Is China’s Stock Market Reliable – Or Should It Be Avoided?

China’s capital markets and their opening up to foreign investors is a big deal. No longer do market players need to heavily rely on just US and European markets for the bulk of their portfolio construction.

China has the second-largest economy in the world behind the US and is growing faster. It has the highest share of global trade. It is already the world’s leader in some technologies and expects to have a stronger military than the US relatively soon. Much of the world’s innovation in AI, quantum computing, data and information management, and other technologies comes out of China.

It’s expected to have a positive currency tailwind, which is important given investment in China means investments into the renminbi (aka the yuan, CNY, or RMB).

When investing into a stock or bond, your return is not just the capital gains and dividends and distributions, but also the returns achieved from the currency.

China’s currency is only around two percent of global FX reserves compared to nearly 60 percent for the US dollar. Given the economic differential between the two countries is no longer anywhere near that large, the currencies eventually will get closer in line.

The problems with China’s capital markets

China follows more of a top-down model to its economy. While China’s economy is largely market-based, it is heavily regulated by the state, such that their model could be closely called a form of “state capitalism”.

Their one-party government is referred to as the Communist Party, though China’s model is a far cry from the old Maoist, anti-capitalist system where there was little incentive to produce and there were no capital markets to help allocate resources.

When China cracked down on some of China’s most popular companies, such as Alibaba Group, Tencent Holdings, and Did Global, it caused their stocks to fall heavily.

It reaffirmed the distrust of many investors globally – i.e., as purported evidence that Chinese policymakers are autocratic and fostering an environment that’s not as hospitable to capital market development.

However, through the eyes of Xi Jinping and other policymakers, they view matters differently.

Technology firms can be boiled down into “essential” companies that China needs to have and “non-essential” companies that are good to have but not key to the country’s development.

Essential companies includes firms that make market-leading products in verticals such as:

- Semiconductors

- Commercial aircraft

- Telecommunications equipment

- AI and quantum computing

- Strategically important products that maintain China’s autonomy from foreign suppliers

“Nice to have” companies include those making strides in:

- Social media

- Consumer internet (e.g., gaming, private education)

- E-commerce

Consumer internet companies have seen a regulatory crackdown. But China will continue to support strategically important companies and ensure that its private sector does more to serve the Communist Party’s economic, social, and national security goals.

This will span various types of enforcement actions – finance, antitrust, social equality, and cybersecurity.

For example, Ant Group’s IPO was famously scuttled. Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion due to antitrust concerns.

After going public in New Yok, Didi Global was subject to a cybersecurity review. Education was turned into a not-for-profit industry.

Peer lending is regarded mostly favorably in Western countries, but viewed negatively in China to the point where it was “zeroed out” according to a Chinese banking regulator in December 2020 after a multi-year crackdown.

Tencent fell precipitously after Chinese authorities labeled gaming as “opium for the mind.”

China regulates what types of video games, movies, and books are released. Much of this is objectionable to Western observers.

For instance, most Americans and Europeans would not believe it appropriate for the government to regulate what types of video games children should play and believe those decisions should be made at the family level instead.

But this is rooted in cultural differences where China has more of a top-down system relative to Western societies.

This will have implications for investors in Chinese businesses.

And appealing primarily to the wants and desires of foreign investors, and those in its capital markets more generally, is not the Communist Party’s top priority.

To an extent, Beijing’s concerns on the tech industry align with those of Western governments, as it pertains to market power/monopoly, general influence in society, data privacy, and other issues. The Communist Party saw the tech sector’s rise as a challenge to its own power, influencing its regulatory response.

Is China fundamentally a good place to invest?

Events like Didi’s IPO and controls on its data usage and China’s education companies being decimated in a single administrative order (regarding their ability to make a profit) have created doubt about China’s true commitment to capitalism and the merits of its capital markets.

It’s especially confusing to those in Western markets who might view these measures as ostensibly showing their true colors as statist authoritarians.

However, over the past four decades, there’s been a clear trend toward developing a market-based economy and the commitment toward capital markets as a way to allocate resources.

Entrepreneurs have largely flourished under this system.

Even though Beijing takes a larger role in its economy in many ways relative to Western governments, those who have missed out on China’s ascent due to a lack of belief in their system or commitment to capital market development are likely to continue to miss out.

Data privacy is a concern for Beijing to the point where it delayed Didi’s listing and didn’t care if that knocked some value off the company.

