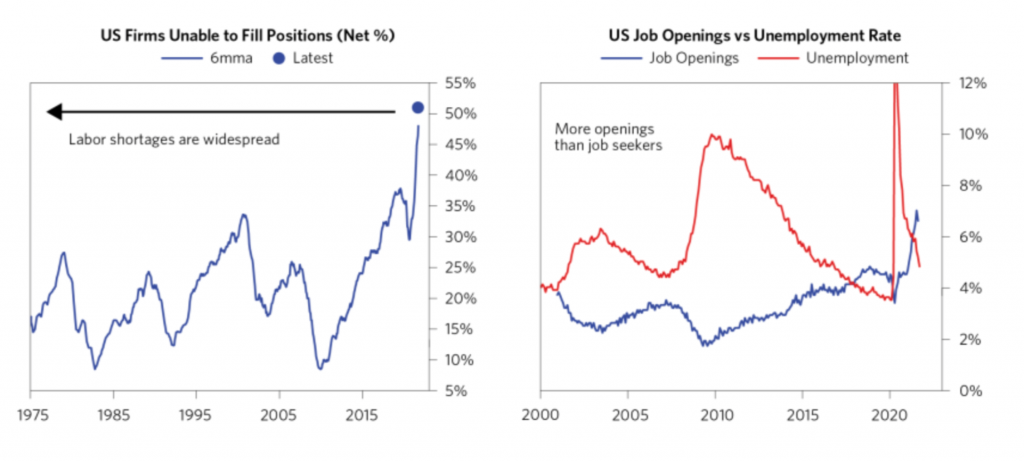

More than half of all companies in the US aren’t able to fill positions. Going back to data kept since 1975, it’s the highest ever. Ten to 30 percent is a more normal range.

There are more job openings than the total number of unemployed people, and this margin is significant.

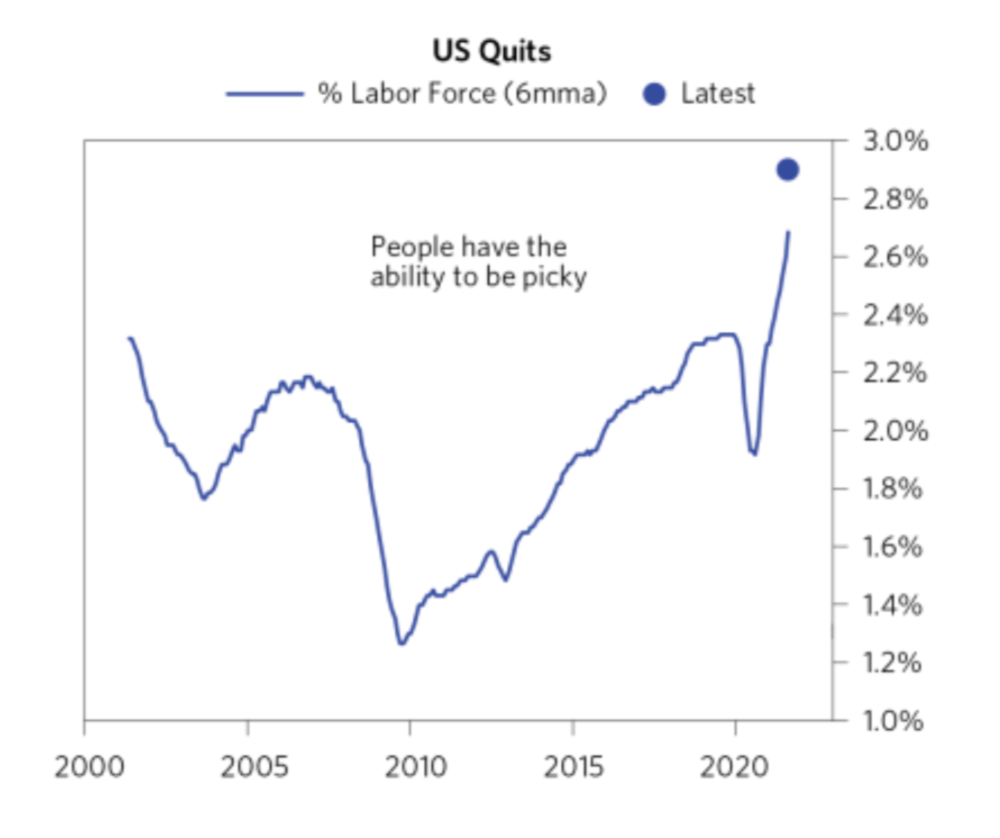

The quits rate – a metric of worker leverage – is the highest seen since data on the measure has been kept since the early 2000s.

