How Coronavirus Impacts Business and the Fintech S Curve

The coronavirus pandemic and social distancing measures put in place to contain it have caused an unprecedented economic shock globally. Technological adoption rates (S-curve reshaping) have changed and the financial services industry will look different coming out of it.

The psychological aspect will also play a big part in why there won’t be a “V-shaped” – i.e., fast – economic recovery. Many behaviors won’t go back to normal. Moreover, central banks in developed markets, where most global economic activity occurs, are also “out of ammo”. The traditional methods of monetary stimulation have run their course.

The pandemic experience will be a defining event for many societal, business, and financial trends.

For financial services, much of the economic impact will be short-term. But one should expect that there will be far-reaching longer-term effects that will fundamentally reshape many aspects of the economy, business and work life, consumer preferences, and business behaviors and competitive dynamics.

The crisis has accelerated existing disruptive trends, such as the adoption of telemedicine, teleconferencing in areas with low penetration (e.g., educational settings), tele-banking, and a further accelerated push forward into e-commerce.

Higher risk populations, such as the elderly, are increasing turning to telemedicine in particular. Online education is seeing a boost and will continue for many schools and universities who are traditionally in-person institutions.

Many employees will want to continue their work from home arrangements, out of convenience or lingering concerns. Up to one-third of the US workforce can work entirely remotely. It will be more challenging for other workers.

Companies are likely to view remote work more positively. Some companies in high cost-of-living areas (e.g., Facebook) can also use it to help cut costs.

Assessing long-term effects

Identifying the long-lasting impacts of this experience will be paramount for financial market analysis.

Many of the longer-term ramifications are not yet known. Nonetheless, there are three main areas where there’s likely to be a lasting impact for financial service providers.

i) The resulting global economic recession will compel central banks to maintain zero, or negative interest rates for many more years. Interest rates are key for all financial assets as their prices are based on the discount rate at which future cash flows are calculated. Lower interest rates also lengthen the duration of financial assets, making them more sensitive to changes in rates.

Moreover, central banks will try to compel governments to increase fiscal stimulus with uncertain long-term consequences, and varying implications for banks and insurance companies who tend to struggle in super low interest environments. This includes a profit squeeze.

Low and negative rates are meant to help spur credit creation. But that’s unlikely to occur if bank profitability is impaired by low lending rates. This is why the US Federal Reserve is reluctant to push rates into negative territory.

ii) The pandemic will be a powerful catalyst for an accelerated migration to digital processes, and products and services by both consumers and businesses. Many of these processes that would have otherwise taken several years will take months.

iii) The Covid-19 crisis is accelerating a shift away from emphasizing the role of the shareholder toward addressing multiple stakeholders in business, such as employees and implications of the business for “broader society” (i.e., impact on communities, the environment, and so on). Increasingly, we’re likely to see a stronger social aspect to corporate strategy. The popularity of ESG fund flows emphasizes this trend.

Interest rates will remain very low, eroding profitability

The coronavirus and government action to reel in its spread have led to a severe contraction in economic activity.

Many corporations experienced near-complete losses in revenue, let alone profit. The deflationary effects of a reduction in aggregate demand, debt creation (especially at the sovereign level), and lower oil prices will keep interest rates very low for a long time.

The inability for monetary policymakers to stimulate their economies during the next crisis pre-virus was already a major concern.

Monetary policymakers have aggressively cut policy rates and phased in massive asset and credit support programs. This continues to push investors and speculators toward riskier assets in pursuit of returns. Both cash and safe government and corporate bonds yield virtually nothing in real and nominal terms.

The effects on commercial banks and other lenders are complex and there will be distributional effects depending on individual balance sheet qualities and structure.

Banks are suffering from deteriorating asset quality. Lending institutions that finance lending with core deposits rather than borrowing in wholesale markets will see their profits undermined by rock-bottom interest rates.

This is due to the fact that banks generally won’t pass negative interest rates onto their retail customers while at the same time lending rates will follow market trends downward. This diminishes the lending spread available and reduces net interest income.