The private education companies were turned into non-profits as part of China’s efforts to make these services broadly available and to avoid a type of inequality that can perpetuate (e.g., well-off families spending significantly more resources on their children’s educations than poor families).

The Communist Party believes these regulations are better for the whole even if it interferes with the interests of the individual stakeholders in these companies.

Is China really that different?

It’s also important to note that interventions that the US, developed Europe, and Japan are making in their own domestic markets are much larger than the interventions China is making in its own markets.

Because of the way developed markets are pressed against the zero interest rate barrier, this doesn’t allow central banks to lower interest rates much further as a means of changing the economics of borrowing and lending.

This has meant lots of quantitative easing (QE, or asset buying) in these markets as well as measures beyond these that involve coordinating monetary and fiscal policy.

China, on the other hand, didn’t need to lower interest rates to zero in 2008 or in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

There have been various other periods throughout China’s recent development that have caused investors to be skeptical. In August 2015, the renminbi plunged as the PBOC (China’s central bank) widened the CFETS band used to manage its currency.

Through China’s various hiccups over the past several decades, it’s managed the slumps skillfully.

The overarching in China has continually been the rapid development of capital markets (second in capitalization to only the US), openness to foreign direct investment, and support for entrepreneurship.

These trends are still fully intact even if there are tactical moves from time to time.

China’s state capitalism

China runs a type of economic system that is market-oriented with economic planning designed to achieve the Communist Party’s central goals of serving the interests of most people.

While capital markets have been and continue to be central to China’s development, policymakers do not allow any individual or company to be larger than the state itself.

Shareholders, entrepreneurs, and capitalists of all forms understand that their place in society is to serve the greater interests of society rather than pursuing their own in a way the state believes is sub-optimal for the whole.

In the US and most Western economies, it’s widely held that what’s best for the individual is best for the whole. People work to provide goods and services that provide value to other people, which gives them a commensurate level of income to then get what they want.

It’s a more bottom-up system as opposed to top-down. In China, those who don’t fall in line with what the state believes should be the proper way of operating suffer consequences.

For instance, in the US gaining a lot of wealth often goes hand in hand with gaining more power and having more influence to dictate government legislation and policy frameworks.

Large US corporations typically have lobbyists that help influence what legislation is passed and wealthy individuals often donate to political campaigns for the same reason.

In China, with its one-party system, having wealth does not mean using it to exert power over how things should go.

China is still figuring things out

China’s economic development has been extremely rapid. In the mid-1980s, nearly 90 percent of its population lived in poverty. This was still around 50 percent in 2000. Today, based on the official national poverty line, this figure is less than one percent.

As a result of its capital markets development, Chinese policymakers are still grappling over what the appropriate regulations should be.

When they are announced, they can come down quickly and aren’t well-understood, so there is often lots of confusion.

These are not anti-capitalist moves per se but rather a country trying to better modernize its regulatory framework and help achieve its goals of having a broadly prosperous society.

The influence of geopolitics

The US (and its Western allies) are increasingly in conflict with China in various types of ways.

There’s trade, economics and capital markets competition, technology, geopolitics, and military armament.

The US is changing its policies as it pertains to Chinese companies listing on US exchanges. (This is common throughout history when two countries are increasingly at odds with each other.)

There may also be limitations on US pension funds and the extent to which they can invest in China.

These are all things to be mindful of.

But what China is doing regulatorily should not be mistaken as strategic trend shifts where they’re moving away from a free-market system.

They will nonetheless run their form of capitalism differently from the way those in the US and most of Europe are accustomed to. China will not change its way to a Western-style capitalism in the same way it shouldn’t be expected that the US will adopt China’s unique ways of operating.

How does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine change things for China?

The biggest trend in emerging market capital flows in the past decade was a shift to China at the expense of every other country.

China had the world’s largest population, it had the track record of going from a poor country in the 1980s to a wealthier one today, it had an educated population, and all the ingredients to become a large superpower.

China has been the “it” economy for around 30 years, and this sentiment grew as China opened up to foreign investors.

But China is also seen as competitor to Western countries and one that’s likely to have a lot of geopolitical conflict with the US and other NATO countries.

It also tends to line up with Russia. They have similar styles of top-down governance and can help each other in various ways.

For example, Russia is a top nuclear power but is fairly weak geopolitically, technologically, economically, and doesn’t have strong capital markets.