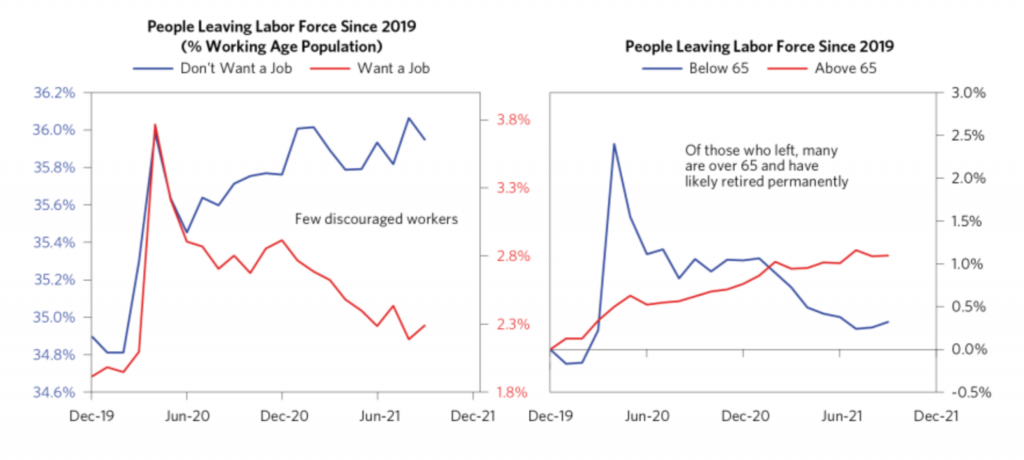

On top of this, those who left the labor force during Covid-19 aren’t as likely to return.

Many retired or retired early, in the case of age 60+ workers. Most say they don’t want a job. Many are turning to the gig economy or self-employment.

Many of these workers are going to need strong incentives to come back to the labor force. Basic pay raises aren’t likely to be adequate to reel them back in.

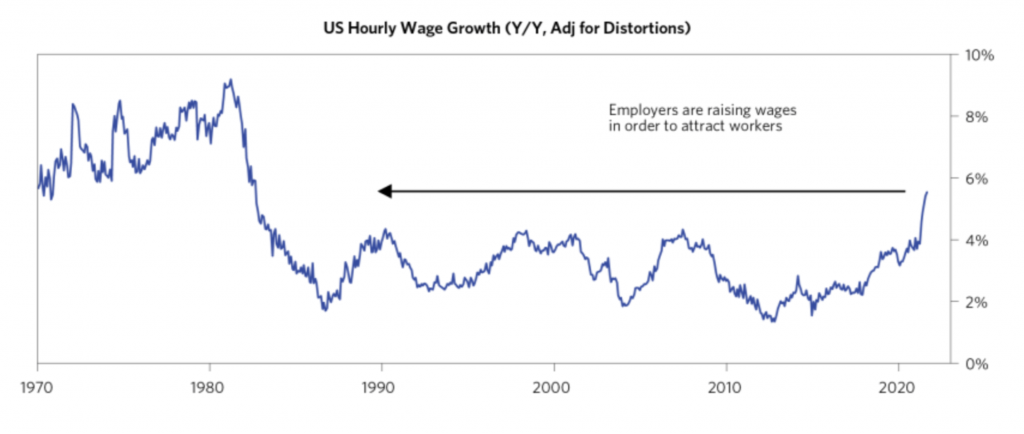

All of these factors are causing wages to rise at the fastest pace since the early 1980s. Like practically everything else, demand is exceeding supply when it comes to workers.

Wage increases and unemployment levels also come with a lag relative to other things. Labor markets normally bottom (i.e., unemployment rate highest) early in the following expansion after a recession (rather than during the recession itself).

If wage increases are due to enhanced productivity, that’s healthy and won’t necessarily flow through into inflation figures. It simply means more supply is being produced and incomes are increasing to reflect this.

But when there’s inflationary pressure due to demand exceeding supply, then that extra pricing pressure gets transmitted into goods and services and produces inflation.

For example, as consumers start spending down their savings rates in a way that begins to model the pre-Covid trends, that’ll increase pricing pressures as it pertains to services (which are labor-intensive). And the labor shortage will worsen further.

Higher inflation will start to get priced into future wage increases.

When that happens inflation becomes self-reinforcing. And there’s no simple way out of that.

Conclusion

Central banks have undershot inflation targets for years. In response, they implemented average inflation targeting regimes and zero rates while printing lots of money. In some places, this is going directly into the hands of households via fiscal spending, which is far different than pure QE policy.

It’s, in fact, a de facto (inflationary) monetization of deficits.

With demand outpacing supply virtually everywhere (raw materials, energy, production, housing, workers), policymakers are unlikely to be able fix shortages across all categories.

There are things they can do at the micro level. For example, they can open ports for longer (as they’ve tried in the US), or ease environmental regulations to increase production (as in China), but in order for supply and demand to match at levels that don’t lead to sustained price increases, there needs to be a large investment in productivity for supply to catch up with demand.

The gap between supply and demand is large enough that high inflation is likely to be sustained for some time and unlikely to make inflation transitory. This is particularly true given easy monetary policy in combination with easy fiscal policy is encouraging the creation of more demand rather than holding it back.

The asset price boom orchestrated by central bank policy is also reducing labor supply. Not only have retirements been surging, the Fed is talking of up to three million “excess retirements” in part because of higher asset prices. And without a surge in labor supply, inflation pressures seem unlikely to fully normalize.