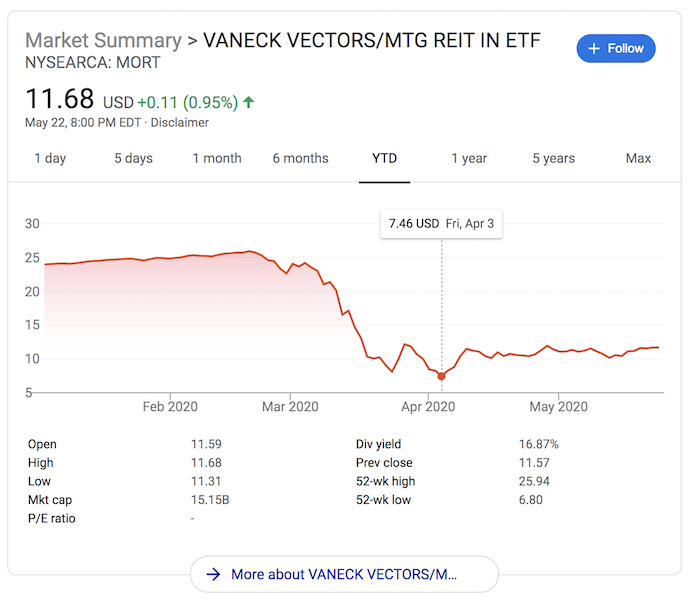

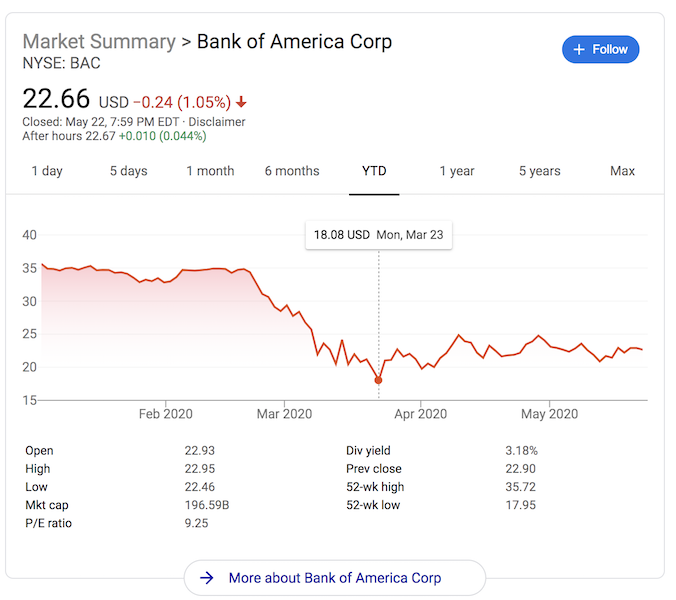

Other businesses based on the same “borrow short, lend long” approach have also gotten decimated. Many mortgage REITs lost over 75 percent of their value.

Spreads on bank lending will be constrained by low rates on government bonds. Banks particularly dependent on net interest income (NII), like Bank of America (BAC), were particularly beaten down. It lost half of its equity value in a few weeks.

For insurers, lower interest rates mean lower returns on traditional asset classes and a greater incentive to take risk or invest in less liquid asset classes.

The overall impact on interest rates on bank profitability – and hence ability to stimulate credit creation – will be higher in regions where the yield curve is likely to remain flat coming out of the crisis.

This is true in the euro zone and also in the US where interest on deposits is unlikely to go negative (and therefore not help widen lending spreads).

Potential winners

Easy money and credit policies also produce winners.

The US market is up 36 percent around two months from the bottom. Financial assets benefit more broadly. Providing money and credit into the financial system helps it get into assets and boost their prices.

Investors holding lower-grade corporate credit (i.e., junk bonds) are benefiting from the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank implementing programs that will allow them (the central banks) to buy collateral they otherwise normally wouldn’t touch. If a crisis gets bad enough, central banks will lower their standards of what types of assets they’re willing to buy.

Money market mutual funds are benefiting from inflows into investors looking for the safety and liquidity of short-term sovereign debt.

Generating winners through monetary policy

Because the two standard forms of monetary policy are virtually exhausted in developed markets – adjustment of short-term interest rates and asset buying to lower longer-term interest rates – the third form of monetary policy involves monetary and fiscal policy coordination.

There are a variety of ways in which this can be done. First who gets the money – the public sector, the private sector, or both. And how it’s disbursed – directly or indirectly, and through what forms.

This can mean something like debt monetization where the central bank retires debt directly, effectively “monetizing” the deficits.

The effect of these aggressive policies goes through the currency channel over the long-run. This would mean a weaker USD, holding all else equal. A weaker currency helps relieve stress on borrowers. When there is a lot of debt relative to income, as we have now, policymakers will invariably have to favor the debtors. This is particularly true when there’s a shock that impacts economic activity and the goal is to minimize the fallout quickly having imperfect information.