On the other hand, China isn’t a top nuclear power but is stronger geopolitically and technologically, and has the world’s second-largest economy and capital markets.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and that natural partnership makes traders and investors warier of China.

Many investors are asking themselves why they invested in Russia in the first place. That question is also being asked about China too.

Russia and its stance on Ukraine is somewhat analogous to China’s stance on Taiwan. Both feel it’s a part of their sovereign territory. China is believed to be willing to fight over Taiwan in the same way Russia is willing to fight over Ukraine.

If Russia’s capital markets can be dismantled so swiftly and investment losses can happen so easily, that makes investors in China much more hesitant as well.

In periods of geopolitical conflict, liquidity can dry up and foreign investors may be shut out.

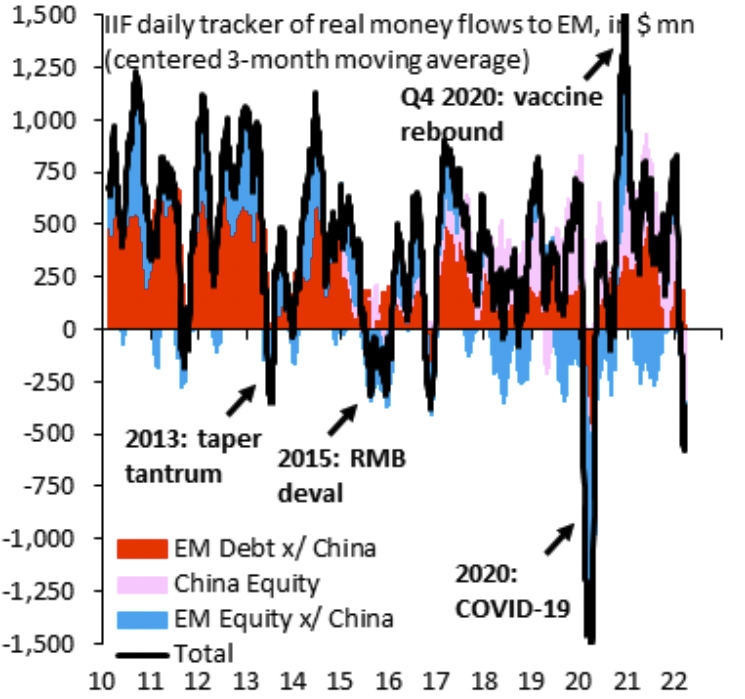

China (pink) is seeing big capital outflows, while the rest of emerging markets gets inflows. This never happened before on this scale and reflects asset managers looking at China in a different way after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

China capital outflows vs. inflow for other emerging markets

(Source: IIF)

China’s communication

Should China do a better job of communicating their moves to the public?

They absolutely could do a better job in this respect rather than making a move and leaving it to everyone to figure out what happened, why it happened, and what it means after the fact.

Western policymakers tend to do a better job of communicating their intentions publicly well before they happen (e.g., “forward guidance”). This helps keep markets steady and helps guide the public’s expectations over what the next several months or years could look like, especially as it pertains to monetary policy initiatives such as the path for interest rates and supplementary policy measures.

Chinese markets vs. Western markets

Both China and the traditional developed markets will continue to have opportunities and their own unique set of risks.

China is growing faster than developed markets but it has risks that are typical of emerging markets.

For example, China still lacks the trust of foreign investors, its regulatory environment is still in development, and its currency isn’t widely used.

Reserve currency status is one of the last things to develop and one of the last things to go among top global powers and empires.

With a greater decoupling between China and the West in various respects (e.g., supply chains, the development of various technologies), having exposure to both China and developed markets helps to complement and diversify a portfolio.

Both are viable places to invest. In a period of greater geopolitical competition and the large unknowns that accompany that, having bets on both horses is wise and important.

Most importantly, recent regulatory developments in China should not be misinterpreted as big inflection points that fundamentally alter the long-term attractiveness of China as a viable place to invest.

Attractions of the Chinese capital markets

As mentioned, China’s financial markets are now the second-largest in the world in terms of size and liquidity.

On its current faster pace, it can surpass the US as the largest economy in the world. This brings certain benefits in terms of global influence – e.g., technological sophistication, military power, and the increasing internationalization of its currency.

China also has some advantages over the main reserve currency countries:

1) Higher yields on safe assets (i.e., cash and bonds)

The yield on China’s 1-year bond (a type of cash rate) is much higher than the comparable rates in the US and Europe. This extends all the way out to 30-year maturities.