It could also mean something like “helicopter money” or a type of universal basic income (UBI). It can be unconditional (i.e., not tied to any spending, consumption, investing targets) or it can be tied to something to alter incentives or policy outcomes, such as specific investment accounts.

The central bank in the US is not legally permitted to send money to citizens directly. Congress can, but it involves going through a slow and partisan political process.

Helicopter money has the advantage of better targeting spenders and removing the constraints associated with the bond market.

More broadly helicopter money can be taken as any program of spending and consumption support without having it tied to borrowing. In other words, governments may need to break the linkage between spending and borrowing as it’s traditionally done.

In traditional monetary policy, short-term rates are policymakers’ constraining force.

When that can no longer be pushed lower, then central banks move onto buying bonds and/or other assets (quantitative easing). Then the bond market becomes the constraining force. Once policymakers are “out of room” with cash and bond yields at zero or a bit below, then they have to move onto something else.

In other words, central banks have to get around the bond market being the barrier to pushing more credit into the system.

That means moving on to a program such as the central bank capping the cost of capital. This would allow the government to borrow money, as needed, that can’t exceed beyond a certain yield (similar to yield curve control). Such a policy was deployed during the WWII era in the US. It’s used in Japan currently.

This is a type of function that can allow central banks to directly fund projects and government spending. Moreover, it effectively breaks the linkage between spending and borrowing.

Over the longer-term, this will lead to an increasing merger between monetary and fiscal policies. It will result in a policy framework that is largely independent of the bond markets. This can also be done without compromising the independence of the central bank, such that it’s not subject to the often short-term political goals of elected leaders and other bureaucrats.

Either way, such policies are designed to protect the economy from large-scale bankruptcies and to alleviate economic hardships.

Central bank actions have, to date, partially filled the substantial gap associated with reduced business and consumer activity.

But longer-term, these initiatives are not “free” and bring into question the long-term value of the main reserve currencies.

Investors need to consider what their alternatives are when cash and bonds in their domestic currency (bonds are a promise to deliver money over time) no longer provide much in return – e.g., land, precious metals, other real assets, stocks in the most disruptive companies.

Portfolio construction will continue to shift away from traditional large-scale holdings in cash and bonds.

The pandemic is creating a rethinking of traditional business habits and producing a mass-scale shift into digital technologies and services

The pandemic is producing a shift in business models and competitive dynamics.

Conducting more commercial services remotely and digitally was already a secular trend in the various ways in which it’s practical. Because of the pandemic, this trend has accelerated as a result of social restrictions and ongoing health concerns.

The pandemic experience has brought in a period of forced adaptation to living life digitally in all the ways possible. Those who can conduct business through digital interactions have, as a whole, had a big advantage over those who cannot.

Customers and businesses who were reluctant or otherwise slower to adopt digital technologies and service related to banking, payments, and commerce have effectively been forced to. Companies that haven’t engaged these services have typically seen a large drop in revenue.

White-collar workers have heavily adopted work from home practices. Its success, in many cases, will lead to new work habits.

Within financial services, social distancing requirements has created a surge in demand for contactless payments, e-commerce, and electronic cash transfers.

Financial institutions that lack this functionality will need to enhance their product offerings to accommodate this demand or lose customers who will get these services elsewhere.

It is both possible and probable that consumers who have adapted to new ways of shopping and working will maintain these habits once pandemic restrictions are lifted. Services businesses that have operated through the pandemic remotely and digitally may also realize that efficiencies and cost savings have come out of it (e.g., salaries and wages, rent, business travel).

A number of technologies now have a critical mass of adopters to allow for it to prosper and accelerate commercial adoption.

This includes digital collaboration (e.g., Slack), contactless payments and e-banking, online grocery, teleconferencing (e.g., Zoom), among others.

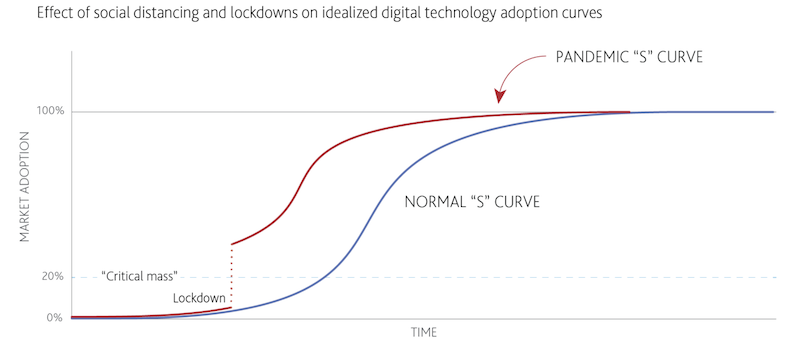

Technology adoption typically follows an S curve, referenced for its related shape. It starts off slowly before accelerating, if it ever does catch on.

This is true for various technologies, particularly those involving network effects.

For example, a social network is not very useful for the first adopters because few use it. More people began adopting Facebook when more people they knew signed up to it. Similarly, a telephone wasn’t very useful in 1900 when less than 10 percent of the US population had one.

More adopters help the S curve steepen earlier, potentially leading to accelerating growth going forward.

Social distancing has caused a surge of new users for some technologies

(Source: Moody’s Investor Services)

Financial services companies can benefit heavily from accelerating work from home trends. They have high expenses, and much of the work can be done remotely over a computer and through teleconferencing. The potential cost savings can be considerable.

Many large companies already outsource their middle and back office functions (e.g., IT, accounting) to lower cost cities such as Salt Lake City, Utah or to foreign countries with increasingly educated (but still cheap) workforces, such as India or the Philippines. Many investors will call on portfolio companies to slash labor expenses through this channel.

Companies that increasingly adopt permanent remote work and implement it successfully will enjoy more cost savings as this trend progresses. It will also help large financial institutions with a high brick-and-mortar presence to close the competitive gap with digital-only up-and-comers.

Moreover, during times of crisis, consumers might also prefer institutions that are more established brands relative to smaller companies, particularly for core banking activities (e.g., deposits, asset custody).

Risks to established financial institutions

At the same time, digital acceleration brings risks to established firms.

Google and PayPal are already well entrenched as established players for online business transactions. Venmo (owned by PayPal) and Apple Pay are convenient and universal as a form of contactless payments and will be difficult for established brands to copy.

Digital payments platforms like Zelle, owned by traditional commercial banks, are a good response to new fintech payment solutions, but likely not enough.

Fintechs also exist outside of traditional regulations, which is why “shadow banking” systems become so prominent and modern credit systems are so dynamic. Fintech firms have an advantage in the way they can reach those who lack banking solutions.

In particular, US fintechs are working with local and federal governments to get support payments and lending support to those without traditional banking services. Many are accepting loan applications running through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the most popular business “help fund” implemented by the US CARES Act in response to the Covid-19 crisis. They have also been less prone to criticism of their handling of PPP loan approval and disbursement – e.g., the speed at which the process moves along, size and prioritization of the companies who get the loans.

In the United Kingdom, fintech companies helped provide government-backed loans to small business. Established firms were criticized for not moving rapidly enough to disburse funds until the loans were fully government guaranteed.

The barriers to entry in the financial services sector are high, but many challengers could emerge from this crisis in a stronger competitive position relative to how they went in.

Effects on corporate and social behavior and corporate decision-making

The pandemic and economic hardship is increasing attention on corporate social behavior. The economic hardship has increased focus on the nascent trend of focusing on a broader stakeholder field.

Maximizing profit and shareholder returns is the typical way in which companies make decisions. It has never traditionally been that controversial, as successful companies and successful shareholders are normally an indication of customers getting value from the products and services they sell.

Following the “Friedman Doctrine” (1962):

There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.

However, there is more interest in recent years in including a wider range of stakeholders into corporate social responsibilities. Some argue the general economic idea behind the Friedman Doctrine is socially suboptimal or even morally wrong.

ESG investing has grown in popularity, with its focus on environmental, social, and governance factors.

Instead of shareholder focus, more emphasis is being placed on other stakeholders, including employees, communities, customers, society, and the environment. These ideas have caught on among some CEOs and well-known investors. Some have committed resources to the idea (e.g., Paul Tudor Jones’s “JUST Capital”).

Even going into the crisis, US politics have been more polarized than they have been historically. This is a social phenomenon that has roots in the economic environment, which Covid-19 has exacerbated. The US, and other developed countries, have the largest wealth gap since the 1930s. In terms of the distribution of asset ownership, the top 0.1 percent own as many assets as the bottom 90 percent combined.

This is heavily a function of central bank responses to debt crises – which were necessary – where low rates and asset buying (beginning in both 1932 and 2009 in the US, and now again) disproportionately benefit those who have them against those who don’t.