Based on that, we also know that:

2) China has a greater capacity to stimulate its domestic capital markets and economy

With more room to lower interest rates, this means China can get more out of its asset markets to stimulate its economy. In the US and Europe, because they’re pressed against their lower interest rate bounds, they have much less capacity in the traditional sense and will rely more on the less reliable fiscal policy.

3) Higher productivity growth rates

We know that China’s productivity rates are higher at about 3.0-3.5 percent growth annually versus around two percent or a bit less in the US and even lower in developed Europe and Japan.

A lot of China’s growth has been driven by credit. But because most of their debt is denominated in their own currency, this isn’t too much of a problem if it’s skillfully restructured over time (e.g., by lowering the rates, extending out the maturities, and/or changing whose balance it’s on).

4) China is focused on developing the top technologies

Europe’s capital markets have largely lagged behind the US markets in financial asset returns because it hasn’t participated in the tech revolution to anywhere near the same extent. All the main top tech companies – Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Facebook – are American.

Only around five percent of Europe’s market capitalization has been wrapped up in tech companies, compared with 25+ percent of the US market cap.

China is focused on developing its own technologies to ensure they’re benefiting the country first and foremost (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, AI chips, data and information management).

For instance, it restricts the operations of foreign firms, such as banning Facebook, Google, and YouTube outright.

Instead they’ve developed their own versions of these companies. Companies like Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba serve many of the same purposes.

The indebted, industrial-based “old economy” that characterized the interior Chinese provinces is slowly being replaced with the service- and tech-based “new economy” that characterizes the coastal portion.

5) China has an independent monetary policy and strong savings behavior

When a country doesn’t have an independent monetary policy, that’s a problem for market participants.

That means if they run into problems and their debt isn’t denominated in domstic currency, and they don’t have the ability or authority to rectify them, this can cause major issues for the country’s economy and for its asset markets.

Take the example of Greece when it had to come face to face with its debt problem in 2012.

Greece was pegged to the euro and therefore didn’t have autonomy over its monetary policy. That fell under the ECB and is one of the major downsides in joining a currency bloc.

If Greece had stayed on its old currency, the drachma, it would have simply devalued its currency and spread the effects externally.

Exports would have become cheaper internationally. This would have stimulated external demand for Greek products and services.

Being monetarily linked to everyone else in the EU, Greece didn’t have control over its situation and had to take the effects internally, with GDP decreasing some 40 percent.

It’s important to note that when a country devalues its currency, wages stay the same in domestic terms but change in relative terms to the external world. This can be good for exporters but causes the price of imports to go up and stoke inflation.

Devaluations can be dangerous and lead to bad inflation problems (e.g., Turkey, Argentina, or even worse episodes in history that have stimulated hyperinflation), but they are an easy way of getting out of a debt crisis when it is denominated in your own currency.

In cases where a country can control its monetary policy and undergoes a severe deleveraging, it can take usually about a decade to return to your previous level of economic output. (Each situation is different, but that’s where the term “lost decade” comes from.)

When a country doesn’t have an independent monetary policy, it can take quite a bit longer. In Greece’s case, it can take about 30 years.

In general, this type of pegged currency union makes Europe the most vulnerable of all developed market economies when there’s a contraction in output.

Many countries with dissimilar characteristics are tied together and individual countries largely lack the tools to combat their problems. On top of that, there is a lack of unity with and between countries, which can exacerbate the social and political divide and the desire to be civil and work together when there’s a downturn.

With matters like making private tutoring and education not-for-profit, China is aiming to prevent elements that can widen forms of inequality that can spark inequality and problems down the line.

And because China has a high savings rate relative to other markets, this makes investment returns less dependent on China’s economic growth rate.

This is because those savings can eventually serve the purpose of going into consumption or investment.

In a country like China, which just a generation or two ago was mired in widespread poverty (more than 85 percent of the population), many, particularly those who are now older, have never lost their cautiousness with money.

When a country becomes richer, the newer generation who was never immersed in these circumstances tends to be more willing to spend and indulge in extravagances.

Other parts of Asia that are largely considered “developed” with similarities to Western-style economies (e.g., South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong) may offer more stable markets.

But similar to their Western counterparts, they offer comparatively low returns, with cash rates (and many bond rates) in the 0-2 percent range.