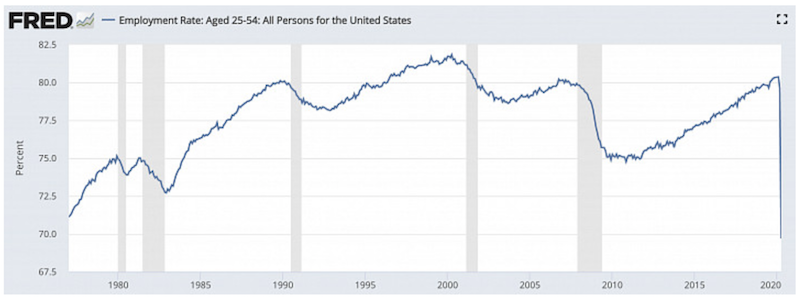

Today’s unemployment rate is the highest since the 1930s.

Moreover, indications are that there will be many furloughed workers left on the sidelines. Low-skilled workers are naturally the hardest hit – first ones to get laid off and the last ones brought back.

For one, about two-thirds of workers receive more being unemployed currently than they did at their jobs. $978 per week (average) in unemployment benefits translated into a monthly salary comes to about $4,200/mo. If that’s averaged over a 40-hour work week, that’s $24-$25 per hour. That’s higher than a lot of jobs.

If that level of unemployment benefits is kept up it could hamper effective labor allocation going forward. And like all crises, entities adapt and might find they don’t need to rehire a lot of furloughed employees.

Also, the employment ratio (employment divided by population for the selected age range) is the lowest it’s ever been.

The St. Louis Federal Reserve data goes back to 1977 – though even taking into account another dataset that goes back to the end of WWII – the current mark is still the lowest. It was 80.4 percent in February for the prime age contingent (ages 25 to 54), not far off the all-time high of 81.8 percent in April 2000.

(Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, St. Louis Fed)

The high structural employment from the sudden shifts in consumer behavior and long-term hits to many industries may continue to support calls for changes in corporate behavior.

Banks are likely to be a part of this sentiment. Traditionally, banks have been viewed as providing vital services to broader society as lenders and caretakers of savings and investments. Regulations, made in a prudent way, were made to balance out profit-seeking behavior with financial stability and greater social good. Increasingly, this balance is shifting toward the latter, and has been since the financial crisis in response to the belief that the financial sector is benefiting from an excessive share of rent-seeking.

We see matters like mortgage and other forms of loan relief, often due to political pressure. Financial institutions are the conduit by which public funding is flowing into the household and corporate sector as emergency response funding. Public authorities determine the criteria and how these loans are priced and managed. This reduces financial institutions’ ability to act in a traditionally commercial way.

Shareholder dividends and buybacks are also off the table for many banks in many countries irrespective of their profitability or balance sheet strength. Because of the social and political pressures, banks will be unlikely to act as freely in their own interests as before, and could be structurally less profitable in the years ahead.

Insurance companies

Some insurance companies are in a similar boat on the profitability front, and beyond purely just financial reasons, such as low interest rates. Some, because of social, political, and competitive pressures, are extending pandemic risk coverage beyond their contractual liability and refunding profit from expected lower loss rates back to clients.

Many insurance companies have been under pressure from certain governments to pay coronavirus-related claims that are not covered by existing policies (e.g., business interruption insurance). Moreover, many have been asked to accept delays in premium payments without canceling coverage and providing other forms of financial relief to customers.

Insurance companies are likely to respond by protecting itself against untenable demand through policy wording and means of exclusions. More insurance companies are likely to make voluntary ex gratia payments to appease customers. This will help maintain long-term relationships and avoid social and/or political and regulatory repercussions.

Going forward, insurance companies and governments are likely to set up public-private partnerships to establish pandemic-loss funds.

Some forms of this insurance already exist and are prized by some investors as a source of diversification – e.g., CAT (catastrophe) bonds – given their payouts are dependent on non-financial events.

Many governments globally have already transferred health, natural disaster, and retirement insurance coverage over to the insurance industry.

ESG going forward

Investors and asset managers are also keenly aware of the clients’ focus on corporate behavior and have increased their demand for ESG investments. While many focus heavily on the “E” component (environmental concerns), the social and governance components are increasingly scrutinized as well.

Regardless of one’s opinions on the merits of ESG mandates, large investors, including those of the largest equity and credit holding (e.g., sovereign wealth funds and pension funds), are increasing looking to implement ESG considerations within their portfolios. This affects investment flows, both passive and active.